National protests have dogged Bulgarian politics recently. They are led by angry miners and energy workers, empowered by the tension between trade unions and the authorities - as in many other parts of the world the diminishing role of coal has triggered state wide dissatisfaction and a big chunk of disinformation. The future of Bulgarian energy has provoked an intense debate about whether coal plants should or should not remain in operation. And the answer is no walk in the park.

Some analysts claim that without coal energy Bulgaria will not have enough electricity, others - that there will be no problem. In the meantime, one argues that the coal energy sector employs 50 to 100 thousand people, while other refers to a number in the region of 10-15 thousand.

The market truth is not easy to swallow: power from the plants is sometimes cheap, but recently it is so expensive that no one gets to buy it. Coal plants can supposedly work by themselves, but they keep requesting state aid due to the high carbon prices that makes their business model bust. As a share of the total electricity production in the country, coal occupied an average of only 32% for the first 9 months of this year, and since June this indicator has been well below the 30 percent mark. This is a far cry from the 50 - 60% floated by various trade unions and political parties. Even in the first nine months of 2022, which saw a real boom in production, thermal power plants generated 47% of total electricity. And in no month of this year, apart from January and February, did their share of production exceed 40%. From afar, one can conclude that when gas is not at a premium, coal literally drops out of the daily production mix.

The weird deal

After five days of protests and blockades on the highways and main arteries, energy workers and their union representatives reached a deal with the government. Those points include mechanisms for financial help, no specific plant closure deadlines, and more money from euro funds.

In essence, however, it is not clear how the agreement will affect the coal sector, as the settlement does not in any way guarantee protesters' important demands, such as the continued employment of miners. And this completely renders the protests and blockades of the last days meaningless and shows that they perhaps were inspired by other motives. The activation of all possible trade unions and populist parties indicates such possibilities as well.

But what exactly are the energy workers and miners protesting about? The debate is being sparked by many people, but actually the answer is not easy at all. When miners blocked the Trakia highway and the Republic Pass on Friday, they demanded that the coal plants and mines not close until 2038 and that their jobs be guaranteed. On the same day, MPs and national tycoons Boyko Borissov and Delyan Peevski confirmed that this would be done and even announced that they would each be paid 36 salaries when they left. Later, Prime Minister Nikolay Denkov also stated that there is no commitment to close specific facilities before 2038 and the state will provide alternative employment for a large part of them in a new state mine recultivation enterprise.

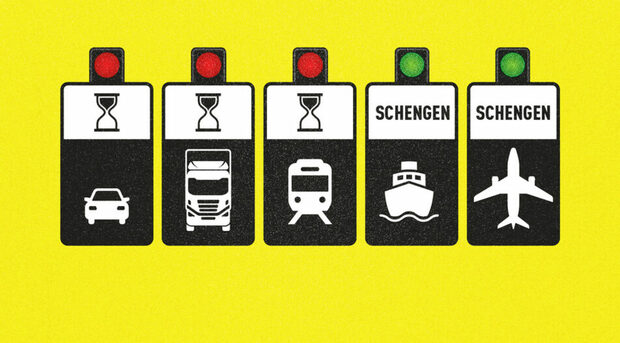

Today, the government published the Territorial Plans for Stara Zagora, Pernik and Kyustendil, which on Saturday it sent to Brussels for approval, and because of which discontent flared up. These are the documents on the basis of which the EC will give Bulgaria BGN 3.5 billion so that the people from the energy sector will not be left out during the reforms. However, they are the same documents that show the affirmation of Bulgaria to decarbonise and transit away from coal facilities in the next few decades. They do not state anywhere that the coal plants and mines must be closed before 2038. There are also no specific requirements for the partial removal of capacities before that date. However, people are convinced that they are the elephant in the room and that Bulgaria's "secret" deal with Brussels is the sole reason for capacities getting kicked out of the market.

The submitted plans are not the issue

In the recent public debates surrounding the miners' and energy workers' protests, a bunch of conflicting data has been exchanged about the role, importance and activity of the coal facilities. This creates real confusion among society and makes it impossible to judge who is wrong and who is right in this dispute.

In fact, the information is public - in the European Organization of Transmission Operators, in which the state ESO is also a member, data is stored for every hour of activity of each plant. And it's easy to see how coal plants contribute to the energy system.

The numbers show the following: in 2023, coal has a record low share of the country's energy mix, electricity exports have literally collapsed, renewable production has doubled, consumption has decreased, and electricity prices have reverted to normal levels.

Looking at the bigger picture, for the last 5 years, coal power plants have had only one successful year - 2022, when due to the immediate shock of the cut Russian gas supplies, there was a crisis with energy prices throughout the whole Europe. Energy prices skyrocketed which was convenient for the expensive coal energy. Or to put it another way - coal plants can only work if electricity is very costly and the revenues cover the costs of wages and carbon emissions (carbon emissions are one of the main reasons why coal electricity is kicked out of the market). There is simply no room for them in the current market conditions when prices are almost back to normal and gas is not extremely overpriced. This is most certainly why comparisons between the usage of coal last year and in the future should be drawn - last year was a fluke that might not ever be repeated.

One of the many reasons why the comparison is untenable is the difference in the average price of electricity. The average price on the exchange has fallen by 59% for the nine months, and proof of the lower prices is that the ceiling adopted by the parliament for subsidizing the business of BGN 200 per MWh was not reached at all in some months.

The fact that coal plants are still operating is mainly due to their regulated market quota, for which they are compensated, so that the final price for residential consumers remains low.

Nevertheless, at certain hours of the day and during winter, the need for coal electricity remains high and without such capacities the energy system would face a serious challenge. That is precisely what no one wants, and why there should be no sudden closure of such plants in the coming years. They will probably be kept as a backup for the system, but they will not have the main player as before.

A miner's future

Bulgaria has no precedent in terms of the energy transition. Such a thing happened in Great Britain decades ago, successfully but not without industrial unrest. Now it is also happening in many places in Europe, and in recent years the transformation is taking place in front of our eyes in Greece. The large coal complex there, an analogue of "Maritsa-east" - "Kozani", already has fading functions and in its place there are huge solar parks, and many of the workers have been redirected to alternative industrial enterprises. At the same time, the plan for the development of the region, with money from the same territorial plans against which the Bulgarian energy workers are protesting, continues and no one there is heard to complain. Of course, Greece has reserved certain coal capacities, which it uses when needed and with which it guarantees its security - something that Bulgaria also clearly says it wants to do, but the sector seems to prefer not to hear.

And in the debate about jobs, the issue of air pollution and the environment in general is somehow forgotten. The region around Radnevo and Galabovo has a record number of lung diseases per capita, especially among children. In general, dust in the surrounding area is high, often excessive. The black smoke from plants like Brickell can be seen for miles, and the suffocating smell hangs everywhere. People's health, in addition to directly affecting themselves, also has a large effect on the economy - more sickness means a reduced labor force and higher health care costs.

National protests have dogged Bulgarian politics recently. They are led by angry miners and energy workers, empowered by the tension between trade unions and the authorities - as in many other parts of the world the diminishing role of coal has triggered state wide dissatisfaction and a big chunk of disinformation. The future of Bulgarian energy has provoked an intense debate about whether coal plants should or should not remain in operation. And the answer is no walk in the park.

Some analysts claim that without coal energy Bulgaria will not have enough electricity, others - that there will be no problem. In the meantime, one argues that the coal energy sector employs 50 to 100 thousand people, while other refers to a number in the region of 10-15 thousand.