The Balkan mountain range, also known as Stara Planina in Bulgaria, forms a natural geographic divide between the northern and southern part of the country. However, in recent years this divide has been more than symbolic. Today, Stara Planina marks the border between the rapid economic development in the south and the stagnation in most of the northern provinces - the difference in indicators like GDP per capita and FDI can sometimes reach 40%.

The lifeline of the southern part is Trakia highway connecting the capital Sofia to the second biggest city of Plovdiv and the Black Sea port of Burgas. There is no such lifeline in the north.

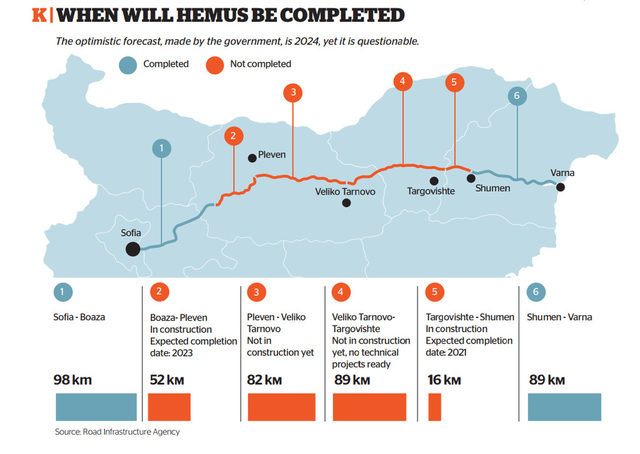

Now the government wants to finally close that gap and complete the construction of the 418-km Hemus motorway that will connect Sofia to the Black Sea port of Varna. The construction began in 1974 - four years before Trakia, and still has about 220 km to go.

No doubt, Hemus highway has been Bulgaria's largest infrastructure project of the past three decades. Funded entirely by the state budget (no EU money was allocated to the project, because the highway route is not part of major transnational corridors), it is promising to expose the worst features of the current model of governance.

Instead of calling tenders, the government has been distributing the money directly to certain companies in advance and with no transparency. This pattern of financing will probably mean taxpayers will pay double the price by the end of construction.

Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves

The Bulgarian Public Procurement Law and European rules dictate that public funds should be distributed transparently and competitively. However, in recent years, the ruling GERB party has found ways to circumvent the rules.

Little by little, authorities created a number of state-run companies and holdings, using the in-house procedure whereby a ministry or a government agency can assign work directly to a connected public company without open bidding. In practice, they swallow billions of taxpayer money and redistribute it directly to private contractors, avoiding public tenders in the process. Such holdings currently exist for energy, water management, petrol.

Road infrastructure also has its representative - "Avtomagistrali". Established in the 1980s, the state-owned construction company (its name means "highways" in English) has become the corruption symbol of Prime Minister Boyko Borissov's third cabinet in both scope and inaccessibility.

Since 2018, the company has been operating as a black box. Billions of levs are going in, new kilometers of roads should be coming out, and nobody knows what goes on in the middle. Within the past two years, close to 4.6 billion levs (2.35 billion euro), or about 4% of Bulgaria's annual GDP, have been poured into the company with no tenders. By the end of 2020, the firm had in its portfolio two government contracts for the construction of the remaining 220 km of Hemus, a contract for stabilizing 74 landslides, and a deal for the construction of a 65 km-long section of the Vidin - Botevgrad road, in northwestern Bulgaria.

Inside the black box

Obviously, Avtomagistrali has no chance of completing all of these tasks on its own in the foreseeable future with its approximately. Yet, it claims it is not using subcontractors (which would make the in-house rule invalid) and doesn't say where the state money goes.

Capital Weekly managed to peek inside the black box and see, at least partially, the mechanism by which Avtomagistrali is operating. Data from sources who requested anonymity shows that 1.2 billion levs in taxpayer money had already been paid out to certain private companies in 2019 and 2020, in an obvious evasion of public procurement rules. Most of the money was disbursed in advance, before any of the actual work has been done.

In an official answer to Capital Weekly, the government's Road Infrastructure Agency states that as of November 2020, it has paid the company a total of 1.13 billion levs under contracts for the construction of Hemus and for stabilizing landslides.

Distributing public resources in this non-transparent way carries the risk of making construction works a lot more expensive. For example, in previous open bids for sections of Hemus, the price ranged between 7 and 9 million levs per kilometer, whereas in one of Avtomagistrali's contracts the price tops 15 million levs. On the Vidin-Botevgrad road, the difference is even higher: - in a previous open tender, the price ranged between 8 and 12 million levs per kilometer, whereas the state-owned firm charges 16 million per kilometer. The contracts even have a clause saying the price may increase - a privilege which companies competing in open bids cannot take advantage of.

Money first, roads after

Despite the huge money distributed, over the past two years not a single site has been cleared for exploitation. Moreover, on large sections of Hemus highway no actual construction activity has even begun. This means that, for the most part, the money transferred from the Road Infrastructure Agency to Avtomagistrali was an advance payment - a scheme that raises several questions.

At best, a lack of competition invariably produces inefficiency. Even if we assume that Avtomagistrali is acting in the most conscientious manner, in the absence of competition we'll never know if another firm can't do the job cheaper and better. If we were to look at it through a different lens, an entire sector of the economy with thousands of employees can be kept on a leash by the government in this manner.

In a normal construction cycle, the risk is taken to a larger extent by the subcontractors who offer guarantees for the quality of their work. In the case of Hemus, Avtomagistrali is the contractor but it is paying other firms for materials, rental of equipment, etc. Private companies' employees are also on site. It's a public secret that Hemus is not being built only by the state company - a fact that even representatives of the private firms involved have confirmed off the record.

That will bring about more troubles in the future. For example, who will be responsible for problems and defects on completed sections? Who will pay for repairs and under what conditions? Who will carry the final responsibility if something goes wrong?

Bulgarian citizens have no information regarding how their tax money is being spent. And the silence of the construction sector on such a topic, where highly profitable options are taken off the table, means that branch of industry is, to a large extent, already complicit and controlled.

The Balkan mountain range, also known as Stara Planina in Bulgaria, forms a natural geographic divide between the northern and southern part of the country. However, in recent years this divide has been more than symbolic. Today, Stara Planina marks the border between the rapid economic development in the south and the stagnation in most of the northern provinces - the difference in indicators like GDP per capita and FDI can sometimes reach 40%.

The lifeline of the southern part is Trakia highway connecting the capital Sofia to the second biggest city of Plovdiv and the Black Sea port of Burgas. There is no such lifeline in the north.