"You have always been decisive and brave. With a Prime Minister who can intimidate any Thracian warrior, you will make it," said the President of the European Council Donald Tusk in plain Bulgarian during his speech for the opening of Bulgaria's turn as rotational president of the Council of the EU. Tusk is not the first politician who praises Boyko Borissov for his dominating physical presence - former UK Prime Minister David Cameron laughingly mentioned once that he needs to recover after a "Boyko hug".

Yet, even a strong man like Borissov, who had managed to lead his GERB party to election victory three times in eight years, has a few soft spots.

One of them is public protests, particularly if they are targeted at him personally or touch on sensitive issues that spark off a huge media outcry, threatening his popularity. It is easy to understand why Mr Borissov feels so strongly about it: in the winter of 2012-2013, the street protests against his first government became widespread and turned violent, and were followed by disturbing and bloody scenes of a few self-immolations spread over the news. He then chose to resign, saying he "didn't asphalt the roads to see blood spilling on them". The remark, alluding to his favorite topic of public infrastructure improving under his government, helped check the rise in public tensions and prevent linking his name to the ensuing street violence.

Three shades of appeasement

Since then, Mr Borissov has mostly managed to dodge huge public anger by making payouts, postponing decisions or delegating responsibility for unpopular decisions to someone else. All three methods were demonstrated in the months preceding the start of the presidency in January 2018.

First of all, bribe whoever plans to protest or starts protesting. In the months before the start of 2018 there were several calls for protests from different branches of the public service. All of them were curtailed by quick decisions to disburse money. After the Bulgarian Academy of Science unfurled black flags from its building next to Parliament over being underfunded in the 2018 Budget and called for protest of scientists during the Presidency, Mr Borissov found time to meet the governing body of the institution and their subsidy was increased by 15 million levs. A couple of days later, Sofia University Academic Council warned that it will take to the streets and just a couple of days later it received 10 million levs and a new building.

But the educational and science bodies did not punch above their weight, like the servicemen at the Ministry of the Interior did. The single most expensive ministry in Bulgaria, which also costs Bulgarian taxpayers the most per capita (close to 1.5% of GDP, compared to 1% on average for the EU), got 100 million levs for salary increases. This happened after the largest police union played "va banque" in the first days of January, putting up protest posters in broken English alongside one of Sofia's main boulevards where the EU officials' motorcades were to pass and warning of a mass rally upon their arrival.

However, bribery mostly works when demands come from public bodies. In other cases, like the environentalists-led protests against the planned expansion of Bansko ski resort which threatens the UNESCO-designated Pirin National Park, Borissov uses the other two methods - delegating responsibility to someone expendable (possibly not from GERB) and postpone a decision until the tides turn or rallies lose momentum.

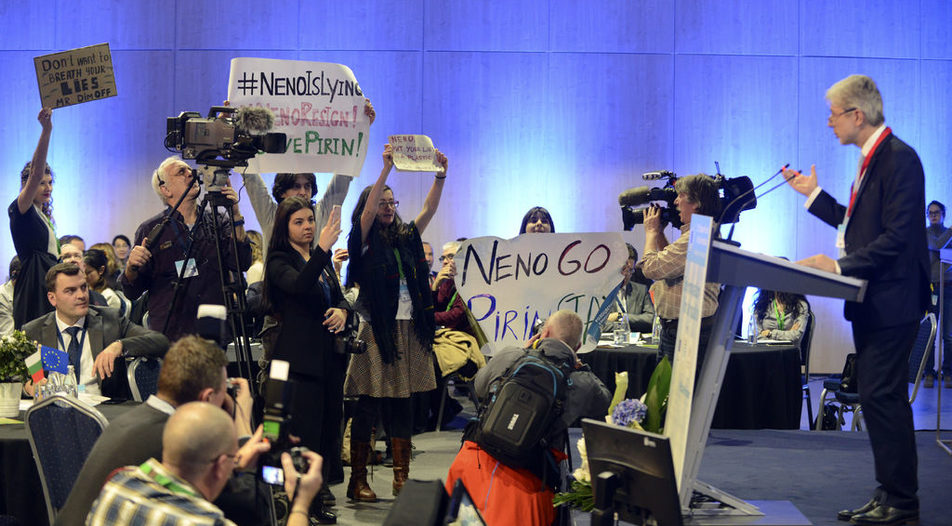

The response to the protest marches against the planned controversial expansion of the skiing zone in Bansko was delegated to a cabinet minister who is not directly linked to GERB - in this case, the self-described "independent expert" and climate change denier Neno Dimov. Although the entire Council of Ministers voted in favor of changes to the management plan of Pirin National Park that open the way for new construction works on its territory, Mr Dimov was the one who took most of the blame.

Postpone until protests die out

When a certain decision leads to public protests, putting it into action can be postponed until the protests run out of steam. This is what the government is currently waiting for in the case of the Pirin protests. Finally, if this maneuver does not produce the desired results, Mr Borissov shows up and reverses the unpopular decision unilaterally - either through his (almost) undisputed control of the GERB parliamentary group, or through the responsible cabinet member. This gives Borissov an additional bonus - the clout of a hero. An example of this method is the reversal of the Parliament's decision precluding the state-run National Health Insurance Fund from reimbursing the purchases of some newly-developed drugs. The reversal came after a heartfelt plea from Borissov despite the fact that just days earlier his GERB party unanimously backed the the same decision.

"Borissov's way of dealing with problems is to put out fires. There will be a government concession in response to every protest, some will come easier, some - harder," says Parvan Simeonov, a sociologist from Gallup International Balkan research agency, adding that in the "advertorial reality" of the EU Presidency, pressure on the government will naturally increase. "He will dissociate himself from different problems and will leave his ministers to handle the damage control; for him it's crucial that people on the streets don't shout his name," adds the sociologist.

As long as opposition forces in parliament (the Socialists) or outside it (the center-right liberal parties) are unable to offer a viable alternative, the three methods of putting out fires will help Borissov stay in power, dashing all hopes for meaningful reforms.

"You have always been decisive and brave. With a Prime Minister who can intimidate any Thracian warrior, you will make it," said the President of the European Council Donald Tusk in plain Bulgarian during his speech for the opening of Bulgaria's turn as rotational president of the Council of the EU. Tusk is not the first politician who praises Boyko Borissov for his dominating physical presence - former UK Prime Minister David Cameron laughingly mentioned once that he needs to recover after a "Boyko hug".

Yet, even a strong man like Borissov, who had managed to lead his GERB party to election victory three times in eight years, has a few soft spots.