| Accent |

|---|

| The protest galvanized simmering public discontent with the authorities and their constant mishaps, bringing the real problems of the country - high-level corruption, lack of rule of law and captured media - to the forefront of debates both here and in Europe |

What a political summer in Bulgaria, ladies and gentlemen! Following years of incessant scandals - from humongous data leaks, water crises cutting off supplies for tens of thousands of people, to pictures of the Prime Minister sleeping next to a drawer full of 500-euro notes, gold and a handgun - it almost seemed that Bulgarians had grown attuned to Mr Borissov and GERB's governing style.

It turned out that this was an illusion - they only needed a spark. It came with one simple, but an extremely effective publicity stunt by Hristo Ivanov, an opposition politician, on a beach seized by Mr Borissov's shadowy accomplice, Movement of Rights and Freedoms (MRF) honorary chairman Ahmed Dogan.

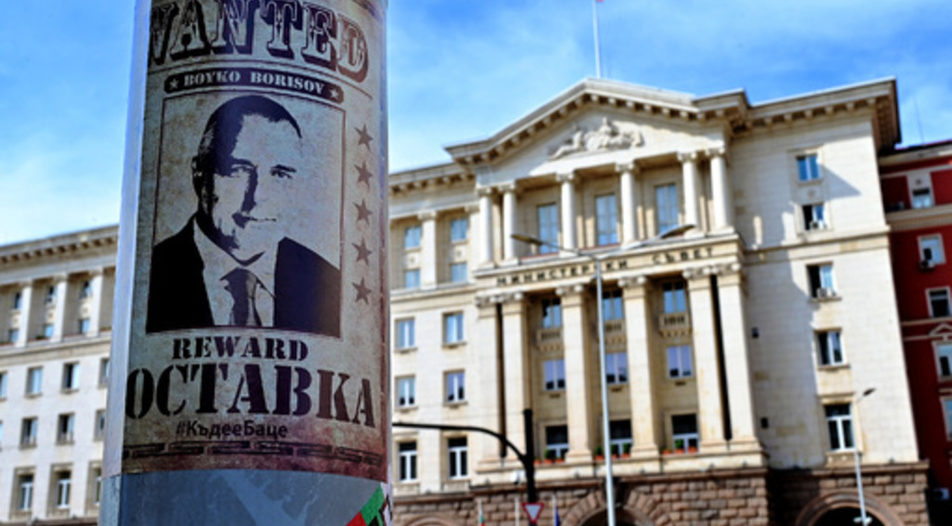

Since then, thousands of Bulgarians have taken to the streets protesting corruption and government excesses for a hundred consecutive days. Their demands were clear: they wanted two resignations - those of Mr Borissov and Prosecutor General Ivan Geshev, who are both seen as pawns of the puppeteers from the MRF, namely Mr Dogan and media mogul Delyan Peevski - as well as early elections.

Three months into the protests and only six months before the regular elections, it seems that the protests have failed in their goals. It is very unlikely that Mr Borissov will give up power in time to organize early elections, especially with the COVID-19 epidemiological situation worsening by the day. Mr Geshev is hardly on his way out, either. So, did the protests fall short, or is there more to them than meets the eye?

A long time ago on a beach far away

On 7 July Democratic Bulgaria co-chair Hristo Ivanov landed on a beach in the Rosenets area near Burgas to demonstratively plant a Bulgarian flag on the public territory which was illegally occupied by Mr Dogan, who built a luxurious mansion there. He was, however, tackled back into the water by National Protection Service (NSO) guards who protect the ex-politician for undisclosed reasons - all while broadcasting live on Facebook (a favourite publicity tool of the prime minister himself).

This triggered a squabble between Mr Borissov and President Rumen Radev, who share responsibility for controlling NSO, over who ordered Mr Dogan's protection. In the end, State Prosecution agents - nominally for a completely different reason, unexpectedly raided Mr Radev's office on the following day. Many citizens perceived it as an attempt by the government-friendly Prosecution to pressure, or even eliminate the President, who has long positioned himself as the strongest - and practically only - an institutional opponent of Mr Borissov.

The result was an outburst of public anger, with thousands of people from various political backgrounds, including Socialists, supporters of the President, liberal youth, political opportunists etc. joining in the protest to oppose the arbitrariness of the Prosecution on the first day. Under the motto of "Save Democracy," the protests continued - usually culminating in peaceful marches that closed down key boulevards in the evenings.

What did the protest achieve?

Although the three main demands of the street have not been met - and were unlikely to have ever done so - dismissing the marches as a failure would be unfair.

First, the protests led to the resignations of a number of key members of Mr Borissov's cabinet due to allegations of closeness to Mr Peevski and the MRF. Mladen Marinov, Minister of the Interior, Vladislav Goranov - of Finance and Emil Karanikolov - of Economy were all forced to leave the office with the purpose of trying to dismiss claims that GERB is dependent on MRF. The action rebounded on Mr Borissov - most-read into the act an acknowledgement that GERB indeed had ties to MRF that it wanted to show it can sever. Two other ministers - Nikolina Angelkova of Tourism and Danail Kirilov of Justice - also left the cabinet after very uninspiring tenures, highlighting the personnel problems of GERB.

The second big gain for the protestors is that they managed to bring to the international stage almost every problem currently dogging Bulgarian politics. This was a two-sided process: unlike in 2013, protesters managed to flag clear-cut demands and translatable messages that alerted foreign observers. Also, six years of GERB rule had provided a series of slippery scandals to use as source material for placards and posters. On the other hand, international media finally started producing more sophisticated and detailed analyses of the situation in the country, covering the protests in a much more nuanced and in-depth manner than in 2013.

Most importantly, observers realized - and translated successfully to the EU - that the corruption and abuse of power in Bulgaria are potentially just as dangerous to the Union as Hungary and Poland's democratic backslide. This resulted in a critical European Commission report and a damning European Parliament memorandum that could not have been blocked even by Mr Borissov's staunch German and European People's Party (EPP) allies.

As for the Prime Minister, rarely has he ever been so sidelined. He hardly, if ever, appears in Sofia. Mostly he surfaces in staged Facebook Live videos in which he is driving ministers in the backseat of his jeep or discussing pension hikes with grateful crowds in villages far away from the capital's roaring central squares. His videos, usually spammed by party well-wishers, started to be lampooned as they veered from the ridiculous to the absurd. The latest example was the mockery Mr Borissov attracted when he sat with his Finance and Regional ministers on a couple of logs next to a wooden cabin somewhere in the forest, announcing that the Moody's rating agency increased Bulgaria's long-term credit score.

What's the situation in the government?

Cases like this one practically showcase the impotency or unwillingness of the Prime Minister to engage in any sort of meaningful debate with protesters, which leads to support for GERB dwindling to the party's core base.

While all polls in the past three months have registered diminishing support for the ruling party and its nationalist acolytes, the latest Market Links survey showed that GERB and their main opponents, the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP), have now reached parity, with about 22,2-3% of declared voters backing each party. This is a baffling result considering that electoral support for the Socialists has also waned.

The reluctance and impotence of the members of government to engage meaningfully with protesters and intellectuals have led to another unexpected win for protesters: the pro-government narrative has been broken. Talking heads and analysts close to the status quo are mocked by the public for their template justifications of government mishaps and attempts to downplay or demonize the protests. Closeted government mouthpieces are ignored or made fun of. Dissenters discussing real problems have unprecedentedly taken the central stage, instead of fake scandals designed to distract the general public.

In essence, the protest galvanized simmering public discontent with the authorities and their constant mishaps, bringing the real problems of the country - high-level corruption, lack of rule of law and captured media - to the forefront of debates both here and in Europe. This is no small gain.

In this situation, the big question is: why does the Prime Minister defy all calls to resign and why does he do so at the cost of his ratings? An August Alfa Research poll showed that support for Mr Borissov is at its lowest point - 23%, whereas his main political opponent Mr Radev is trusted by 43,6% of respondents. The GERB-led government, which has never attracted much sympathy anyway, is only backed by 13,3% of respondents. The party and its leader can hardly recover from this image blow without significant changes. And this is not the only thing they have to fear - there are enemies at their gates, some of whom were past allies (see the box on the fresh contestants for power).

How long will Borissov hold on?

The simple answer is that Mr Borissov does not have much choice. His resignation now would remove him at a crucial moment for EU budget discussions and domestic appointments. The completion of the Turkish Stream project, which in Bulgaria is known as Balkan Stream in an awkward attempt to disguise its Russian genesis, needs to be completed before he departs; commitments have been personally made to Russian President Vladimir Putin.

In order to buy themselves some time, Mr Borissov and his party embarked on evasive manoeuvres and a spending spree on unplanned social expenses. While expected, both moves come with their own political and economic risks, respectively.

Mr Borissov even tried to deflect protesters' demands for his resignation with a call for "a full restart of the system" by introducing a supposedly thorough revision of the Bulgarian Constitution. The idea was that all the systemic demands of the street be addressed in the new document.

While the process is absurd and has been ridiculed by every serious observer and constitutionalists, it seemed to have played its part in the circus of the cabinet. It distracted debates for a few weeks and it made early elections unfeasible - winter and a potential second round of the pandemic are coming, and the elections should take place in March-April next year anyway.

Mr Borissov does not shy away from buying off his time in office - literally. In the past few weeks, the cabinet has gone on a spectacular last-minute spending spree. For every pensioner - 25 euro on top of the pension until spring of 2020 to alleviate the alleged effects of COVID-19, which are actually minimal to pensioners because they never had their businesses shut. Proposals for expanding parental care support to every family and not only to those in need. Increase of administrative expenses for most municipalities. Grants and cheap credits for suffering companies. Money for roads. Proposals to buy a new batch of F-16s to mute potential US discontent with the advancement of Russian energy projects.

It is hard to estimate the pledges the government has made so far, but only for August the Council of Ministers voted 500 million euro in unplanned emergency spending. Bulgaria, which prides itself as a fiscally conservative champion at the EU level, might be overspending because of its Prime Minister's attempt to cling on to power for a few more months. At the same time, international financial bodies estimate that the decline to GDP of the country will be somewhere between -4 and -8,5% of 2020.

Where do we go from here?

The political situation in the country is obviously dire, so here are some options ahead.

One would be for Mr Borissov to finally concede, resign, ask his parliamentary majority to dissolve the current National Assembly and immediately call for early elections in about three months' time. A cabinet appointed by President Rumen Radev would organize these. Of course, this is also the most unlikely scenario, as Mr Borissov has made clear that he fears that this may sway the elections against GERB. Additionally, as the number of COVID-19 cases is on the rise already, it is very unlikely that a January vote would be safe for epidemiological reasons.

The second option - as voiced by the MRF - is that Mr Borissov resigns and dissolves his cabinet, but GERB keeps the mandate, nominates a new Prime Minister and organizes an expert cabinet alongside the BSP. So far Mr Borissov has been dodging this option and it is far from certain that even if he endorses it, he would be backed by the BSP.

The third and most likely scenario is that regular elections occur after a difficult winter in which the Bulgarian healthcare system has been strained by the COVID-19 and the budget - by the government gifts. GERB will be weakened additionally after ten months of upheaval and will try to bring in new faces, and hope that the fragmented opposition continues speaking without a common voice. This might lead to a decline in the number of MPs in the next election for Mr Borissov's party, as well as for a colourful parliament with either a floating majority or a minority government.

In all this, there are three factors that need to be observed - the actions of Prosecutor General Mr Geshev, the level of public support for President Radev and the economy. Mr Geshev has kept a lower profile in recent weeks, in sharp contrast to his loudly announced operations against moguls and Russian spies at the start of his mandate and visits to villages and smaller towns to showcase how the Prosecution fights petty crime. Of course, he could always revert to a more proactive mode if the circumstances allow or demand it.

The same applies to Mr Radev. After a couple of very active weeks at the start of the protests, he has taken a lower profile, limiting himself to demanding the resignations of Mr Geshev and Mr Borissov and only opposing them through institutional means. These include threatening or taking the certain decision to the Constitutional court or back to Parliament, which he used to do anyway even before the protests. The Presidential elections come just a few months after the regular parliamentary elections in November 2021. So the question of whether Mr Radev pursues a second mandate or takes some other political path to oppose GERB - even through the creation of a political force of his own - would soon be relevant.

And the economy is by far the most important issue here: In such a situation even a small crisis can evaporate any remnants of public support for the government and force Mr. Borissov to resign. He knows that full well and is trying to avoid such a scenario. How successfully though, is not something dependent entirely on him.

People and organizations to watch

Hristo Ivanov and the Democratic Bulgaria coalition

After sparking the fuse of anti-government sentiments at the beginning of July, Democratic Bulgaria rose to prominence and its co-chair Mr Ivanov briefly acquired a heroic status for his daring raids near Burgas. The party increased its prospective share of the vote threefold in a matter of weeks but then stagnated at about 9,6% of the vote (in Market Links' latest survey). It is likely that the rule-of-law-focused coalition might have reached the top of its potential, but it also bears the negatives from the protests i.e. the blockades, although it had little connection with them formally. The party, which derives its support from centrist urban liberals, would face a backlash if it enters a coalition with any of the other major actors, even if it is under the banner of establishing a rule of law order.

Slavi Trifonov and the There is such people party

The TV host and now political leader kept a relatively low profile during the summer of protests, speaking up against the government selectively through his show or his Facebook profile, but never appearing in the crowds like most other opposition political leaders. Currently, the party enjoys the serious support of about 11% of voters, despite having almost no public faces beyond Mr Trifonov and the team of his show. According to Toshko Yordanov, one of the scriptwriters from his editorial team, the party will not enter "any coalition that would include the mafia" of parties including GERB, BSP, MRF, Republicans for Bulgaria and the far-right factions. Nothing certain is known yet about the motives or strategies of the party however, neither about its decision-making structure.

Maya Manolova and the Rise up, Bulgaria movement

Ex-Ombudsman and BSP MP Maya Manolova is another active face during the protests, where she appears under the banner of her Rise up Bulgaria movement, surrounded by forgotten faces from across the political spectrum. She maintains that she will not turn to Rise up, Bulgaria into a political party, but would rather make a wide anti-GERB coalition with smaller parties. Sociologists give her about 2,5% of the vote at this time.

Tsvetan Tsvetanov and the Republicans for Bulgaria party

Mr Borissov's ex right hand in GERB Tsvetan Tsvetanov, who was ousted from the party after a real estate purchase scandal last year, launched his party called Republicans for Bulgaria at the end of September. As the name clearly states, it is supposed to be a conservative, pro-US and EU party. Yet Mr Tsvetanov is a doubtful figure and a highly unlikely candidate for a thorough reformer. Drawing members from Bulgarians returning from abroad and conservative intellectuals, the party is also managing to attract members of GERB who had been loyal to Mr Tsvetanov in the past - MPs, mayors and sometimes entire local party structures. It is unclear what the party's main goal is at this moment, but Mr Tsvetanov underlined that there will be no fourth mandate for Mr Borissov. One potential possibility is for his party to try a coalition with GERB, but without the current Prime Minister at the helm. Mr Tsvetanov said that his biggest opponents are BSP and MRF and a potential ally - Democratic Bulgaria. So far the party has not registered on sociological surveys.

The Poisonous Trio

The team of three that organizes the stage, microphone and speakers for the daily protests consists of lawyer Nikolai Hadjigenov, who became а vocal critic of the government, especially over a series of cases of police brutality, sculptor Velislav Minekov; and PR specialist and former radio journalist, Arman Babikyan. While the trio has not yet expressed clear political aspirations beyond the basic protest demands, this might change in the future.

Vassil Bozhkov and the Bulgarian Summer project

In mid-August, mogul Vassil Bozhkov, who is currently self-exiled in Dubai after the government (called a "junta" by him) pursued his gambling business, announced he is "granting" Bulgarians a platform for direct democracy called Bulgarian Summer. The website allows for the registration of volunteers and partners who ought to become the backbone of a future party backed by Mr Bozhkov, but not much else is known about it right now.

- The Nationalists

The three parties that used to be part of the United Patriots coalition, as well as the far-right Volya ("will") of now-convicted businessman Veselin Mareshki, would have a tough time getting back into parliament. Currently, the coalition gathers about 2,2% of the vote and the only viable party from it is VMRO of Defense Minister Krasimir Karakachanov, which desperately tries remaining relevant by stirring anti-Roma, anti-Macedonian and anti-liberal ideas, too little success. Nationalists suffered a lot from Democratic Bulgaria's successful repositioning as an anti-MRF force.

BSP after Ninova's reelection

Last, but not least, comes the Socialist party, which is currently undergoing a process of consolidation after the reelection of its leader, Kornelia Ninova. Now that Ms Ninova has won the popular vote in the party and has a free hand to extinguish the supposed pro-GERB wing within BSP, it is very unlikely that the Socialists might pursue a grand coalition with GERB. Bearing in mind that right now the MRF are a toxic partner for any political force, it is likely that their traditional allies from BSP would be reluctant to give them a hand. It is not unlikely that the socialists might call for a tactical anti-GERB coalition, but this could hardly work out under Ms Ninova's uninspiring leadership.

MRF - the shadowy eminence

The semi-ethnic, semi-oligarchic party is only marginally affected by the bad publicity it has been getting in the last couple of months. It formally gets about 8% of the vote, but it is always hard to measure their real support base, as it is mostly focused in the poorest, most alienated Roma and ethnic Turkish communities. While the MRF leadership is benefitting from the hidden partnership with GERB, the party rank-and-file are getting frustrated after being out of power for the past seven years. While it is unrealistic that any political force would hold hands with a currently very toxic MRF, it is certain that the party would try to forge under-the-radar deals with whoever wins the next elections.

| Accent |

|---|

| The protest galvanized simmering public discontent with the authorities and their constant mishaps, bringing the real problems of the country - high-level corruption, lack of rule of law and captured media - to the forefront of debates both here and in Europe |

What a political summer in Bulgaria, ladies and gentlemen! Following years of incessant scandals - from humongous data leaks, water crises cutting off supplies for tens of thousands of people, to pictures of the Prime Minister sleeping next to a drawer full of 500-euro notes, gold and a handgun - it almost seemed that Bulgarians had grown attuned to Mr Borissov and GERB's governing style.