Bulgarian politicians are often derided at home for their supposedly blind acquiescence to every whim of EU bureaucrats. In sharp contrast to this perception, over the past two years, the Bulgarian government and members of the European Parliament worked hard to prevent amendments to the so-called Mobility Package 1, a set of EU rules regulating lorry drivers' working times and remuneration. The changes increase social benefits for employees and decrease the periods during which road transport companies registered in an EU member state can operate in the internal markets of other member states. For those companies registered in Bulgaria and the other Eastern European countries, which have burst into the more lucrative markets of France or Germany, the high-minded new EU legislation sounds like a death knell. "They want to destroy our business model," says Angel Trakov, chairman of Bulgaria's Union of International Haulers. Under pressure from the road transport sector the defeat of the Macron Package, as the new legislation is colloquially known in Bulgaria, has become a matter of national pride in Sofia. Ever since the European Commission officially unveiled the Mobility Package 1 in May 2017, Bulgaria's government has attempted to fend off any measure that could hinder the operations of Bulgarian hauliers in the markets of other EU member states. Yet, Bulgaria's determined "No" to the new legislation had limited success. The opponents of Mobility Package 1 secured some concessions but nevertheless, the new road haulage rules will be significantly amended to the detriment of Eastern European companies once the new European Parliament convenes after the May elections. The question is why Bulgaria, despite all efforts and mobilization, has been unable to play its trump cards in negotiations over the package. Bulgaria's stake The new transport legislation, when adopted probably later this year, will hit Bulgaria hard. The road haulage sector employs, directly and indirectly, around 6% of the labour force in Bulgaria, or 120,000 people, according to rough estimates (Bulgaria's National Statistical Institute doesn't have precise numbers).

Bulgarian hauliers have complained of an unequal treatment since 2014 when Germany and later France launched legislative curbs on the access of foreign transport companies to their markets. The so-called Macron Law, which introduced those restrictions in France, was the most significant achievement of French president Emmanuel Macron in his previous capacity as minister of the economy back in 2015.

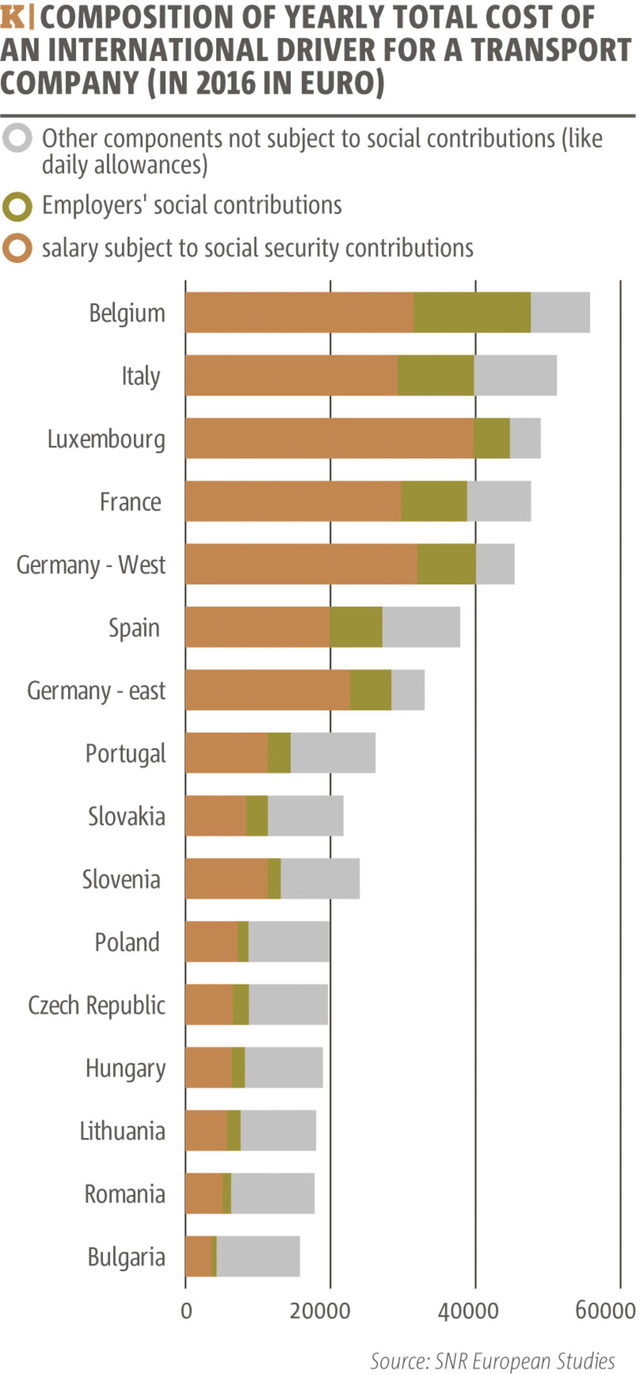

In a nutshell, the new legislation limits Eastern European companies' access to well-paying Western European markets. Hauliers from the East will need to make sure that their drivers return home and get rest at least once every four weeks. The European Parliament supported an amendment that would require lorries to return to their home bases as well, which means that companies from countries at the EU's periphery, like Bulgaria or Latvia, can operate non-stop for no more than two weeks in the lucrative French or Dutch markets. In addition, drivers need to be paid the local minimum wage (if it is higher than that of their native countries) as soon as they cross the border, depriving Eastern European haulers and drivers of their cost advantage.

This advantage, of course, comes with an unpleasant twist - lorry drivers rarely spend the night in a hotel, sleeping in their truck cabins instead, and often go back home only once in three months when they must take their required mandatory leave under current legislation. But many employees take these jobs because they pay well - at least by the standards of their home countries. The question is: should anyone stop workers from willingly Western European governments, trade unions and companies say "Yes". According to them, drivers are exploited by their employers who refuse to abide by higher social standards in the West.

Eastern European governments and transport companies say "No", maintaining that the free market allows everybody to pursue their best interests, giving Eastern European drivers the chance to earn wages on a par with their Western European counterparts.

For the "Road Alliance" (Austria, Belgium, Denmark, France, Germany, Italy, Luxembourg, Sweden and Norway), Mobility Package 1 will prevent unfair competition caused by "social dumping", i.e. by companies based in countries with lower salaries and social standards. In his recent letter to European citizens, Emmanuel Macron painted a picture of a stronger, re-energized European Union but played down the importance of the bloc's single market. "A market is quite useful, but it must not make us forget the need for protective boundaries and unifying values," wrote the French president.

The alliance of "like-minded countries" (a fluid coalition of member states led by Poland, Bulgaria, Latvia, Lithuania, Estonia, Hungary and Romania) takes the opposite view. In their opinion, the new legislation is another example of protectionist policies disguised as social rights concerns that aim to prevent Eastern European companies from competing on equal terms with their Western European counterparts.

"I have the feeling that if companies from big countries do business in Eastern Europe, it is called a free market. If Eastern European companies do business in the West, it is unfair competition and social dumping," said Bulgarian Socialist MEP Peter Kouroumbashev, voicing sentiments shared by many East Europeans.

On the one hand, the restrictions could reduce the revenue of Bulgarian transport companies, driving many of them out of business and giving a boost to yet another wave of skilled worker migration. On the other hand, the regulations for lorry drivers could open the floodgates to even more legislative ideas to fight "social dumping" from the East. Under the pretence of improving the livelihood of the East Europeans, they aim to prevent them from seeking better employment opportunities in the West without permanently relocating there.

The Bulgarian impasse

Sofia did have a rare opportunity to effectively influence the EU's legislative process. Bulgaria held the rotating presidency of the Council of the EU in the first half of 2018, precisely when EU member states and the European Parliament had to agree their negotiating positions on Mobility Package 1.

In order for a piece of EU legislation to pass, the Council comprising the member states' ministers, and the European Parliament, both need to agree. The country holding the rotating presidency could steer the Council agenda for six months and then negotiate with the parliament. Even though the role requires impartiality, member states rarely shy away from pushing their own agenda.

Although Sofia had this trump card, it was unable to change the outcome of the negotiations. The "Road Alliance" countries firmly rebuffed all attempts by the Bulgarian presidency to push for a common position among member states in the Council of the EU. They claimed that Bulgaria's proposed amendments served only its own and its allies' interests.

The legislative process in the European Parliament followed a similar path, although a group of Eastern European MEPs, mainly from Poland, Bulgaria, Lithuania and Romania, mounted a catenaccio-style defence against the amendments.

Bulgaria was unsuccessful in its attempts to thwart the Mobility Package 1 largely because the coalition of countries opposing the legislation was weak. For example, Central European countries like the Czech Republic and Hungary, which are close to Germany's market, had no serious objections to the requirement for drivers to return home more frequently - a proposal that hurts more seriously peripheral countries like Bulgaria or Lithuania.

Once small concessions were made to Prague and Budapest in the course of the negotiations, the Czech Republic and Hungary left the coalition of the "like-minded countries". While in December 2017 15 Member States opposed Mobility Package 1, by June 2018 their number had fallen to eight countries. As usual, the determination of a few countries - namely France and Germany, beat numbers.

Bulgaria, however, had some problems of its own making.

In order to get what they want, EU Member States have to play a long-term strategy of giving and take - frequently one piece of legislation could be traded for support for another one. Bulgaria's government seems not very adept at playing such a complex game.

Sofia had a unique chance to use such leverage, arbitrating between different legislative files, while it was at the helm of the Council of the EU. In the first half of 2018, the member states had to reach common positions not only on the road transport legislation but also the amendments to the posting of workers directive. Both legislative acts are connected and both have been pushed forward vehemently by Emmanuel Macron as a part of his "social dumping" agenda. As early as August 2017 Macron came to Bulgaria offering support for the country's Schengen and eurozone membership in exchange for a favourable position on his ideas for fairer competition in Europe. It seems Sofia fell for it hook, line, and sinker.

Instead of dragging its feet on the posting of workers directive until it had secured a better deal on Mobility Package 1, Sofia hastily concluded the negotiations. The Bulgarian presidency of the Council of EU, for example, was not in a hurry to proceed with the Gas Directive amendments which introduced more regulations over gas pipelines and were regarded as contrary to the interest of new infrastructure projects in Bulgaria. This made many in the European Commission nervous.

Sofia's negotiating efforts were also hampered by the lack of flexibility. Bulgarian transport companies pressed MEPs and diplomats not to make any concessions. "How do we negotiate? You negotiate something that both sides benefit from," Mr. Trakov said, explaining the position of road haulage companies.

As a result, Bulgaria's inflexible stance was rebuffed out of hand. "When you are one to two, you can't achieve every goal you have set, you can probably achieve one-third of what you want," says Petar Kouroumbashev. "If you want to play for everything, the majority will naturally impose its will," he adds. During negotiations in the European parliament, Bulgarian MEPs were not only unable to get their ideas passed, but their opponents actually toughened the regulation proposed by the European Commission.

Domestic pressure to achieve the maximum hampered Bulgaria's efforts to reach a compromise during its presidency of the Council of the EU when it could have negotiated somewhat better conditions for the Eastern European road carriers. Apparently, transport minister Ivaylo Moskovski was afraid that crossing the red lines he had laid down would be treated as betrayal and hence he handed over the issue to the next Austrian presidency of the EU. Austria, however, is part of the "Road Alliance" and naturally the negotiations were taking place in a less favourable environment for Bulgaria. In the end, Sofia said it was not satisfied with any of Vienna's proposals but it was already part of the minority.

As early as 2015 it was already pretty clear that the EU would impose some sorts of regulation on the road haulage market but Sofia was absent from the debate. The Bulgarian authorities now claim that they were unable to intervene in the internal debates of other member states. Thus, when the legislation came out in 2017, it shocked the transport sector, which reacted with disbelief and anger. Later, encouraged by the initial opposition of many countries, the government did not attempt to build a workable coalition at home by stating publicly from the outset what the odds would be on Bulgaria really influencing the outcome of negotiations in Brussels.

Given that Bulgarian business is rather unfamiliar with the way Brussels works (the transport sector has no representative in the EU's capital and it was nowhere to be seen during the debates in the European Parliament), road hauliers took a very firm position, believing that Bulgaria could block Mobility Package 1. As a result, the legislation became an issue of national pride and pride usually beats reason.

West vs East

The Mobility Package 1 and all other measures intended to fight "social dumping" have not been well received in Eastern Europe. Currently, the more or less liberal rules of the EU's single market have allowed Romania's GDP per capita to rise by more than 60 per cent since 2006, while the Czech Republic is already richer than Portugal. Any measure that prevents this process of catching up is regarded as an affront by most Eastern European governments. While policies like Mobile Package 1 may help soothe tempers in the West, they increasingly give rise to anti-EU sentiment in the East.

Over the last decade, there has been increasing talk coming from the more affluent countries about lower taxes and salaries in the new member states, which are blamed for a form of "social dumping". Governments in new member states fear that a new string of legislative proposals on issues such as tax harmonization and the minimum wage, which might seem fine in theory, will follow in the footsteps of Mobility Package 1, stifling their growth potential and producing yet another wave of emigration by skilled workers.

Bulgarian politicians are often derided at home for their supposedly blind acquiescence to every whim of EU bureaucrats. In sharp contrast to this perception, over the past two years, the Bulgarian government and members of the European Parliament worked hard to prevent amendments to the so-called Mobility Package 1, a set of EU rules regulating lorry drivers' working times and remuneration. The changes increase social benefits for employees and decrease the periods during which road transport companies registered in an EU member state can operate in the internal markets of other member states. For those companies registered in Bulgaria and the other Eastern European countries, which have burst into the more lucrative markets of France or Germany, the high-minded new EU legislation sounds like a death knell. "They want to destroy our business model," says Angel Trakov, chairman of Bulgaria's Union of International Haulers. Under pressure from the road transport sector the defeat of the Macron Package, as the new legislation is colloquially known in Bulgaria, has become a matter of national pride in Sofia. Ever since the European Commission officially unveiled the Mobility Package 1 in May 2017, Bulgaria's government has attempted to fend off any measure that could hinder the operations of Bulgarian hauliers in the markets of other EU member states. Yet, Bulgaria's determined "No" to the new legislation had limited success. The opponents of Mobility Package 1 secured some concessions but nevertheless, the new road haulage rules will be significantly amended to the detriment of Eastern European companies once the new European Parliament convenes after the May elections. The question is why Bulgaria, despite all efforts and mobilization, has been unable to play its trump cards in negotiations over the package. Bulgaria's stake The new transport legislation, when adopted probably later this year, will hit Bulgaria hard. The road haulage sector employs, directly and indirectly, around 6% of the labour force in Bulgaria, or 120,000 people, according to rough estimates (Bulgaria's National Statistical Institute doesn't have precise numbers).