The March 2017 parliamentary elections brought GERB back to power in a coalition with the United Patriots. This exotic coalition was the logical result of a patriotic turn, which became prominent at the end of 2015. The turn involved a change of focus in the political agenda of major actors from domestic matters related to the fight against corruption and judicial reform to geopolitical and security issues. Both GERB and the Patriots argued that the main problems facing Bulgaria are related to events in the Middle East, Turkey and Ukraine, and demonstrated little interest in the rule of law and anti-corruption issues.

The turn was helped by the rise of nationalistic populist movements all over the world in 2016: from Brexit and Marine Le Pen in Europe to the election of Donald Trump in the US. In Central Europe, the phenomenon is best exemplified by Orban in Hungary and PiS in Poland. Throughout 2016 Bulgaria was attuning itself to these fashionable trends, which resulted in the rise of actors instrumentalising nationalistic and populist rhetoric. On the wave of such public attitudes, general Rumen Radev was elected to the presidency. The picture became complete when the leaders of the main national-populist parties - Krasimir Karakachanov, Valeri Simeonov and Volen Siderov - found themselves in positions of power: the first two as deputy prime ministers in the Borissov 3.0 cabinet; the latter - an MP in the governing majority.

Selling this exotic coalition to the public and the EU partners was not an easy task. At the time when Bulgaria is bracing itself for the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU, the junior partner in the governing coalition is composed of parties, which have been openly and vocally anti-EU, anti-NATO and pro-Russia (mostly Ataka, but also VMRO and NFSB to a lesser extent). Moreover, in the final allocation of ministerial portfolios the leader of VMRO Mr. Karakachanov took over the important Ministry of Defense.

In order to make all these developments more palatable Boyko Borissov resorted to the following damage control strategy. First, it was (convincingly) argued that Bulgaria needs a government until the end of 2018, when the country's engagements related to the EU presidency will be over. The coalition between GERB and the self-styled patriots was the only one possible, since the BSP ruled out a "grand coalition". Further, the appointment of a special minister for the preparation for the presidency, Liliyana Pavlova, indicates that there will be at least a government reshuffle towards the end of 2018. In this sense, although the coalition with the Patriots was marketed as a four-year project, if things do not go well, there could be new elections in 2019 (together with the European Parliament elections).

Secondly, the coalition was based on a government program, which left out many of the policy commitments of the United Patriots. Most importantly, they abandoned their demands for a sharp rise in pensions and the minimum wage and agreed to the more restrained approach of GERB to the matter. In essence, GERB were quite successful in making their own electoral manifesto the backbone of the Borissov 3.0 government program, which is not that surprising given the fact that the parliamentary group of GERB is much larger.

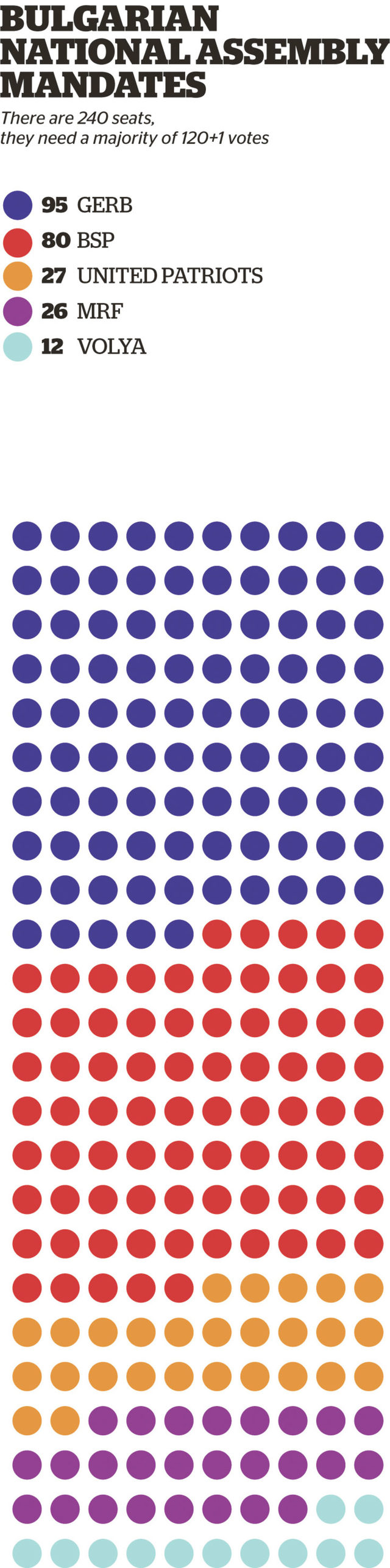

Furthermore, GERB and the Patriots agreed to disagree on all issues not included in the government program. This proviso opened the door to the Movement for Rights and Freedoms (DPS) to become the unofficial partner in the governing coalition. In substantive terms, DPS has no conflict with the major policies embedded in the government program. On all issues outside of it, GERB will be able to rely of the votes of DPS. This arrangement is essential because the majority of GERB and the Patriots is tiny and fragile - 122 of 240 seats in the National Assembly. With its 26 votes DPS provides more comfort to Borissov.

However, beyond pure mathematics, there are very important issues on which the government program is either silent or vague. These include the fate of formally abandoned Russia-sponsored energy projects like the Belene nuclear power plant and the South Stream gas pipeline. DPS will be key to building majorities on these matters, as well as to the continuation of the judicial reform, the setting up of a new anti-corruption agency and many others.

In short, as in the previous parliament, GERB has successfully smuggled DPS into government despite strong popular attitudes, according to which DPS is still in the grip of strong corporate interests.

Thirdly, Mr. Borissov was quick to grasp that a coalition with the Patriots will put him in a difficult position in Europe in 2017. The elections in Austria, the Netherlands and most significantly in France demonstrated that liberal Europe is rather strong and that the patriotic, nationalistic wave has probably already peaked. If in such circumstances Mr. Borissov has positioned himself in the camp of the Visegrad countries (which the patriotic turn would presuppose), he would have lost support from the core of the EU - Germany and France, in particular.

Therefore, his first steps in power were a strong reaffirmation of the pro-EU position of Bulgaria. For this purpose, after a few flamboyant TV interviews, the main speakers of the United Patriots were, if not silenced, then at least tempered and brought back within the rhetorical boundaries of the acceptable. More significantly, Mr. Borissov took part in an openly pro-EU high profile conference sponsored by the Party of European Socialists, where he declared that his government will work for a stronger Europe and will endorse further integration. During the same week, Mr. Borissov had meetings with French President Emmanuel Macron and German Chancellor Angela Merkel, where these messages were repeated. And finally, Mr. Borissov met with Turkey's President Recep Tayyip Erdogan, with improvement of the relationship between the EU and Turkey the main point of the meeting.

Thus, somewhat paradoxically, Borissov 3.0 will be a European patriot. The strong affirmation of the Euroatlantic orientation of the country is by all means a good news. It will be interesting to see to what extent the United Patriots will be playing along: no doubt their core supporters will be disappointed by the overall course of the government coalition. Another risk facing Borissov 3.0 is that the neglect of judicial reform and anti-corruption matters makes the government extremely vulnerable to corruption-related scandals, which are bound to occur. Such scandals anyhow continue to haunt the Supreme Judicial Council, the Prosecutor's Office and other elements of the judicial system. The KTB affair has also not seen conclusive resolution: no systematic account of the responsibility of key institutions for the bankruptcy of a major bank has been produced to date. Although the center-right parties peddling the anti-corruption agenda failed to clear the four-percent threshold to enter parliament, the citizenry is sensitive to these issues and the potential for public protests has not disappeared.

Borissov 3.0 is yet another demonstration of the affinity of the PM to balancing acts. This time the balls to be juggled are: the EU and patriotism; the rule of law and the existing agreements among powerful corporate interests.

This is a favorite act of a seasoned player.

Daniel Smilov is a Bulgarian comparative constitutional lawyer and political scientist. He is Program Director at the Centre for Liberal Strategies, Sofia, Recurrent Visiting Professor of Comparative Constitutional Law at the Central European University, Budapest, and Assistant Professor of Political Theory at the Political Science Department, University of Sofia.

The March 2017 parliamentary elections brought GERB back to power in a coalition with the United Patriots. This exotic coalition was the logical result of a patriotic turn, which became prominent at the end of 2015. The turn involved a change of focus in the political agenda of major actors from domestic matters related to the fight against corruption and judicial reform to geopolitical and security issues. Both GERB and the Patriots argued that the main problems facing Bulgaria are related to events in the Middle East, Turkey and Ukraine, and demonstrated little interest in the rule of law and anti-corruption issues.

The turn was helped by the rise of nationalistic populist movements all over the world in 2016: from Brexit and Marine Le Pen in Europe to the election of Donald Trump in the US. In Central Europe, the phenomenon is best exemplified by Orban in Hungary and PiS in Poland. Throughout 2016 Bulgaria was attuning itself to these fashionable trends, which resulted in the rise of actors instrumentalising nationalistic and populist rhetoric. On the wave of such public attitudes, general Rumen Radev was elected to the presidency. The picture became complete when the leaders of the main national-populist parties - Krasimir Karakachanov, Valeri Simeonov and Volen Siderov - found themselves in positions of power: the first two as deputy prime ministers in the Borissov 3.0 cabinet; the latter - an MP in the governing majority.