Shepherds are a disappearing breed in modern Bulgaria, and pasture animal husbandry is losing popularity for a number of reasons - it is difficult, not especially viable financially and unattractive to younger generations. If a cattle breeder makes the news, it's unlikely to be for a good reason. The recent case of the brothers Sider and Atila Sedefchevi from the village of Vlahi in Kresna illustrates this all too clearly. The brothers, who breed Karakachan sheep and dogs, were evicted by the municipal council because their animals disrupted the villagers - even though the village has only 4 inhabitants!

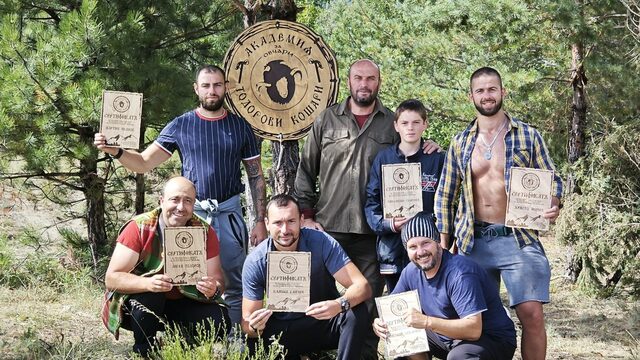

Recently, however, another story about shepherds - this time a positive and inspiring one - caught the media's eye. In August, Todor Georgiev's Po Todorovi koshari farm, also near Kresna, organized the first Shepherds' Academy in Bulgaria. Up in the high mountain pastures of Pirin, 20 or so enthusiasts were trained in the ins and outs of high mountain grazing along with several hundred Karakachan sheep and goats for 10 days.

This is not exactly a team building activity: the conditions in the mountains are difficult - heat, insects, dust, and sometimes heavy rain. The work is physically demanding. However, the interest in the initiative is great - so much so that Po Todorovi koshari is preparing a second edition in the second half of November, and their plans are to have a course every season.

From yogurt to an academy

Todor is a hereditary cattle breeder from Kresna. The farm belonged to his grandfather, who raised one of the last large highland herds before collectivization at the beginning of socialism. Subsequently, his father, and then he and his brothers, still managed to keep the farm afloat, albeit on a much smaller scale. In recent years, Todor has managed to increase and restore the family herd to nearly 1,000 Karakachan sheep and long-haired kamenarki mountain goats - descendants of the Karakachan goats, which are very well adapted to the rocky terrain of the Pirin Mountains.

He is an ecologist by education, having graduated in Ecology and Environmental Protection at the South-Western University and also works as the chief specialist Control and Security in the Pirin National Park. However, animal husbandry is in his blood. "I grew up with this heritage - the animals, the barns up in the mountains. It is extremely valuable to me and I want to preserve and protect it," says Todor. He adds that he has long considered how to popularize this type of animal husbandry, because he believes that there are people in Bulgaria who "carry sheep breeding in their genes".

The impetus for the creation of the Academy came after he and his wife decided to register as small dairy producers. They had been making milk and cheese for a long time - mainly for home needs and for friends. Over time, however, interest in high-quality dairy products from grazing animals has grown. "Many people started wanting to buy milk and cheese from us, and we were unable to cope with the family production. That's why we decided to make a small dairy," says Todor.

Pure artisanal food as a solution for small farmers

Todor Georgiev's farm, like others, receives European subsidies under some of the schemes of the Common Agricultural Policy of the EU. They are, of course, helpful and over the years have been among the factors that have helped him rebuild the herds. But he believes that the way to upgrade the activity and to have an incentive for small farms to be sustainable and to multiply is to close the cycle with the production of clean, artisanal and traditional products. "There is already a demand for such genuine and quality foods today, especially in Sofia and the bigger cities. People are starting to appreciate them," he says.

Thus, he sees a future for development in the promotion of high-quality traditional products. "If people start looking for clean and quality food, to think about their health - especially for children, this will help farms like ours a lot", believes Georgiev. He believes that the efforts of farming communities should also be directed there, and the media can also play a role in popularization. But the administration could also help with more targeted financial support for such farmers, as well as some easing of the complex rules, which Georgiev says would enable small producers of traditional foods to survive.

For the establishment of the dairy farm, he turned to business consultant Angel Todorov for expert help, since the work on the farm has become too much for one family. "Angel came up with the idea of putting out a call for helpers in the farm - something like interns. It turned out that there was interest, and like-minded people gathered. From there, the idea evolved into the Shepherds Academy," shares Todor.

The wild is calling

The promotion of the initiative takes place through a Facebook page that his wife is preparing. In the beginning, the idea was shared without much noise in a relatively narrow circle, but it turned out that there was more interest and in a short time many people gathered. The group of about twenty filled up quickly. "The goal was to gather people who would both help us and learn the craft and preserve the tradition," says Todor.

The volunteers are mostly young men, some of whom come with their children. According to the owner of the farm, most of them are urban people, young, well-educated, with careers in various spheres of the economy - IT specialists, entrepreneurs, managers. "For some, the motivation must have been to escape from the monotony of city life for a while. For others, the idea of the mountains, the herds, and the wild seemed somewhat romantic - a kind of call from the past. In any case, what united the men was that everyone had the right attitude - attitude to the land, to traditions, to clean food," says Todor.

The August training took place in a summer barn high in the mountains. Work would start at 6:00 a.m. and last until 10:00 p.m. It included turning the animals out to graze, milking, maintaining and building new pens and outbuildings, and any other day-to-day activities that accompany the work of a pastoralist.

Todor has no illusions that all the students will choose this life, but he hopes that at least one of them will someday decide to have their own farm and become an animal breeder, although it is a very difficult profession, he says. However, the interest in the Shepherds' Academy still shows that there is hope that small-scale mountain farming will be an attractive livelihood again one day. And Do Todorovi koshari plans to hold such trainings every season - spring, summer, autumn and winter.

Shepherds are a disappearing breed in modern Bulgaria, and pasture animal husbandry is losing popularity for a number of reasons - it is difficult, not especially viable financially and unattractive to younger generations. If a cattle breeder makes the news, it's unlikely to be for a good reason. The recent case of the brothers Sider and Atila Sedefchevi from the village of Vlahi in Kresna illustrates this all too clearly. The brothers, who breed Karakachan sheep and dogs, were evicted by the municipal council because their animals disrupted the villagers - even though the village has only 4 inhabitants!

Recently, however, another story about shepherds - this time a positive and inspiring one - caught the media's eye. In August, Todor Georgiev's Po Todorovi koshari farm, also near Kresna, organized the first Shepherds' Academy in Bulgaria. Up in the high mountain pastures of Pirin, 20 or so enthusiasts were trained in the ins and outs of high mountain grazing along with several hundred Karakachan sheep and goats for 10 days.