Given its location, Pleven should be the motor of economic development in northern Bulgaria - just like Plovdiv in the south. Instead, the city's most frequent retort is "An economic centre in Pleven - of all places?"

The city has a longstanding industrial tradition, a medical university and a good hospital. In addition, Bulgarian air force pilots study in the adjacent town of Dolna Mitropolia. Yet over the past three decades, it seems to have lost its confidence and willingness to lead.

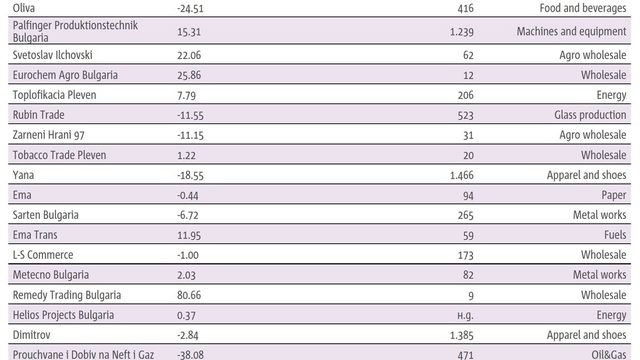

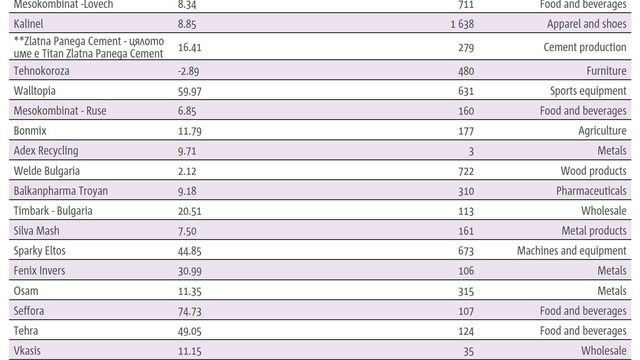

All is not lost, however. You couldn't exactly call it a boom but industry in Pleven, as well as in the neighbouring city of Lovech, is gradually stirring. The arrival of German auto parts manufacturers Leoni and VOSS Automotive in Pleven and Lovech, respectively, as well as the capacity expansion of French malt producer Malteries Soufflet in Pleven, are just some of last year's outstanding examples. Smaller local businesses are also growing and investing in development.

Missing transport infrastructure

Yet the absence of viable transport infrastructure makes Pleven's role as an industrial hub impossible.

"When you don't have a port nearby, or an airport, or a highway, you tell me how any business will prefer Pleven to Plovdiv - with its highways, airport, its accessibility and connectedness? Hence 75% of Bulgaria's GDP is currently generated in southern Bulgaria," says Pleven mayor Georg Spartanski. The long-awaited completion of the Hemus highway, which would connect Pleven to Sofia and the Black Sea, and the planned road tunnel underneath the Shipka peak in the Stara Planina mountain range, are still pipedreams. In short - Pleven just isn't easily accessible.

"Road connectivity and infrastructure determine whether we can make our industrial zones attractive to investors. It is really vital and I'm convinced that if the highway is built, there will be interest in our available facilities," says Miroslav Petrov, governor of the Pleven region, adding that improved transport infrastructure would attract local, as well foreign, investors.

While all this is true, Pleven has untapped opportunities. Coordinated action between the two regional capitals - Pleven and Lovech, just 37 km apart, is still awaited. The regional centres of Sliven and Yambol, in southeastern Bulgaria, by contrast, have been trying to compensate for each other's deficiencies and maximize their positives.

"To date, we haven't held any conversations with Lovech on a joint economic policy," admits Mr Spartanski. His counterpart from Lovech, Kornelia Marinova, explains: "At this stage we don't have any joint projects with neighboring municipalities and regions because our efforts are mostly directed at meeting the requirements for funding under the Human Resources Development and Growing Regions operational programs of the EU." Clearly, the obsession with soaking up available funds still overrides long-term strategic planning by far.

The fountain of hope

The main problem facing Pleven and Lovech isn't infrastructural or political. Sooner or later, the highway will materialize, and so will policies connecting the two cities.

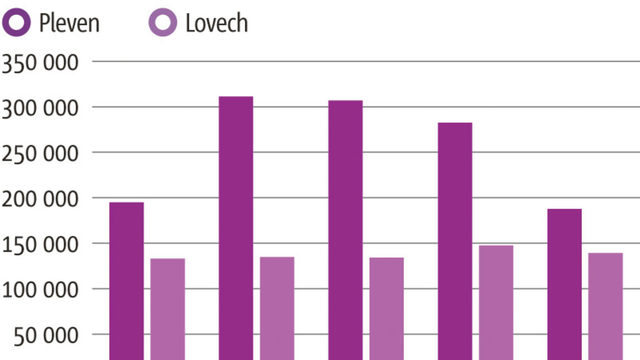

People - that precious and ever-rarer resource - are a serious concern. Both cities have experienced a conspicuous depopulation. "Look at how many windows are lit up at night. In fact, most of them aren't; people have gone," points out Ariana Trifonova from the Pleven Collective volunteer group. A recent warm October early evening highlighted a salient truth - the city centre around the renovated fountain was all but deserted.

However, there are bright spots. The urban environment has won considerable funding in recent years. The development of a modern, integrated public transit system will see a total investment of 57 million levs.

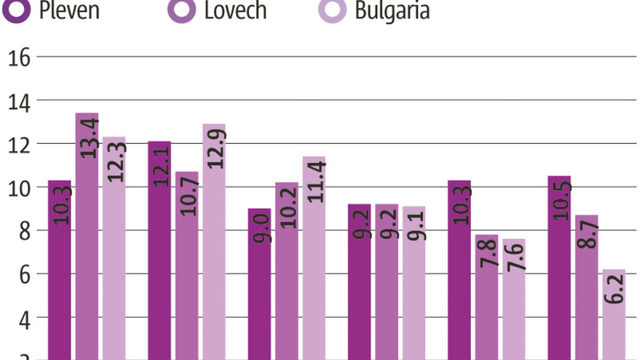

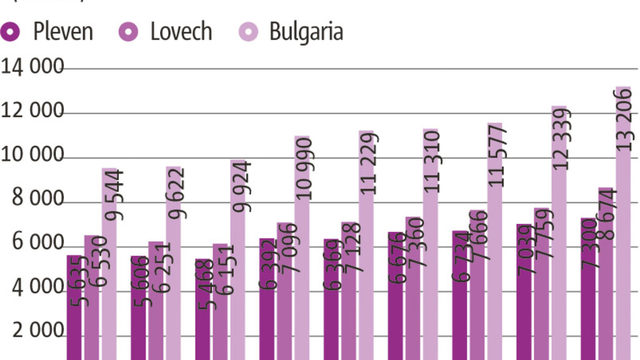

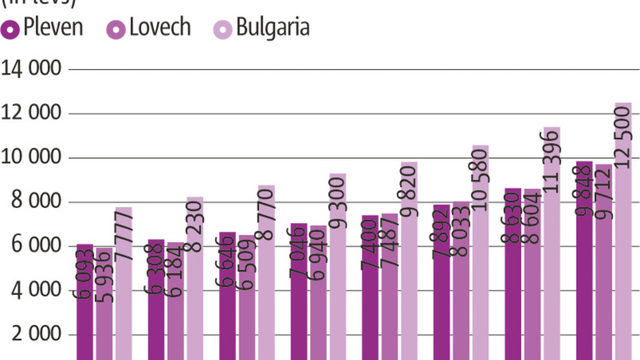

Hopefully, new investors will also help to attract and retain the workforce. For instance, Leoni will employ several thousand people, greatly benefiting the local labour market. This may provide a short-term solution since unemployment in Pleven is gradually decreasing, even though it remains one of the country's highest. According to the latest data by the National Statistical Institute from June 2018, the average monthly net salary was 856 levs in Pleven, and 890 levs in Lovech. This is half of Sofia's median of 1509 levs.

Missed opportunities

As it casts an envious eye to rivals like Plovdiv and harks back to its faded Socialist-era industrial glory, Pleven may not notice that it has overlooked some great opportunities.

For example, the city's medical university (the only one in northwestern Bulgaria) has been increasingly popular in recent years, drawing a large intake of international students. The school's development could uplift the entire local economy, creating opportunities for so-called medical and educational tourism. However, this remains untapped; - there is no marketing of the destination and few innovative businesses around it. A university's biggest advantage is that it attracts talent and hopefully retains a small portion of it in the area.

But, instead of trying to expand and reap its many benefits, local administration and business do little. Sadly, additional obstacles also play their part: "Racism, which most students face daily, is a big problem and makes our lives here harder," says Nezam Anhay, a student from Germany.

Pleven's other missed opportunity is the Aviation Faculty in Dolna Mitropolia. It is part of the National Military University in Veliko Tarnovo. Yet it only enrols a minimal number of students each year due to obsolete and unnecessary admission requirements. And all this on a continent where the aeronautic industry is perpetually growing, where there's a near-limitless demand for pilots and engineers, and where corresponding education costs elsewhere are much steeper.

Few cities, even outside Bulgaria, have such potential at hand.

and future opportunities

Pleven also has more money allocated to culture than many other cities. Nearly 2% of its yearly budget goes toward maintaining an impressive festival season and a philharmonic orchestra, etc. Its expanding and diversifying cultural bill can only help the city prosper and gain popularity. And this is by no means an unattainable goal. People choose to live where they have a sense of belonging, and this means a lot more than just having a job. By this yardstick, Pleven should become a catch.

"We've noticed a tendency lately among those moving to Pleven," says Ariana Trifonova. "They are young families without ties to the city. They do research online and choose it because it's small and good for raising kids since everything is nearby. There are jobs, and if you're qualified there's good pay, while properties are inexpensive. And many young families choose Pleven."

To make the city even more pleasant, its administration should support and reinforce burgeoning grassroots volunteer initiatives, like the one for cleaning the local park Kaylaka, and another that offers cultural tours. After all, it's people and not EU funds that breathe life into a place. And it may turn out that this is the most valuable investment Pleven can make for its future.

| Alucom - mechanical parts for the metro systems in Milan and Dubai The key industries supplied by the Pleven-based company are energy and engineering, and its main clients include ABB, Siemens, and Hyundai |

Alucom, part of Sofia-based Metal Technology Group, has assembled a diverse group of global clients. For example, the main parts for the braking mechanisms of the Milan and Dubai metro trains come from here.

Aside from its other activities, Alucom has established itself in the manufacture of hydro transmissions for off-highway machines (bulldozers, tractors, combine harvesters and steamrollers, etc.). These components can be different kinds of turbine wheels, pistons, guiding mechanisms and covers. One of the main purchasers of these products is U.S.-based Dana Incorporated. Alucom supplies Dana's manufacturing plant in Bruges, Belgium.

Alucom exports 83% to 95% of its annual output, mostly to Europe. The managing director of the company Iskren Nikolov told Capital that lately there's been a marked return of buyers from Chinese to European manufacturers. He cited as reasons the aftermarket and the bigger difficulties in managing deals. According to his observations, the process has developed in the last 12-15 months.

The factory became known in the 1980s for producing road wheels for the Soviet-made T-72 main battle tank. Alucom was privatized in 1997 and became part of MTG Balevski Group owned by Krasimir Bachev, which also includes several foundries.

| On robots, windows, and people Ilina invests in development and robotization, and its exports are growing |

"In 2018, the company invested 150,000 levs of its own funds to purchase a robot for the assembly of heavy insulated glass units," revealed company owner, Boyko Rachev. Until then the operation was done manually. The type of high-end window fixtures on which Ilina has focused its production capabilities requires triple glass insulation and is very heavy and bulky.

The robot is the second of the company's large investments following the 2017 purchase of its 1.5 million levs new plant in the industrial zone of Pleven. The factory employs 50 people and the owner expects production will grow by at least 50% after the improvements. The company's biggest success last year was the start of a partnership with a large construction company from Belgium, which specializes in residential buildings. It completes about 600 apartments a year and it will supply all its windows from the Pleven plant. Until its deal with the Belgian company, Ilina had been working with partners from Belgium, Germany and France. But they are smaller companies ordering a greater variety of products in lower volumes. Since starting work with its new partner, Ilina's exports have stabilized at around 30% of output.

| To fertilize your own growth One of the most dynamic companies in the Pleven region - Lebosol Bulgaria, works with liquid fertilizers |

If there's anything that can fuel northern Bulgaria's faster development, it's dynamic, aggressive, and intelligent companies with global ambitions extending beyond the internal market. Lebosol Bulgaria is a great example. The company is a subsidiary of Germany's Lebosol Dunger, which specializes in the production of liquid foliar fertilizers. Lebosol Bulgaria was established in 2011 and has been growing ever since. For four consecutive years, it has featured on Capital's yearly Gepard ranking of small and midsized businesses.

Presently, the company is investing 1.5 million euro in its own organic and inorganic fertilizer storage facilities in the western industrial zone of Pleven.

The company had a revenue of 6.77 million levs in 2017, clearing a 986,000 levs net profit. The plans for this year are to maintain the 27% growth rate recorded in 2018. The company employs 12 agronomists, who are available to farmers all over the country.

Lebosol Dunger produces a wide range of about 70 products, including compounds for organic farming that sell everywhere in the EU. About 40-50 of them feature on the Bulgarian market, and 15 of those lead Lebosol Bulgaria's sales.

| A slow business The largest snail farm in Bulgaria exports 90% of its production |

Escargots de Bourgogne is one of France's culinary symbols. That's why it's no wonder that the country is the biggest buyer of snails in the world. According to UN data, France's snail imports totaled $48 million in 2017 versus exports of $26 million, on a global market of about $154 million.

But France isn't the only country where snails are a delicacy - Italy, Spain, Portugal and Belgium are also among the largest consumers. With Western Europe enjoying the product, Eastern Europe has become even busier producing it. One of the places where this happens is the village of Krushovitsa near Pleven.

Bulgaria hit the snail market running around the time of 2009 crisis, when a number of small entrepreneurs, attracted by the low initial investments and the promises of a guaranteed market, decided to set up their own farms. Unfortunately, many of them didn't make it because they could not sell their products. Snail farming in Bulgaria is still mostly considered an exotic occupation with between 30 and 50 farms in the country.

The largest of them - in Krushovitsa, is owned by three partners - Petya Kirovska, Ognyan Kirovski, and Stancho Totov.

The snails can be sold in several different forms. One is to sell small live snails for about 5 levs (2.5 euro) per kilo. If the snails are fully grown, the price reaches about 3.5 euro per kg, because of the longer time and higher expenses associated. The third option is to sell processed snail meat for a price that ranges between 10 and 15 euro.

The farm sold about 10 million small snails last year, which is a fifth of its production capacity, says Petya Kirovska, adding that 90% of the output is being exported to Portugal, France, and Greece. "We only sell very small quantities in Bulgaria, mostly to clients placing special orders."

Given its location, Pleven should be the motor of economic development in northern Bulgaria - just like Plovdiv in the south. Instead, the city's most frequent retort is "An economic centre in Pleven - of all places?"

The city has a longstanding industrial tradition, a medical university and a good hospital. In addition, Bulgarian air force pilots study in the adjacent town of Dolna Mitropolia. Yet over the past three decades, it seems to have lost its confidence and willingness to lead.