We were once fourth in the world. No, we're not referring to the legendary performance of the Bulgarian national football team in the 1994 World Cup, but about something much more pedestrian and invisible to the eye, yet quite significant. Fixed internet connection in Bulgaria used to be one of the national prides of the early XXI century, but can hardly be counted as such anymore. Not because the internet in Bulgaria is slow or particularly expensive, but because in the last decade it has slowly sunk from one of the best networks in the world to being so mediocre.

There are many explanations for this change, but there are at least three key ones - the market is much more concentrated and there are two giant operators - BTC (Vivacom) and A1; the demand for really fast connection is not high; and investment in networks for urban areas is difficult and expensive. Additionally, the alternative offered by cheap, easily accessible mobile internet, which also brings in more revenue, hit the broadband market. According to the latest figures of the Communication Regulation Commission (CRC), consumers paid 1 bln. BGN for internet in 2020, of which just over 300 mln. BGN went on a fixed connection.

We started from the top and now we are here

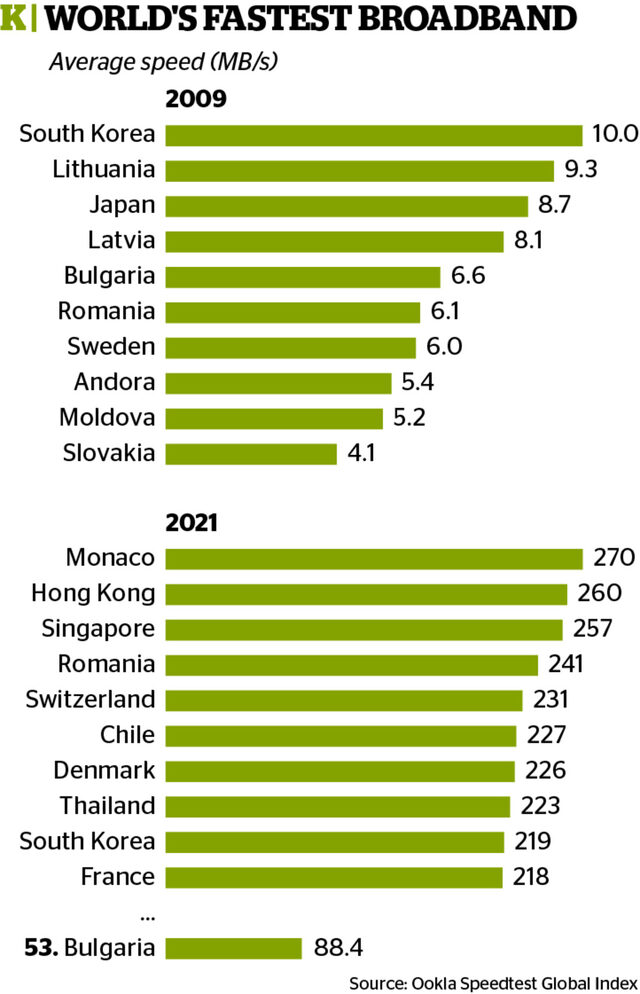

In 2009, Bulgaria ranked fourth in Ookla's ranking of the fastest fixed internet in the world. At the time, the country was ahead of South Korea, Japan and Lithuania, with neighboring Romania just behind. One decade and two waves of consolidation in the provider sector later, Sofia has dropped to 53rd place out of 181 countries. None of the top five countries - bar Romania - remains in the top five list from 2009.

This does not mean that the internet in Bulgaria has become slower, quite the opposite. In 2009, the average speed was around 7 megabits per second, while in 2021 it went up to 88 megabits per second. At the same time, however, other countries have moved at a faster pace. For comparison, the average speed of Internet in Romania is three times higher today, at 241 megabits per second, not too far from the first in the ranking - Monaco, where the speed is 270 megabits.

It is also important to note that, when it comes to mobile internet, Bulgaria is in the top 10 not only in Europe, but worldwide. In fact, part of the explanation for the slowdown in broadband connection speeds hides precisely here - over the last ten years, the country's telecoms have prioritised their mobile network at the expense of their fixed network.

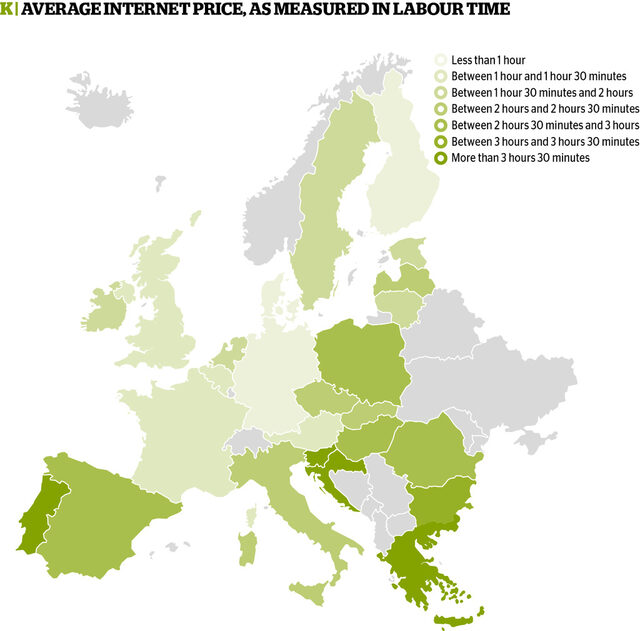

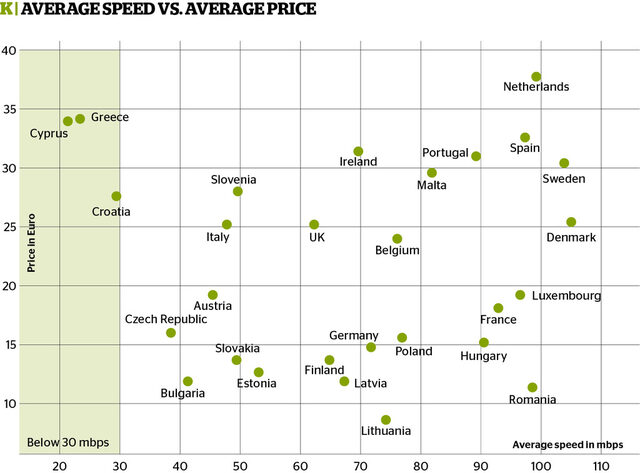

At the same time, the price for fixed internet in Romania is lower than in Bulgaria. This does not make the internet in Bulgaria especially expensive - according to the European Digital Compass, it takes 3 hours and 22 minutes of work to pay the average internet bill in Bulgaria for someone earning an average salary. In Romania they would pay it off for 2 hours and 43 minutes of work per month. The champion is Finland, where the internet "costs" 44 minutes per month per person. Naturally, in nominal terms, Bulgaria tops the list for cheap internet. However, the trend in coming years is one of growing prices.

The story in short

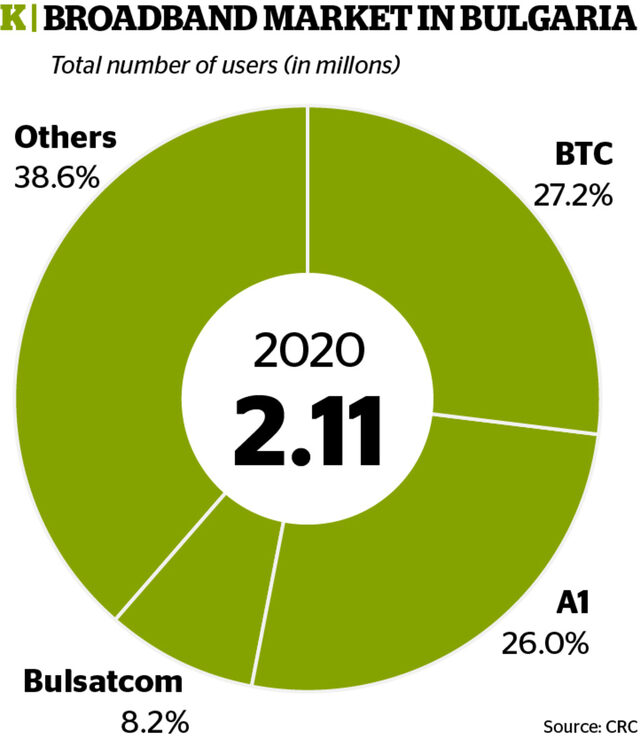

At least on paper, competition has not declined sharply - according to the CRC, the number of retail internet providers is as high as in the last few years - around 650, but at the turn of the century there were over 2000. At the same time, the shares and influence of the two main players, BTC and A1 Bulgaria, are growing (see the charts). With the recent acquisition deals of the former state telecom, the two operators will be holding over 60 percent of the market.

Those involved in the internet business in Bulgaria over the past 20 years have different takes on why the country is no longer the leader in fixed internet. At the same time, the big telecoms - BTC and A1 Bulgaria - which have dominated the market for the last ten years and will be an unassailable factor in the coming years, have significantly different views from those of the internet pioneers.

Some paint a brighter picture, while others don't see how two giants can innovate in a market without much room to gain market share outside of acquisitions. For most, the second wave of consolidation, as BTC's series of purchases of relatively large regional providers such as ComNet, Networks (which also owns Sofia's Online Direct), Net1, Plovdiv's N3 and Telnet from Veliko Tarnovo (announced in early December), will further slow the market's development. Others believe that the big players are the only ones with the financial capacity to introduce mass access to fast fibre-optic internet in the country. To understand these discrepancies of opinions, one needs to look back at the history of the internet in Bulgaria.

Wild West years for internet

The development of the Internet in Bulgaria began in the mid-1990s. Back then the picture was radically different - the telecoms had no interest in fixed internet, BTC was still state-owned and mostly dealt with home telephony, and Bulgaria's total connectivity was measured in kilobits. Several young companies took on this problem. Some of the key players in this process used to be Orbitel, Megalan and Spectrum Net.

All three eventually ended up as part of A1 Bulgaria (then Mobiltel), which in 2010 bought Megalan and Spectrum for 72 million euro, which is impressive even by today's standards. In 2005, Deutsche Telekom, through its Hungarian unit Magyar Telekom, bought Orbitel only to resell it in 2008 back to Bulgarian-owned Spectrum. Then came the big merger of Mobiltel with Blizoo, completing the first wave of consolidation around one of the big telecom players.

The technical story is considerably more convoluted. In the late 1990s and early 2000s, providers had a number of problems, but the biggest two were: bringing the internet in from outside and cabling in the urban areas. The first was solved by the import of internet by BTC, Netera and others, and subsequently the major international internet exchanges such as those in Amsterdam and Frankfurt made wholesale internet available to any neighborhood provider.

The cable problem was much bigger. Infrastructure, especially the underground network, was owned by the state-owned BTC, which zealously guarded its monopoly. Orbitel, Megalan and Spectrum wanted to deliver significantly faster internet, but burying the cables has always been expensive for small providers. Then the cabinet of Simeon II (2001-2005) made the best move for Bulgaria's connectivity - it turned a blind eye and declared an unofficial "regulatory holiday".

This is how the "cables in the trees" phenomenon that Eastern Europe became famous for appeared. It worked, and in a few years the big cities were connected to the internet of a quality that even the most developed countries could envy. Eventually the "regulatory holiday" ended but small providers were no longer so small and could afford tucking cables underground. Then the first wave of consolidation took place as telecoms realised voice services were no longer the only viable revenue stream and they turned to the internet market. Gradually, three big players emerged - A1 Bulgaria, BTC and Bulsatcom, capturing more than half the market.

A Natural Monopoly

"The telecom sector, like it or not, is a natural monopoly. It tends to monopolize because there is an economy of scale and that means it will always seek scale. If it stops growing organically, it starts buying," says Nikolay Gorchilov, co-founder of Orbitel and subsequently of Indian telecom Excitel. In his view, what has happened and is happening in Bulgaria follows the logical path of a developed market that has reached its ceiling - the big are buying the small to cut costs.

This business logic gave birth to the long-term contracts that have emerged in the last ten years. At one point, telecoms could offer TV, voice, mobile connectivity and fixed internet. And because the hardest part for all companies in any of these sectors is attracting and retaining customers, these services were bundled into long-term contracts at promotional prices. Among other things, they make measuring the cost of the Internet in Bulgaria a difficult task. BTC, for example, offers gigabit internet for around BGN 40 per month, but only with a promotional two-year contract. If it is a one-year contract, the price is between 100 and 150 BGN per month.

According to Gorchilov, in India a gigabit package would cost around 15-20 BGN and "there is no technical reason" why this should not be the case in Bulgaria. "However, when your market is small and the goal is to make more revenue next year, the profit comes from raising prices."

During his conversation with Capital, he gives a few more reasons for the lagging internet in Bulgaria. First, most people use the internet over a Wi-Fi network, and its speed depends on the quality of the router and which frequency users are tethered to. Second, a large proportion of customers are still connected via copper cables rather than fibre connectivity - a problem that telecoms are trying to solve, as it also offers revenue growth potential. And third, and most important of all, demand for faster internet is largely non-existent.

"It's got to a level where we've got good internet, everyone's happy and nobody cares if there's a better offer; they're not looking for better internet. The telecoms have no motivation to invest in new technology, there's no real competition between them, and customers are not unhappy, because the fact is that even at 30 or 50 megabits, speed it's still okay. Will it work for me in the future? Not really. Does it work for me today? Well, it does the job," Gorchilov concludes.

or state-nurtured oligopoly

Neven Dilkov, another internet pioneer, sees things differently. Netera, the company he founded, provides wholesale internet services, which gives him an overview of the market in Bulgaria. Dilkov told Capital that he finds the situation in Bulgaria worrying. "From 1996 to 2014 - that's 18 years - Bulgaria was on top. And then the consolidation happened. In all business circles these are normal processes when the market matures. But in such a situation a healthy state and government become active. In the beginning, everyone was left to do what they wanted, but when a market becomes fragmented, the level of competition decreases and you need regulation to ensure a level playing field," he says.

In Bulgaria, he adds, when regulations have emerged, they have been aimed at preserving or expanding the market share of the big players, not at providing everyone a level playing field. "There is not a single decision of either the Competition watchdog (CPC) or the CRC that seeks to preserve the diversity on the market, to protect the rights of big and small companies alike. Small providers have started to simply give up. The more serious firms that remained could be counted on the fingers of the two hands. The rest either disappeared or started working in the gray sector," Dilkov says.

Optimistic telecoms

The pessimism of the pioneers clashes with the optimism of the telecoms. They do not deny that there is a problem with the network, claiming that the modernization of internet provision in Bulgaria will take time and hundreds of millions of euros of investments. At the same time, they point out that this can only happen in a market where there are big players."We think that a market with 600 small providers is a market where you won't see much innovation and investment," Zeljko Batistić, vice president of technology at United Group, the company that owns BTC, and the new technical director of the Bulgarian company, told Capital. Batistić is one of the driving forces behind United Group's approach to achieving growth through acquisitions.

He agrees that Bulgaria has a connectivity problem, but he believes the answer lies in telecoms competing in the fixed network as they do in the mobile network. "When we came in a year ago, we made a plan to invest significant amounts in 10G technology, new 10-gigabit networks in a strategic partnership with Nokia. We have already started with the network build-out and have covered 240 thousand households with this technology. The plan is to cover 1.7 million households in the next five years. All of them will be able to develop speeds of 1 gigabit or more," he says.

Batistić says that 300 million euros will be invested in BTC's fixed network alone over the next five years. A significant portion of that money will go to the most expensive part of the business - the so-called "last mile," or the final cable that connects the main network with the home of the customer. At the moment, a large proportion of users rely on copper cables that provide limited connectivity speed and switching to fiber is expensive.

After the big deals of 2020-2021, it appears that the consolidation on the market might be coming to an end. According to CRC data, BTC holds the largest portion of the market as of 2020 with 27.2 percent of customers, followed by A1 Bulgaria with 26 percent. However, this does not include BTC's new acquisitions. With them, the company would have about 35 percent market share, Capital's calculations show. Batistich predicts that a third mobile operator, Telenor, will also enter the fixed internet market. Currently, the role of "third player" is played by Bulsatcom, which, however, relies mainly on TV provision and does not prioritize Internet delivery. The company holds 8.2% of the market with around 170,000 users as of 2020.

The other big player, A1 Bulgaria, claims to have invested more than 30 million BGN in its fixed line this year alone. "Nearly 40% of our subscribers use fibre-optic internet," the operator's CTO Todor Tashev told Capital. According to him, mobile network investments amount to another 100 million BGN.

In fact, the biggest investments in the coming years will be in the mobile network and the rollout of 5G connectivity, where the expectations are for value addition and the opportunity for more revenues. The two are linked because the 5G network is fed through fiber optic cables. The investment is visible through global mobile network rankings, where Bulgaria is in the top 10.

It is unlikely that Bulgarian home internet would ever again fall into the "national pride" category. The most likely scenario is that this niche will remain entirely the territory of the big telecoms. They have the financial ability to roll out high-speed networks and take on the burden of the last mile, but along with that customers can expect higher prices. As long as there is no demand for faster internet from these same customers, the chances of higher speeds coming soon will remain low.

Konstantin Nikolov contributed to this piece

The development of fixed internet in Romania is very similar to that in Bulgaria - except for the outcome. In the 1990s, there was almost no internet in Romania. From then on, a huge number of local providers and networks started to emerge, making it easy to share pirated movies, music and games. Eventually, some of these self-contained networks transitioned into real ISPs. Competition, neighborhood-level scale, and anarchic expanses of cable did not affect urban aesthetics or copyright royalties so much, but they certainly played a role in the rapid development of high-speed Internet. Then, some level of consolidation took place, but far from the near-oligopoly that formed in Bulgaria. As we speak, there are still many competitive local-level providers working on district level in Romania. Judging by the average internet speed, which puts to shame many more developed Western countries, the effect from this for the country is a net positive.

We were once fourth in the world. No, we're not referring to the legendary performance of the Bulgarian national football team in the 1994 World Cup, but about something much more pedestrian and invisible to the eye, yet quite significant. Fixed internet connection in Bulgaria used to be one of the national prides of the early XXI century, but can hardly be counted as such anymore. Not because the internet in Bulgaria is slow or particularly expensive, but because in the last decade it has slowly sunk from one of the best networks in the world to being so mediocre.

There are many explanations for this change, but there are at least three key ones - the market is much more concentrated and there are two giant operators - BTC (Vivacom) and A1; the demand for really fast connection is not high; and investment in networks for urban areas is difficult and expensive. Additionally, the alternative offered by cheap, easily accessible mobile internet, which also brings in more revenue, hit the broadband market. According to the latest figures of the Communication Regulation Commission (CRC), consumers paid 1 bln. BGN for internet in 2020, of which just over 300 mln. BGN went on a fixed connection.