Over the past three months, Bulgaria opened its doors to more than 100,000 refugees from Ukraine - an unprecedented inflow for the country, at least in the last century. Those fleeing the war have encountered invaluable support from tens of thousands of volunteering Bulgarians who have offered them food, care and a shelter. Yet others have also faced hostility that included (in two cases) sticking a pickaxe in the bonnet of their cars. The state and business, on the other hand, took a pragmatic approach - hoteliers hosted 60,000 people in the (formerly) empty Black Sea holiday sites while the state picked up the tab.

On the cusp of the summer season, however, the situation is very different. War is war, but tourism is money, say hoteliers, who want to exploit their properties' potential to the hilt after a series of difficult summers. Now the ball has been passed back to the state, which must find new shelter for tens of thousands of people, organize their relocation, and support and encourage their integration into the labor market. The scale of the task at hand is enormous and time is running out - the current accommodation program expires on 31 May and some seaside hotels that are already taking tourists are getting increasingly nervous.

From conversations between the KInsights team and members of administration it appeared that there is an obvious willingness to act. Yet signs are also that capacity to do so is insufficient, while organization is rather chaotic and fluid - data is being collected from refugees, with possible relocation spots being specified and transport arranged at the last moment. Days before the deadline, it was still unclear exactly how tens of thousands of people would be relocated, what are the conditions of the institution-owned holiday homes that will be used for accommodation and where are they located. The latter is also important for the refugees' employment prospects - jobs will be hard to come by in remote holiday homes, for example.

Many signs were pointing to all this and the administration should have sprung into action much earlier. Preparations should have started long ago. Only continued interest in receiving a (more modest) state subsidy for hosting refugees, expressed by some hoteliers, as well as the trend of some refugees returning to Ukraine, is saving the operation from meltdown. Fact is, state holiday homes can - at best - accept no more than half of all the refugees from seaside hotels. Moreover, it is not entirely clear whether all of these state-owned accommodations are fit to host people in normal conditions.

The current plight of the refugees once again highlights the ill-preparedness of Bulgarian institutions, which were practically drained of motivation and expertise during a decade-and-a-half of GERB rule. Making them work in unison is extremely difficult - despite the efforts of the National Crisis Committee created by the Council of Ministers, not all state departments want to cooperate and provide their bases for refugees, and municipal authorities are far from proactive.

Refugees vs tourists

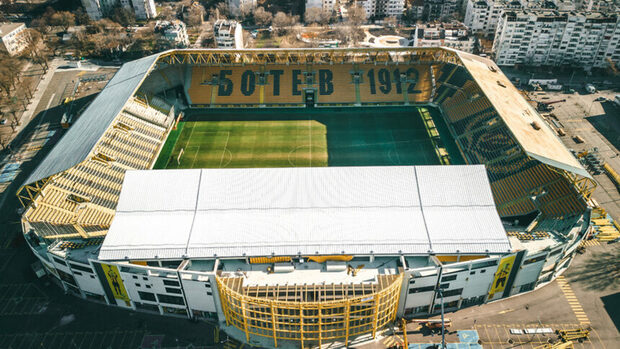

The latest data from the Refugee Agency as of Wednesday, 25 May, show that just over 59,000 Ukrainians (out of a total of 97,000 currently in the country) are accommodated in hotels - mainly in the districts of Burgas, Varna and Dobrich. The National Crisis Committee has conducted surveys to probe their mood. In short, "most prefer to stay where they are now, but when there is no such possibility, there is an understanding that they have to be relocated," says Mariana Tosheva, chairwoman of the State Agency for Refugees (SAR).

A week before the deadline set by the state and the hotels, the relocation options were still not completely clear.

The administration's initial plan was to provide alternative accommodation for the Ukrainian refugees mainly in departmental holiday complexes. It quickly became clear, however, that these places would not cover people's needs - at best they could provide about 35,000 beds, and there is little information about their present condition.

It was decided only a week ago that the state-sponsored program for accommodation in hotels and guesthouses would continue over the summer, but with a budget reduced to 15 BGN per day per refugee with three meals included, from the previous 40 BGN. "On the one hand, the state is obliged to shelter people under the [EU refugee] directive, but on the other hand, integration is key. Some of the state-owned accommodations are in isolated places and it would be difficult for the refugees to fit in and start working there," says Krasimira Velichkova, who is an adviser to Deputy Prime Minister Kalina Konstantinova and is part of the refugee crisis staff. According to Olena Shopova of the Mati Ukraine association, also a member of the Crisis Committee, this scheme helps holidaymakers who used to rely on Russian and Ukrainian tourists, who were coming in the hundreds of thousands before the war and Covid.

Hoteliers' attitudes to the new program vary, depending on the location of their hotels and whether or not they have been booked since the beginning of the summer. Some hotels in major resorts, especially those of higher category and with long-standing relationships with tour operators, are urging the state to move Ukrainians off their sites quickly in the hope of filling them with tourists. However, the situation vis-a-vis charter flights is uncertain. Some hotels are waiting for imminent tourist arrivals and are nervous about the sluggish actions of the state.

According to data from the Crisis Committee, as of 25 May, there is marked interest in the new program - a total of 359 hotels and guesthouses with a capacity of more than 25,000 beds have said they want to continue accommodating refugees. Enrolment continued until 27 May and the end number is likely to increase further. These include smaller sites in seaside municipalities as well as places in other cities around the country. Although 15 BGN per day may not sound like much, the income from a room for two per week is 210 BGN - more than lower-end sites would get if they relied on weekend occupancy only, as is often the case in towns and smaller resorts. Through this program, the needs of about half of the refugees will be covered.

And the rest go to villages, cities and wherever there is space

The other Ukrainian refugees are due to be relocated to state-owned holiday homes around the country. Such accommodation can provide up to 35,000 beds, and according to the Crisis Committee, they are mainly, but not exclusively, located around the coast. The Committee did not provide a precise list of sites, but cited holiday bases owned by the Internal, Education and Defense Ministries, as well as Municipalities, in Sunny Beach, Sozopol, Pazardjik, Nesebar, Razgrad etc.

Still, some of this accommodation needs repairs, which cannot happen quickly, and the Committee keeps asking the various ministries for references. Alas, not all ministries and state companies have shown willingness to make their stations available to refugees instead of employees, even though the Council of Ministers has obliged them by a decree.

The transport of the Ukrainians, on the other hand, will be orchestrated with the assistance of the regional administrations of the respective regions, which must organize the transport by buses or trains.

Who foots the bill?

The new programme will require a substantial budget. The amount of 15 BGN for a refugee per day applies to both private and public sites. With a total of 60,000 people that have to be covered, the bill would be about 1 mln BGN per day, or about 27 million BGN per month.

The funds for the refugees are coming from two separate streams. One source is funds from unfulfilled EU projects, which can be redirected to help refugees. This is expected to bring in close to 90 million euro, which, under the new Care instrument, will be packaged into new projects for which procedures will be launched under the Public Procurement Act.

Another potential source are the funds already received from the EU for anti-crisis measures under the React EU programme - a total of 148 million euro. Of these, 100 million euro have already been spent on targeted business support and the balance of 48 million euro will be directed to the refugees' needs, Krasimira Velichkova explains.

Additional funds will also be made available to EU Member States under the Asylum, Migration and Integration Fund by extending the implementation period of the 2014-2020 programmes by one year and providing access to unspent amounts. The Fund for European Aid for the Most Deprived (FEAD) can also support measures to provide food and basic material assistance such as clothing and hygiene products.

Will they stay or will they go?

Ukrainians are fleeing a war that directly threatens their lives - they are not economic refugees - and they clearly want to return home as soon as the war ends. Some of them are already doing so - according to the Crisis Committee, there is already a marked outflow of refugees leaving Bulgaria for Ukraine - while a few weeks ago, there were about 2,000 people arriving every day, they have now decreased to 200-300 a day. On the other hand, no matter how the war in Ukraine develops, it will take time to rebuild the country. Some Ukrainians will probably prefer to stay in the EU, even if they can go back to their homeland.

A wave of refugees is a test for each EU member state, and, in fact, most of them have a relatively limited experience of accepting migrants. Bulgaria's erratic actions are therefore not unprecedented. However, the country can and should use the summer months to look for solutions to properly accommodate those remaining here, in order to integrate them in the employment market and in society as a whole. It is important, however, that the abundance of civic energy expressed at the beginning of the refugee wave prevails and is built upon with the mobilization of the state. Without this, the chance to help those in need will be completely wasted.

Bulgaria misses its chance to keep Ukrainian workers

Ever since the beginning of the war in Ukraine the Bulgarian government saw the coming refugee wave as not only an opportunity to help people in need, but also as a solution to severe problems afflicting its labor market. Bulgarian businesses then told the cabinet that they could employ at least 150,000 people. However, these intentions have collided with reality since then.Out of around 6.6 million Ukrainians fleeing the war, around 100,000 have ended up in Bulgaria, with about half of them of working age.They are educated (70 percent have university degrees), and want to work (70 percent say they are ready to start immediately). But this potential still remains largely untapped. The main role here is played by the National Crisis Committee led by Deputy Prime Minister Kalina Konstantinova, and from the information provided to KInsights it is clear that they are trying to organize the processes more efficiently. The state, however, is more reactionary than proactive in this case, and its actions seem chaotic and without the necessary decisiveness needed to get people employed quickly.

Making this happen is, of course, not easy: on the one hand there is the language barrier, on the other - a very large proportion of the refugees residing here are mothers of young children, for whom it is more realistic to work part-time, and this is only possible if day-care centers are set up. It is also important what economic zones the refugees are placed in. Most of them are on the Black Sea coast and some of those who remain there will have the opportunity to work in the tourist industry as the holiday season begins. It will be very different for those who are relocated to government holiday homes in remote resorts or in towns in the countryside.

Last but not least, the equalization of diplomas in specialized professions, such as doctors, for example, is a long and complex process for which there is no quick solution yet. Moreover, direct job opportunities are not the only thing to think about - each person also needs a number of other social services and facilities, which Western countries are much better at providing.

The picture at the moment is not too optimistic. According to the National Revenue Agency, there were fewer than 5,000 Ukrainian refugees employed on a labor contract at the end of April, or about 8 percent of those of working age. The total number is probably higher, as many are likely to be on civil contracts. The conditions of employment for Ukrainian citizens are not very rigid - the temporary protection status they receive in the first EU country where their application is lodged provides direct access to the labor market for a period of 1-2 years. They receive a registration card for the duration of the protection and a foreigner identity number.

Apart from easing access to the job market, the state will incentivize employers to hire Ukrainians. A new program was launched at the end of April, under which the state will provide employers hiring Ukrainian citizens with the minimum wage for each employee and insurance for three months. According to Social Policy Minister Georgi Gyokov, the money will come under the Human Resources Development program and can cover more than 5,200 Ukrainians. Employers will also be paid 400 BGN each for the same period to at least partially cover the cost of their new employees renting a home.

Veselin Nanov and Kalina Goranova contributed to the writing of this article.

Over the past three months, Bulgaria opened its doors to more than 100,000 refugees from Ukraine - an unprecedented inflow for the country, at least in the last century. Those fleeing the war have encountered invaluable support from tens of thousands of volunteering Bulgarians who have offered them food, care and a shelter. Yet others have also faced hostility that included (in two cases) sticking a pickaxe in the bonnet of their cars. The state and business, on the other hand, took a pragmatic approach - hoteliers hosted 60,000 people in the (formerly) empty Black Sea holiday sites while the state picked up the tab.

On the cusp of the summer season, however, the situation is very different. War is war, but tourism is money, say hoteliers, who want to exploit their properties' potential to the hilt after a series of difficult summers. Now the ball has been passed back to the state, which must find new shelter for tens of thousands of people, organize their relocation, and support and encourage their integration into the labor market. The scale of the task at hand is enormous and time is running out - the current accommodation program expires on 31 May and some seaside hotels that are already taking tourists are getting increasingly nervous.