- Alienation will only increase and with time could lead to disruption on the political scene

- Regardless of whether young people consider themselves left-wing or right-wing, they are all aggrieved about social inequality, corruption and poverty

Call them the Silent Discontent Generation. They are dissatisfied with the status quo - they don't like existing political parties, disagree with the old definitions of "left" and "right" and think that nobody properly represents them. But don't expect them to start a revolution. Meet Bulgaria's under- 30s - young, discontented and potentially dangerous.

Bulgarians under 30 see inequality, corruption and poverty as today's major problems; they define themselves as free, think that profit and democracy are important and most of them (61%) want to stay in Bulgaria. At the moment they're not politically active, but they demand to change even though they're not always certain how to bring it about. At some point, they will have to mobilize and that looks likely to reshape the political scene.

A game for adults only

When politics ceases to matter, this means that people are living well, according to an old political science axiom. While Bulgaria is definitely more affluent, it hardly explains the collapse of interest in politics over the past three years.

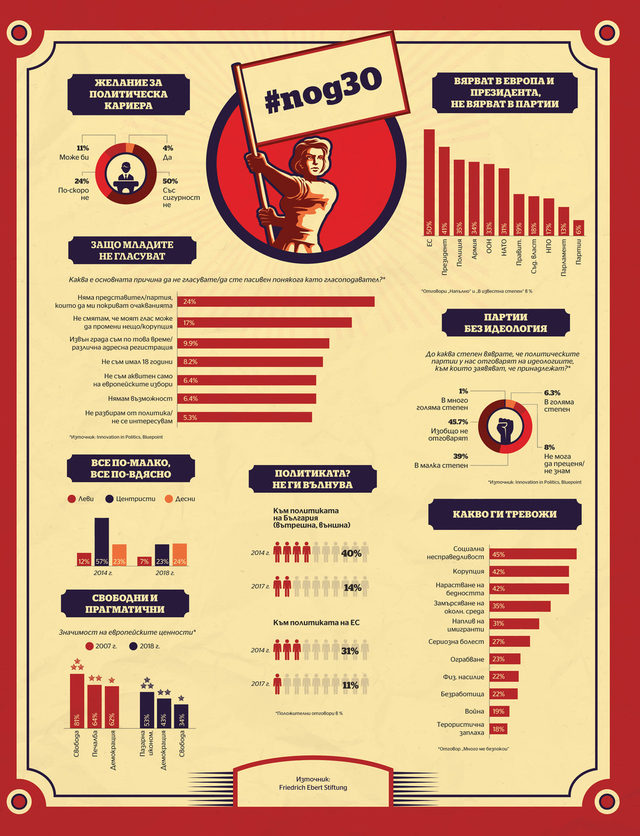

In 2014, 40% of young people said they were interested in politics, while in 2017 the figure was only 14%, according to a survey conducted among people under 30 by Gallup International on behalf of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation. The most likely cause for the downturn seems to be young people's belief that political activism counts for little. Especially since the protest wave in 2013-2014 failed to reap tangible results and Bulgarian politics simply didn't bow to popular protests.

"Young people in Bulgaria are strangers to the political process. They consider it to be a game for adults only and don't feel as though they are represented in it," says Boris Popivanov, associate professor of sociology and co-author of the survey. He believes this feeling of underrepresentation places Bulgaria's young people in the same category as other minorities and the disabled.

Mihail Stefanov, the creator of Bridge Fest Vidin, a youth art festival, explains that in recent years more young people are volunteering and taking part in various initiatives, but these simply don't cross over into the political sphere. What is missing is trust in the political system. "It could be built slowly when words and deeds are not in conflict," says Stefanov.

Perhaps influenced by the pessimism of their parents, many young people not only see no reasons to vote but wouldn't even consider joining any traditional political formation. Those who do so, however, are viewed with suspicion. The young feel politically alienated from the youth structures of the existing parties, hence their reluctance to join. So they are populated mostly by family relatives and self-servers and the political system seems doomed to just preserve the status quo.

Neither left nor right, all is wrong

The Guardian and The Economist highlight a global tendency called millennial socialism - the emergence of a new kind of a left-wing doctrine. Millennials veer much more towards socialism because of rising inequality and growing frustration with today's politicians' failure to deal with major problems stemming from the structuring of the global economy. Those young people, who attend climate protests today, will be in governing positions tomorrow. The popularity of politicians like Bernie Sanders and Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez in the U.S., and Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, proves socialism is back in fashion.

In theory, the same should apply to a great extent to Bulgaria which tops Eurostat's rankings as the country with the biggest income inequality between the upper 20% and the lower 20%. Yet a 2014 survey of 10 Southeast European countries showed that Bulgaria and North Macedonia are the only countries where more young people identify as right-leaning than left-leaning. In 2018, the attraction of the left has fallen even further in Bulgaria - 24% consider themselves as right-leaning and just 7% as left. "So socialism does not appear to be looming," says Boris Popivanov. Which is not to say that there isn't a generation on the horizon with a new view of the world.

Youngsters in Bulgaria also consider the current economic situation and rising inequality as unfair and definitely dislike today's political parties. But the label "left" is still tainted by the stigma of the communist past. In addition, the survey shows that children tend to adopt the political attitudes of their parents, who in the 1990s protested against communism and demanded a change of political regime.

No ideology, please, we are pragmatic

Just don't rely too much on these labels. Up to 45% of young people in Bulgaria already feel they have no place on the political spectrum. A massive 34% who four years ago defined themselves as "centre", have simply disappeared. The political chaos of recent years could probably be blamed for the destruction of old labels.

But the main reason perhaps is that what excites young Bulgarians goes beyond the ideological divide, as they consider social injustice and corruption to be the main problems in their country. As many as 44% of those who define themselves as right-leaning, answer "Yes" when asked if state ownership in business and industry should increase. Solidarity and equality are valued higher than the market economy.

At the same time, democracy has receded from its second position in the ranking of basic values. That should be great news for the Bulgarian Socialist Party (BSP) which has been trying to strike the chords of dissatisfaction. Yet, young people put freedom at the top of their list of values, while making a profit - surprisingly or not - comes second.

"This is a very pragmatic generation," concludes Parvan Simeonov, a co-author of the survey. He points out that young people don't feel attracted to political parties based on whether they are left-wing or right-wing but on whether they are new and offer solutions to problems. Two-thirds of young people in Bulgaria say a "strong party representing the common people" is needed.

But if you expect those new generations to contribute to creating such a party, think again. First, because they simply don't want to. Even in 2013, the year of the most significant civic activity of this decade, the protest movement didn't give birth to a political formation that could compete with the established parties.

A fundamental reason, not only in Bulgaria but worldwide, is waning inter-personal skills. Most young political activists favour participation in new online platforms that are highly polarized, strongly ideological and focused on achieving the viral effect, not inclusivity. Those echo chambers do not help to forge the art of compromise with those of slightly different views.

According to a BluePoint survey conducted on behalf of the EU-wide consultancy Innovation in Politics Institute, almost half (47%) of people under 30 think the main parties do not represent the ideologies they claim to espouse - or at least any tentative movements in this direction are viewed sceptically, For example, BSP tried to flirt with abolishing the flat tax rate (which the socialists themselves introduced when they were in government in 2006) and have put forward ideas similar to the British Labour Party's proposal to give workers a 10% share in large companies. These attempts don't seem to have broadened their young electorate. On the contrary, left-leaning youngsters are shifting their activism online platforms. And they do it much faster than their right-leaning peers because of the stifling domination of BSP over the left political spectrum.

The silent discontent generation

All that means that young people in Bulgaria don't trust old parties. They are unhappy with the status quo but prefer not to set up new political organizations. The survey shows a critically low level of trust in institutions such as government, parliament and the judiciary.

This is a potentially dangerous situation, not only because it leaves room for the sudden emergence of new massive populist movements (look at the far-left 2017 presidential candidate Jean-Luc Mélenchon in France or the country's Gilets Jaunes, known as the Yellow Vests' Movement). The lack of representation multiplies every disgruntlement.

On the other hand, such simmering discontent is an opportunity for change. Young people today are much more interested and informed about European politics, follow events in countries other than their own and could be inspired by some good examples like the political upturns in Slovakia or even the active anti-corruption movement in Romania. Surveys show that those who participate in protests when young, are more inclined to do so later in life and the number of protests has grown in recent years.

Of course, there is no guarantee that they would not follow more populist paths, like the one in Ukraine where a politically inexperienced TV-star became president: Volodymyr Zelensky already has copycats in Bulgaria.

In fact, the tendency to shun politics is not unique to Bulgaria; it is also visible in other countries in the region, the surveys of the Friedrich Ebert Foundation show. Is that so bad?

"Yes, because politics influence the economy, not just the other way round," says Boris Popivanov. There is no magic wand or social media activism that can solve the current issues of inequality, corruption or weak institutions. Sometimes, you need to get your hands dirty with politics.

- Alienation will only increase and with time could lead to disruption on the political scene

- Regardless of whether young people consider themselves left-wing or right-wing, they are all aggrieved about social inequality, corruption and poverty

Call them the Silent Discontent Generation. They are dissatisfied with the status quo - they don't like existing political parties, disagree with the old definitions of "left" and "right" and think that nobody properly represents them. But don't expect them to start a revolution. Meet Bulgaria's under- 30s - young, discontented and potentially dangerous.