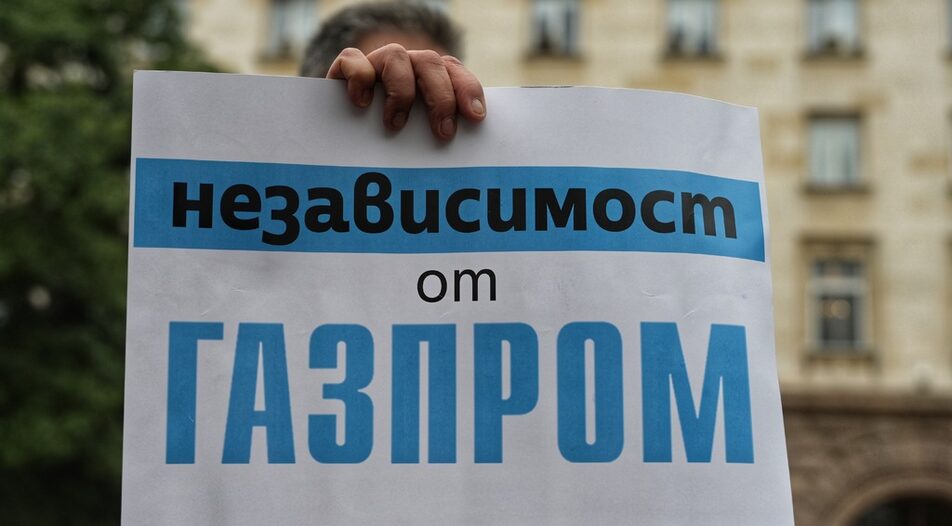

Thanks to its recent actions and statements regarding potentially resuming relations with Gazprom, the caretaker cabinet of PM Galab Donev risks weakening Bulgaria's position in a possible arbitration case. Even worse, it is, in effect, helping Russia. One of the biggest risks in reverting to Russia-supplied gas through accepting all Moscow's conditions, including payment in rubles, is that it gives Gazprom a stronger argument that it is Sofia and not Moscow who is failing to fulfill their part of the contract.

This is no longer about whether there will be gas in the winter, its cost and supplier - but rather about protecting Bulgaria's national interest. The caretaker government's avowed intention to beg Gazprom to resume Russian gas supplies could land Bulgaria in a 1.8 billion financial trap - or more than twice what Bulgaria paid after the Belene NPP arbitration, which was lost because of political (mis)steps.

The Gazprom contract's terms

Bulgargaz's current contract with Gazprom Export, which expires at the end of this year, is for 3 bcm/year (approximately 100 percent of the country's annual gas needs) and has a take-or-pay clause, which is generally mandatory for any long-term contract in the gas sector.

"We must use 80 percent of the volumes requested under the contract with Gazprom," caretaker Energy Minister Rossen Hristov said last week, adding that the agreement with the Russian side provides for upward or downward discrepancies of up to 20 percent of these volumes. Calculations show that this equates to 2.4 bcm. Of these, in Mr Hristov's own words, Bulgaria had used roughly 1 bcm before the 27 April supply cut, which means that there are still 1.4 bcm left for the year. Sofia could be forced to pay for them, despite not receiving or using them. With average gas prices from Gazprom export since April of around 125 euro per MWh, this would amount to 1.8 billion euro of foregone benefits for the Russian company. With rising prices on the TTF index, the amount could even exceed this by the end of the year.

Of course, whether Bulgaria has to pay or not will be decided in an arbitration case in Paris, as per the treaty. So far, Sofia's stance has been that Bulgargaz is strictly fulfilling its contract by making requests and transferring the relevant dollar amounts to the account specified in the contract with Gazprom Export, while the Russian side is violating the agreement by returning the money and refusing deliveries.

The Bulgarian self-sabotage

Unfortunately, in the past few weeks, representatives of the Bulgarian cabinet - and especially Energy Minister Hristov, repeatedly claimed that Bulgaria has little chance of winning an arbitration if all other countries have accepted Moscow's payment method and heeded Gazprom's new demands. He referred to Germany, France and Greece. However, if Bulgaria accepts the ruble-denominated mechanism, it will single-handedly ruin its own chances of winning the case altogether, as it will delegitimize its own decision not to accept the treaty change imposed by Russian President Vladimir Putin's decree in April. Then Moscow unilaterally insisted that payments would be made under a new mechanism and returned the payment to the Bulgarian side in dollars, as per the contract.

Energy expert Kaloyan Staykov cited two other points that give Bulgaria an advantage in the arbitration: "In its letter, Gazprom Export explains that it cannot meet its gas supply obligations due to force majeure. If there are such circumstances, can the same company demand penalties or claim non-performance of the contract by its counterparty, Bulgargaz, because it has not paid for the quantities that Gazprom Export admits it cannot deliver?" Mr Staykov asks rhetorically.

"According to the legal analysis of the implications of the new contract payment terms, commissioned by Bulgargaz, it says they are not risk-free. Is it then reasonable to agree to them without any ambiguity, or should we negotiate, or should we automatically cut off all communication?" he adds.

Russian gas - cheap or expensive?

This is not the only problematic statement made by caretaker minister Hristov: 'We need gas at the lowest possible price. According to the contract we have now with Gazprom Export, the price of gas we would get is close to that of Azeri gas".This is not true. It was not even true two or three months ago, when Russian supplies were at around 80-90 euro/MWh. After June, due to limited supplies to Germany and Central Europe, gas prices (TTF) shot up sharply and passed 200 euro/MWh in early August. In the last 10 days alone there has been another 50 percent increase to over 300 euro/MWh. And it is the TTF index of the Dutch exchange that is the basis of the Russian gas formula (with a 70 percent weight in the price formation). So when it goes up, Russian gas for Bulgaria goes up with it.

Thus, if the price in August is taken into account, the gas under the contract with Gazprom would be 186 euro/MWh. At the same time, Azeri gas is oil-indexed and depends on the oil price in the last 6 or 9 months, so it is almost unchanged.

The price of the seven US Chanier Energy tankers that have been contracted, of which only one will be unloaded in October, is 175 euro/MWh. This means that a serious chance was missed to secure cheaper gas for the winter - as far back as July. While it may have seemed more expensive then than Russian gas, the situation is radically different now that the TTF prices are up. And by U-turning on Gazprom now, the caretaker government is actually leading Bulgaria into a second trap - in addition to losing the arbitration trump card, the country will also pay more for its gas supplies.

Continued payments to Gazprom lead to another problem - the unpredictability of supply. A number of private companies from European countries pay according to the Kremlin's mechanism, but they receive only a fraction of what they are entitled to, and Gazprom is constantly coming up with new excuses for why the fuel is not reaching European counterparts. The main reason is that Russia is using Gazprom as a financial weapon, knowing that the major European economies have no choice - the suspension of deliveries via the Nord Stream - 1 pipeline is a case in point.

However, Mr Hristov also said that "if Bulgaria does not get optimal conditions for itself, we will not continue working with Gazprom. We won't agree at just any price. We have already secured most of the gas needed for October. We will provide the rest. We have somewhere to buy gas from, the question is the price," he said in a recent interview. Slowly, at the beginning of September, various other advocates of continued negotiations with Gazprom, including ex-PM Boyko Borissov and industrialist Kiril Domuschiev, also changed their tune, which had been ostensibly pro-Gazprom.

The big question is if the caretaker cabinet's double whammy - weakening Bulgaria's arbitration claims and killing off the possibility of (relatively) cheaper LNG deliveries in the summer - hasn't already derailed the country's bid to secure gas supplies.

Thanks to its recent actions and statements regarding potentially resuming relations with Gazprom, the caretaker cabinet of PM Galab Donev risks weakening Bulgaria's position in a possible arbitration case. Even worse, it is, in effect, helping Russia. One of the biggest risks in reverting to Russia-supplied gas through accepting all Moscow's conditions, including payment in rubles, is that it gives Gazprom a stronger argument that it is Sofia and not Moscow who is failing to fulfill their part of the contract.

This is no longer about whether there will be gas in the winter, its cost and supplier - but rather about protecting Bulgaria's national interest. The caretaker government's avowed intention to beg Gazprom to resume Russian gas supplies could land Bulgaria in a 1.8 billion financial trap - or more than twice what Bulgaria paid after the Belene NPP arbitration, which was lost because of political (mis)steps.