As Kenneth Rogoff, an economics professor at Harvard defines it, the debt spiral has four phases: rising debt, rising cost of borrowings, spending cuts and/or tax increases, slowing economic growth and once again rising debt . Is Bulgaria already dancing this fatal dance?

Let us look at each of the four phases to try to find the answer.

Rising debt

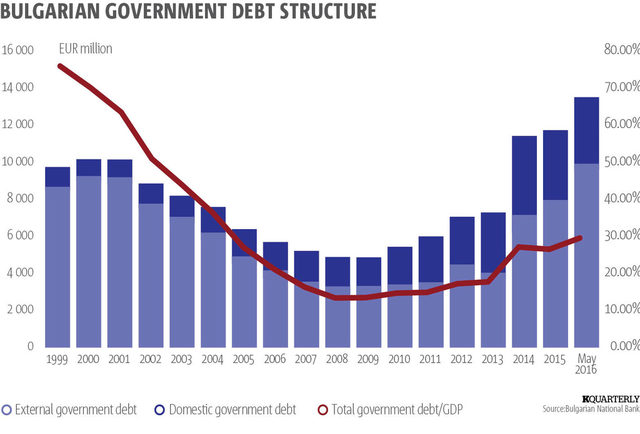

Over the past 17 years government debt has dramatically declined. It reached its minimum in absolute dimension in 2009 at EUR 4,828 million, while the minimum in relative terms was registered in 2008 when the government debt stood at 13.30% of GDP. After 2009 government debt has grown at an average annual rate of 17% on year-to-year basis. That is quite disturbing and in fact this is the reason to ask whether the country goes into a debt spiral.

Driven by permanent budget deficits from 2009 on, government debt has more than doubled as share of GDP between 2009 and 2016 from around 13.40% to 29.30%. Even though it is still relatively low compared to EU peers, this ratio will inevitably increase in the coming years if fiscal consolidation proves difficult to implement or in case further funding is needed by the financial sector or some sectors of the real economy. At the same time the financing needs of the government are constantly increasing, making deficit reduction а difficult task. Furthermore, the growing size of contingent liabilities related to state-owned enterprises, most notably in energy and transportation sector, are definitely a risk factor for the national economy.

Debt servicing has not been significantly affected because of the favorable financing conditions created by the low-interest-rate environment in the last few years. However, the situation can change in the medium term. An additional risk factor is the growth of contingent liabilities related to state-owned enterprises, most notably in energy and transport.

Another noticeable trend is that the government has been steadily changing the ratio between domestic and external borrowing. From 1999 to 2009 domestic debt was on average some 20% of the total government borrowing, increasing from 9% to 32%, while in the period 2010-2016 it is on average 37%, but declining from 45% to 26%. This probably indicates that when debt is rising, the lending capacity of the domestic market (especially in local currency) is easily exhausted. The figures once again demonstrate the fact that being a small open economy, Bulgaria strongly depends on international capital markets and IFIs.

Rising cost of borrowing

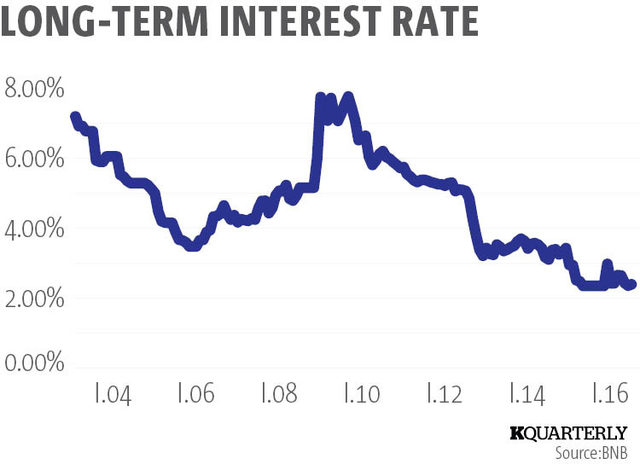

The next three charts illustrate the changes in the cost of borrowing for the Bulgarian government. The long-term interest rate for convergence assessment purposes (see chart 2) is determined on the basis of the secondary market yield to maturity of a long-term bond (benchmark) issued by the Ministry of Finance and denominated in national currency.

It has been influenced over the past five years by the ever increasing (lately even excessive) liquidity on the domestic banking market, not so much by concerns of increasing government debt. Simply local banks and pension funds are hungry for government bonds due to lack of alternatives similar in risk profile.

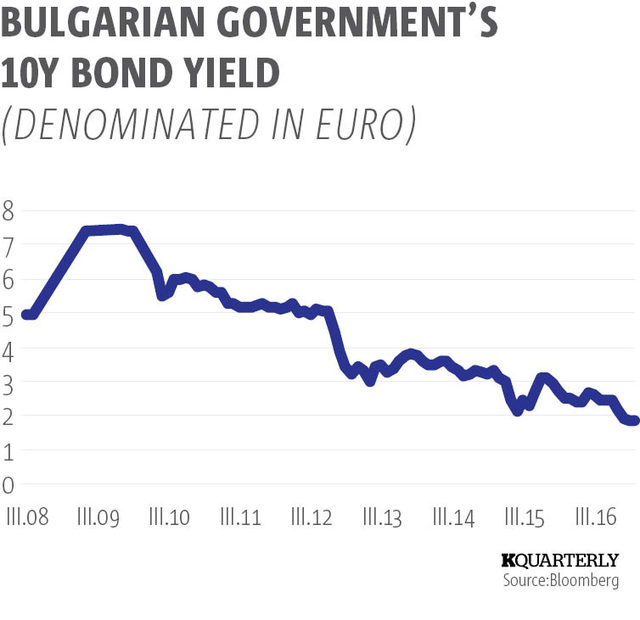

The next chart (chart 3) shows the yield of the benchmark 10-year Bulgarian government bond denominated in euro. It shows the positive effect of the global low-interest-rate environment in the last few years.

Clearly, with the exception of Croatia, Hungary, Slovakia, Czech Republic, Poland and even Romania "outperform" Bulgaria after mid-2014 when the fourth largest Bulgarian bank collapsed, increasing concerns about the soundness and resilience of the country's banking sector. Investors' concerns about Bulgaria are still not so much driven by the level of public debt but by the sectors which need structural reforms like energy and transport. There are sizable liabilities of state-owned companies in these sectors, which may produce one-off financing needs that will have be covered by the government.

Spending cuts and/or tax increases

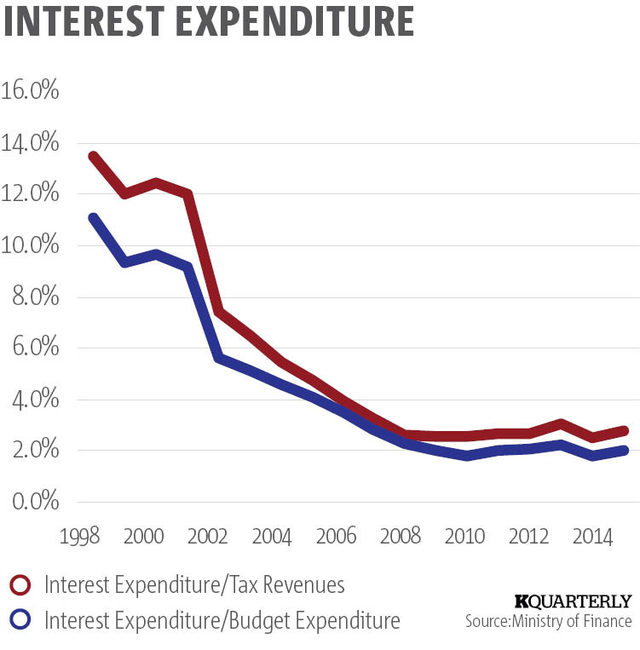

Interest expenditure of the government budget is still rather moderate. Therefore, it does not motivate the government to cut spending or increase taxes (Chart 4 chart illustrates the evolution of interest expenditure for the period 1999-2015).

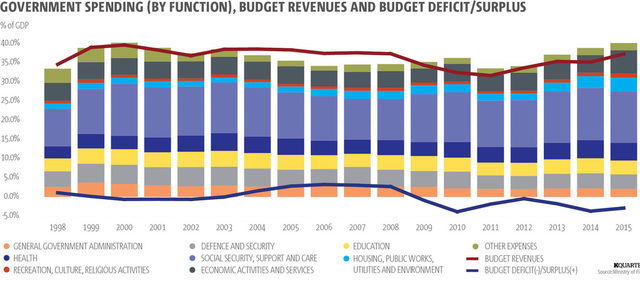

The next chart (Chart 5) shows the government spending and respectively the budget revenues and budget deficit/surplus for the period 1999-2015.

The chart clearly visualizes the lack of specific effort by the government to achieve fiscal consolidation after 2008. Fiscal consolidation means a robust policy aimed at reducing budget deficit and debt accumulation. The most efficient way of doing this is to optimize and eventually cut government spending. Several consecutive governments have missed the opportunity to introduce much-needed reforms in the education system, healthcare, the social security system and the labor market.

Reforms are also crucially needed in the financial sector, mainly regarding the quality of supervision of the banks and pension funds. The financial sector is still perceived as a potential source of risks for the overall stability of the country.

The state-owned companies in the energy sector (and to a lesser extent in the transport sector) have generated substantial amount of liabilities, which may require a shift in government spending or may lead to an increase in budget deficit.

The government has slightly improved the efficiency of tax collection but still there are significant opportunities for better tax revenues, as the effort of the government has so far been rather opportunistic, but not systematic.

In general, there is no severe necessity for imminent spending cuts but implementing immediate and radical reforms is a necessity.

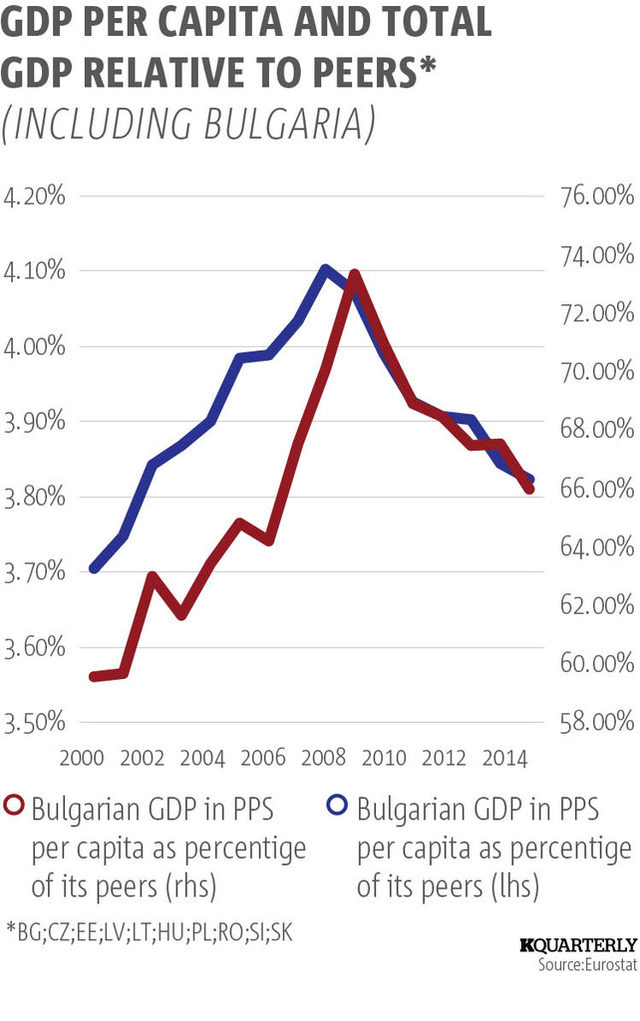

In its last country report on Bulgaria the European Commission makes the following comment about the country's economic growth: The recovery has not so far been strong enough to support economic convergence with regional peers. Compared with peer economies, Bulgaria has significantly underperformed since the outbreak of the crisis in terms of both GDP growth and GDP per capita (Graph 6).

The economic growth post crisis has been export-driven, which is rather healthy, but there are several structural constraints for the country to reveal its potential.

Among the most important ones are the business and administrative environment and the related problems with the rule of law, the human capital i.e. the labour market (rapid population ageing, substantial outward migration, skills shortages and mismatches), the education, social security and healthcare systems, the level of corporate debt.

An advisable fiscal consolidation may lower economic growth in the short term, but if it comes as a result of much needed reforms it will help the country in the long term. The level of government debt is not threatening economic growth in the short term, but the lack of adequate reforms jeopardises the mid- to long-term perspectives of Bulgaria.

To sum it up, Bulgaria is clearly not yet in a debt spiral, but the lack of structural reforms will take the country there sooner rather than later.

* Yordan Yordanov is a Managing Partner of Optimum Consilium OOD, an independent investment and financial advisory company.

As Kenneth Rogoff, an economics professor at Harvard defines it, the debt spiral has four phases: rising debt, rising cost of borrowings, spending cuts and/or tax increases, slowing economic growth and once again rising debt . Is Bulgaria already dancing this fatal dance?

Let us look at each of the four phases to try to find the answer.