"The coronavirus map of Europe makes one thing clear: the richer nations of western Europe have suffered more from the virus than countries in the eastern half of the EU, almost without exceptions," The Guardian wrote in early May 2020. For once, Eastern Europe - the prodigal laggard son of the EU, seemed to be faring much better than the rest. Slovakia, the British media wrote, had recorded 20 times fewer deaths and one tenth of the infection rate of its neighbor Austria at the time.

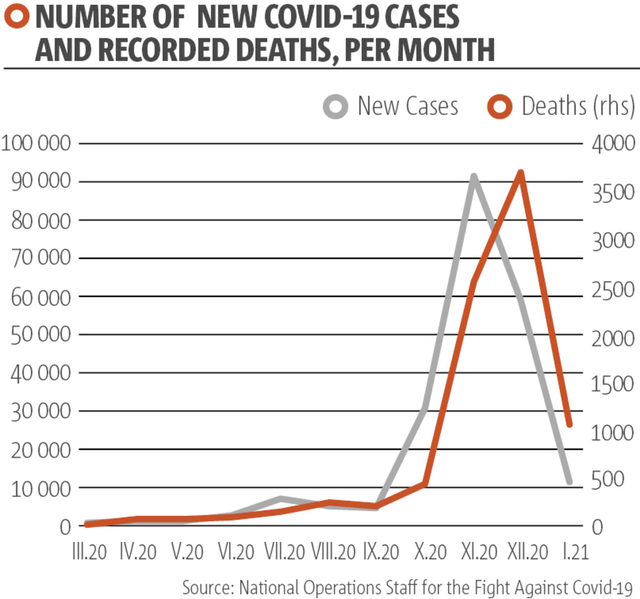

For three full months of the pandemic, Bulgaria had a total of 2,500 detected cases and only 140 recorded deaths.

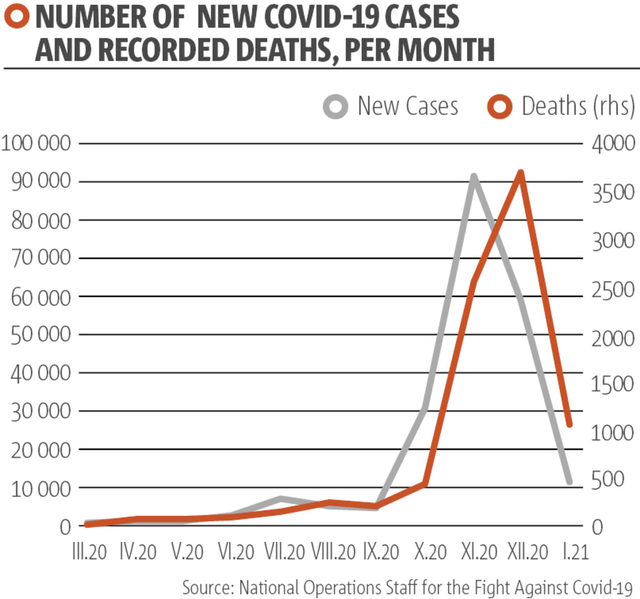

On 1 December, just six months later, the country recorded a staggering 221 deaths in a single day. A few days later, the National Statistics Institute (NSI) announced the deadliest month of its post-1989 history - almost 16,000 people have died in November alone, compared to just over 8,000 in 2019.

What had gone so wrong so quickly?

Early success goes to waste

While no single cause explained why poorer countries with worse healthcare systems and incomparable administrative capacities succeeded where their richer neighbors seemed to fail, several theories emerged. Some said that its relative disconnectedness from the rest of the world, and especially China, "saved" Eastern Europe. Others cited the lower population density, and thus limited infection rates, or noted that Eastern Europeans just did not live long enough to fall into the precarious group of over-80s, who were the primary victims of the disease in the West.But if there was one thing that happened everywhere and did not materialize in the West, it was the imposition of strict early lockdowns.

Bulgaria was no exception. Fearing that its understaffed, unreformed and underfunded medical system, employing predominantly aging doctors and nurses, would crumble under anything close to what happened to Northern Italy, the Bulgarian authorities - political and medical - urgently shut the country down for close to two months. At the time, the measures seemed draconian, and - some of them - illogical. Almost all merchants were closed, intercity travel was banned and even parks were off limits. The lockdown was imperfect and annoyed many, but the results were clear.

In a way, Bulgaria might have become the victim of its own success from springtime.

Pandemic weariness

Many Bulgarians grew indignant with all the seemingly unnecessary complications associated with the first lockdown, especially since the casualty and sickness rate from Covid seemed low. While transferring education online might have limited exposure of hundreds of thousands of people to the virus from March through June, it also meant that many parents had to stay home. Additionally, working people had spent their holiday time during the first closure and a second one would have caused additional problems to both them and their employers.

The stable summer infection rate during which life returned to something like normal also lowered the guard of the general public. The southern Bulgarian seaside, down from Burgas, had never had such a successful season, with small-scale, family-owned hotels and restaurants benefiting from the obstacles that stopped thousands from travelling to Greece, for example.

The daily protests in central Sofia that brought together up to tens of thousands of people also did not seem to make a dent in the Covid-19 statistics for the country's capital. The numbers of positive cases at the time for the 1,5 million city were similar to those recorded in much smaller municipalities.

Very few people noticed that, by 14 August, hospitals in some cities - most notoriously in Dobrich, Vidin and Blagoevgrad - were starting to struggle with the influx of patients. Overworked doctors' concerns about potential overwhelming pressure on the healthcare system were overlooked when the new school year started on 15 September. Unfortunately, many teachers would become the first victims of that ill-advised opening just a few weeks later.

Borissov's Achilles heel

Despite the frightening numbers and frontline doctors' pleas, the dazed authorities rejected a renewed lockdown akin to the previous March. "People are against it; we need to save their psychological health and need not worry them with a single measure," Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said in the last days of November, just as the experts and medics from his National Crisis Staff were suggesting at least a partial closure of schools, shops and restaurants before Christmas.This reaction needs to be put in perspective. The past year had been rough for the Borissov government even before the pandemic. But the situation got out of hand in the first days of July when mass protests erupted in the capital, calling for his and the Prosecutor General's resignation and early elections. The authorities entered panic mode, announcing a package of close to 1 billion euro in Covid-support measures in order to mitigate the growing discontent. But most of the money was not targeted where it should have been - at the struggling medical system.

The government slumbered through the summer and failed to implement basic reforms to the ailing healthcare sector until hospital beds started filling up at alarming rates. Panic arose when - notoriously - a couple of people died on the doorsteps of doctors' cabinets in November, leaving a sense of foreboding that what had happened in Italy in February might repeat itself in Bulgaria - but without the luxuries of Italy's stable medical system.

The second lockdown

Reportedly, at several points in the autumn, health officials urged Borissov to consider a new lockdown, but he refused. Finally, prompted by the worsening situation, the government acted.

According to data, 7,700 more people died in November 2020 compared to the average number of deaths occurring in the same month of the previous five years. While officially only 2756 of the deaths were of people diagnosed with Covid-19, clearly something had gone terribly wrong with the handling of the pandemic between May and December. Additionally, testing at the time showed that consistently over 40% of the people tested were infectious, and that is with extremely low testing rates.

At one point in December, Bulgaria was leading the EU in deaths per 100 000 people and was at the top for new infections.

The new lockdown was announced on 27 November and is supposed to last until 31 January. It does not, however, cover a lot of retail, hotels, or even pet stores. Nonetheless, COVID-19 numbers have been going down in the last several weeks, showing the effects of the new measures. Now all hope will turn to vaccines.

Vaccination laggard

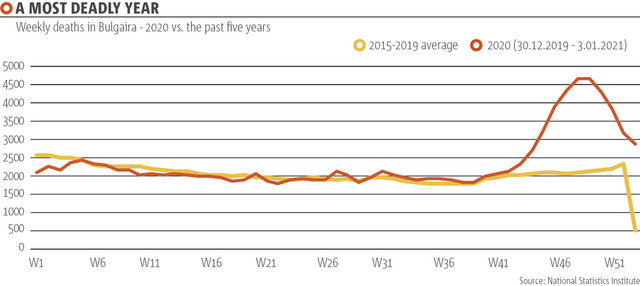

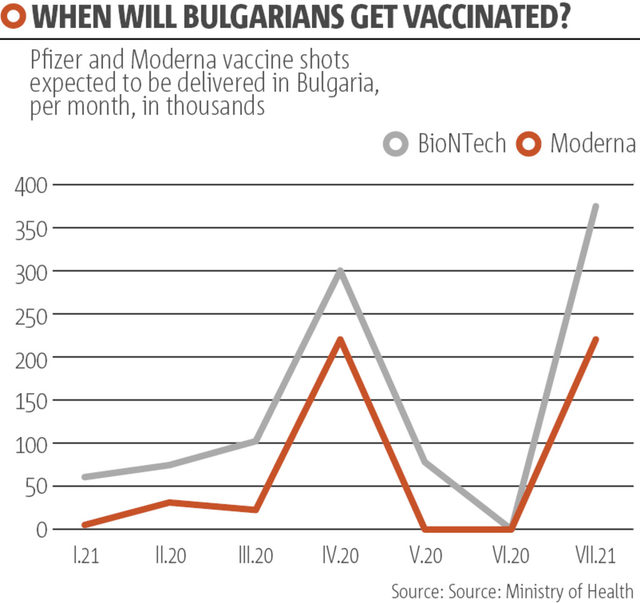

According to the vaccination plan of the Health Ministry, by the end of January the country should have received enough shots for the vaccination of 38,000 people; by the end of February it should get enough shots for 54,000 people, 322,000 shots for March. That means that, by the end of the first quarter of the year, 400,000 people should be vaccinated. Priority would be given to medical workers, residents and workers in care homes for the elderly, teachers and members of the state administration considered frontline workers.

Up to 13 January, 15,780 Bulgarians had been vaccinated according to the pandemic response staff, with an average of 1,600 people vaccinated daily with the 35,000 Pfizer shots available for 17,500 people (predominantly medics). On the same day, while welcoming the first batch of 2,000 Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, Bulgarian health minister Kostadin Angelov announced that the country had taken part in the second order of Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines, booking 2,9 million additional doses from it. This announcement came after criticism that Sofia was a "frugal laggard" when it comes to ordering flu shots, with the government having ordered only 9 million of the cheaper AstraZeneca vaccines that are still not approved by EU regulators.

In comparison, Denmark with a similar population, has ordered a total of 25 million doses of the vaccine, including six million Moderna shots, which are currently approved by the EU. It is unclear when the additional Pfizer-BioNTech vaccines would be made available, but the first order is supposed to be delivered by September, which probably means that the second batch will come later, likely pushing mass vaccination back until 2022.

Apart from potentially putting more lives on the line and jeopardizing the smooth electoral process that ought to take place somewhere between March and May, the slow vaccination process may impact the economic recovery. "Luckily," only a quarter of Bulgarians want the vaccine, so at least queues will not be long. According to another Trend agency study, 45 percent of Bulgarians say they will not vaccinate when flu shots become readily available and only 26 percent clearly state they will. While these results are not as bad as those of Poland, it still shows the alarming success of conspiracy theories and misinformation.

The way Bulgarian authorities treated vaccination did not help to alleviate skepticism at all. Notoriously, the first batch of flu shots arrived in Plovdiv, Bulgaria's second city, in hot-dog trucks, with the news reaching the New York Times. They were then kept in Soviet-made refrigerators that were over 40 years old, national TV channels broadcasting the whole process live. Funny reactions aside, it turned out that a state-owned company that had produced vaccines uncertified and had forged documents to export them to Turkey was responsible for the logistics of the important process. Even if all requirements for keeping the vaccine under the needed conditions were actually satisfied, as the company argued, the message that was sent to the public was plain wrong.

If the deliveries of all five pre-ordered vaccines happen as planned, there will be vaccines for 1,8 million more people - elderly and chronically ill - by July. There are two issues that put this plan to the test. Firstly, will the state be able to organize the vaccination of up to 45,000 people a day if it wants to reach the 70 percent of population immunization rate by the end of the year? The second issue is not domestic but rather boils down to the ability of the pharmaceutical companies to produce and deliver the promised quantities of vaccines on time.

No manpower

First of all, there were not enough doctors and nurses, despite the high number of intensive care beds advertised by the authorities (46,000). In total, there are about 19,000 doctors practicing in hospitals and just as many nurses - when at least 4-5 times more are required. Secondly, almost two thirds of them are over the age of 51, which automatically puts them in the high-risk bracket.

The number of doctors was deemed insufficient during a "normal" day, let alone during an outburst of a highly infectious disease. Add to that the number of doctors who got sick - over 5,000 in total - and compare it to the constantly rising number of people they had to take care of, and one can start to see how the crisis worsened in October-November.

The lack of personnel created heroic stories of elderly medics like 77-year-old Borislav Ivanov from Vidin and 81-year-old Maria Bogoeva from Dupnitsa, who volunteered to go back to work. These stories were inspirational, but also dramatic - they were doing it because there was literally nobody else left - the already overstretched doctors could not be transferred around the country to deal with needs in specific regions. "They would have closed my ward; in the name of my work collective I decided to come and save it," Doctor Bogoeva told Nova TV in December. In the case of Doctor Ivanov, the outcome was fatal.

No protocol

At the same time, the authorities failed to establish a clear protocol of how hospitals and doctors should work during the emergency. Until the very last moment it was unclear whether all hospitals ought to create Covid-wards, or if some specific hospitals would be transformed to only treat Covid-19 patients.

The already sparse number of paramedics and ambulances that had to transport people with complications (only 20 in total for Sofia) at times did not know where to take the seriously ill, because hospital after hospital told them that they had no spaces or refused to take more Covid-19 patients. The lack of a centralized system cost many lives, including those of younger people, whose families lamented publically how mismanagement had robbed them of their loved ones.

Proper treatment was not promised even to those who made it to hospitals, as they would likely get treated by non-specialists in infectious diseases who had to requalify quickly. However, these re-training efforts happened thanks to the private initiative of doctors and hospitals - the state never organized any re-training courses that would have addressed this. In addition, the ensuing panic led to the hoarding of deficit medications, which left many in need of prescription drugs looking for them through personal connections. All that the medical authorities could do, lacking the ability to start an emergency procedure to quickly import deficit drugs, was to urge the public not to overstock and not to self-treat.

All of these issues led to a higher Covid-19 death toll, but also to the overall greater death rate, as overburdened hospitals could not take other emergencies during the worst weeks of the pandemic.

(Almost) no testing

The medical system was not the only one to fall apart due to late reorganization by the authorities. The contact tracing and testing system, managed by the Regional Health Inspectorates, was also overwhelmed in the autumn after not being properly reinforced in the "quiet" summer months. In other countries, the authorities prioritized testing and contact tracing capacity during the spring lockdown and subsequent months. In Bulgaria, this simply did not happen - levels of testing in October-November were actually lower than in the summer.

The biggest inspectorate in the country, the one in the capital, was left with only ten health inspectors to take samples from quarantined people across town. The result was that only about 200 PCR tests and just as many quick tests were performed daily to quarantined and contact persons per day in the month of August in a city of over 1,5 million people. The result of this negligence was that Bulgaria held a steady bottom place in terms of testing not only in the EU, but in Europe as a whole, with neighboring non-EU countries like Serbia (89,000 tests per million) and N. Macedonia (58,000 per million) testing much more than Sofia (46,000 per million).

In practice, this meant that sick people were roaming free and unrestricted, and it was left to the good will of potential carriers of the virus to avoid spreading it.

"The coronavirus map of Europe makes one thing clear: the richer nations of western Europe have suffered more from the virus than countries in the eastern half of the EU, almost without exceptions," The Guardian wrote in early May 2020. For once, Eastern Europe - the prodigal laggard son of the EU, seemed to be faring much better than the rest. Slovakia, the British media wrote, had recorded 20 times fewer deaths and one tenth of the infection rate of its neighbor Austria at the time.

For three full months of the pandemic, Bulgaria had a total of 2,500 detected cases and only 140 recorded deaths.