Bulgaria remains last among all EU members in terms of Covid-19 vaccinations. And the problem is not the lack of jabs. Bulgarians just do not want to get immunised, despite having very clear evidence that Covid is not "just a flu" - the death rate in the poorest Bulgarian region, the Northwestern, was almost twice as high as the worst-hit Western region, Lombardia in Italy in 2020. Why do Bulgarians refuse the shot? Journalist Petar Georgiev delves into the topics of the specifics of national psyche, mistrust of authority and the dangerous media attitudes that galvanized anti-vax attitudes in the country.

This piece is part of the efforts of Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF) and the Association of European Journalists - Bulgaria, who try explain how Bulgarians became so mistrustful of the vaccines, and other phenomena related to the mass desinformation war that won over their hearts and minds during the pandemic. This produced a series of in-depth inquiries, which were collected under the title "Infodemics' Chronicles," part of the global #FreedomFightsFake campaign of FNF. Kapital Insight is running several of the stories that are most relevant to Bulgaria.

This is the second one we publish. If you missed the first one, check it out.

One-third of Bulgarians are afraid of black cats, broken mirrors, and Friday the 13th, according to a 2018 survey by the Sofia-based polling agency Trend. The survey revealed some expected concerns among respondents in the country, but their main fear has nothing to do with folktales and superstitions. 66 percent of Bulgarians believe that a far greater danger is lurking in the shape of man-made diseases created with the aim of selling drugs.

Two years later, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, many don't hide their suspicions that something about the global panic over coronavirus feels wrong. Back in March, another survey explored the Bulgarians' affinity for conspiracy theories; it showed that 58 percent of respondents believe that a foreign power or other forces had been deliberately spreading the virus, while 72 percent consider the threat of the pandemic overblown - and it gained international popularity.

Bulgaria is by no means the only country where there has been a deeply-rooted scepticism about the true origin of COVID-19. However, the experts we spoke to say that Bulgarians are not a good example of conspiracies impacting modern everyday life. According to them, the widespread belief in some hidden truth can be attributed to specific socio-cultural features and historical events that have left a lasting mark on the relationship between citizens and their leaders. As the global health crisis deepens, this lack of trust in institutions could become yet another obstacle on the path to containing the pandemic.

Virus. What virus?

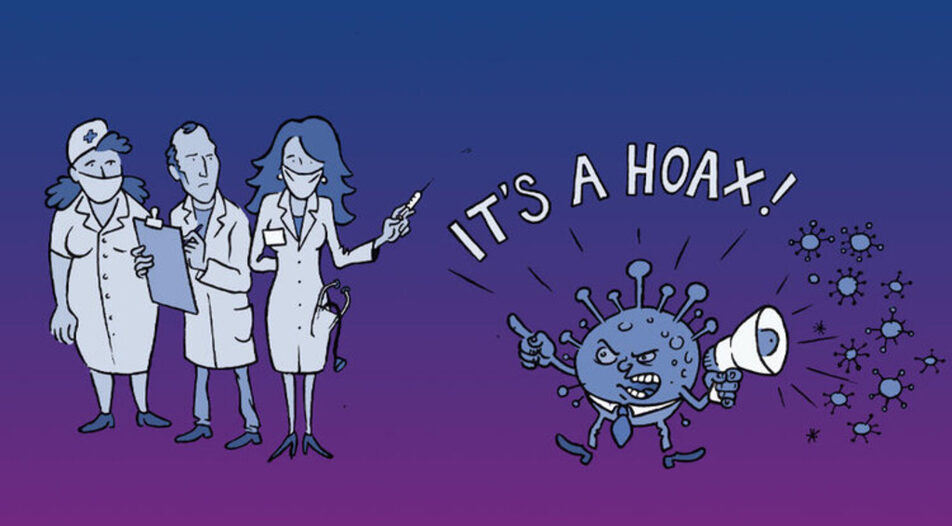

COVID-19-related conspiracies don't easily lend themselves to group analysis. Among the variety of rumours since the start of the pandemic, some of the most well-known theories are even mutually exclusive. Judging by the data from recent polls, two main suspicions have emerged in Bulgarian society. One is that coronavirus was artificially created. According to the second, the disease doesn't exist at all and the pandemic is actually a huge hoax.

At the beginning of the health crisis in Bulgaria, the government introduced strict measures against the spread of COVID-19. At the time, the belief that the virus was a scam could be partly explained by the low number of infections and deaths. In the entire month after the first official positive case in the country, between March 8 and April 8, a total of 581 patients and 23 deaths were registered. In the first week of June, however, when Trend re-examined Bulgarians' attitudes toward disinformation, the number of victims reached 160, almost seven times more than the first month. However, 23 percent of Bulgarians still said that coronavirus did not exist.

Meanwhile, in other social circles, a different opinion has been gaining ground. According to it, the infection is real but has been produced or is being spread on purpose. Every second Bulgarian supports this claim, according to a Gallup International poll conducted in March. A similar trend was reported by the Trend survey in June; 43 percent of respondents said that the disease was artificially created.

Parvan Simeonov, executive director of Gallup International's Bulgarian office, acknowledged the subjectivity of such studies. Still, in his view, the belief that coronavirus has been invented by a more developed country is a sign of public naivety.

"It makes the world cosier and easier to understand. It is always easier to think that there is a clear reason and you know it, that you can blame someone else and the responsibility is not on you," the sociologist said. "Sometimes, however, there are no easy solutions. Sometimes there is no one to slap on the wrist."

Gallup International is likely to repeat the study in the fall. According to Simeonov, most Bulgarians will remain convinced that coronavirus has an artificial origin. He says that the nation's appetite for conspiracies could be explained through deeper social phenomena.

"It turned out that we firmly believe that there is something wrong about the whole thing. But this is not a sign of an underdeveloped society. It may be a consequence of socio-cultural characteristics, historical strata, local beliefs, and the current political situation."

The truth is out there

According to sociologists, the belief in COVID-19 conspiracies is not without precedent. The pandemic serves as just another reason for Bulgarians to search for some hidden explanation.

"In Bulgaria, we have a slightly more sceptical worldview," Simeonov said. "We have suffered more blows throughout history. We always expect that someone would want to hurt us. In this region, we have developed a strong Balkan scepticism that makes us doubt everything."

The political rhetoric also contributes to the spread of such conjecture. In the early stages of the pandemic, Bulgarian Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said that we would never know which "scumbag" released the virus, hinting that the virus may have been artificially created. Polls show that many Bulgarians tend to agree with Borissov. This fact is somewhat paradoxical. On the one hand, voters strongly doubt the competence and honesty of those in power. On the other, however, they share similar views regarding the origins of coronavirus, probably looking for a specific culprit for this unprecedented health and economic crisis.

Living in "the most corrupt country in the European Union", some Bulgarians feel insignificant in the context of world politics, Simeonov said. If people are convinced that the government is working against them, and at the same time doubt the ethics of the media, their suspicions cause a general erosion of trust in traditional information channels. This can have disastrous consequences for public health.

"Once you are convinced that there is a conspiracy, you stop believing in official information," Simeonov said. "And the less you trust official information, the more you look for alternative sources. And so, in search of the truth, society stumbles upon bigger lies."

For Simeonov, it seems less likely that conspiracy theories about the pandemic would infiltrate established Western democracies. This feeling is partly confirmed by Gallup's international study. The results illustrate that, unlike Bulgaria, in countries such as the United States, Italy, Germany, and the United Kingdom, most people see no reason to doubt the authenticity of the pandemic.

Still, in Washington, US President Donald Trump has made a number of populist statements not dissimilar to those of the Bulgarian prime minister. Trump first underestimated the threat of COVID-19, saying the coronavirus "will disappear", and then repeatedly blamed China for the global health crisis.

Vaccine for the mind

When a year and a half ago a programme called The New Knowledge first appeared on the Bulgarian National Television, BNT, the public broadcaster's decision to give a voice to a "show about mysticism", science and conspiracy theories stunned many of its viewers. Media experts criticised BNT for allowing host and producer Stoycho Kerev to spread misleading hypotheses regarding various issues.

However, BNT did not cancel the show, which is still being broadcast and featured on its website. Meanwhile, Kerev's work has been attracting great interest on the Internet. At the beginning of August, his YouTube channel (with over 134,000 subscribers) was among the top 100 YouTube channels with the most subscribers in Bulgaria. The size of his following is another sign of the local audience's appetite for conspiracies. Unsurprisingly, The New Knowledge also contributed to the speculations about the origin of coronavirus.

In February, when the pandemic hadn't yet hit Europe, Kerev published an episode about the outbreak in China. Krassimir Petrov, a professor of economics and finance, was invited to comment on the health risks. During the show, despite not underestimating the danger of COVID-19, Petrov made a series of dubious and unproven claims about the disease's background. One was that the virus was created in a laboratory in Winnipeg, Canada, from where it was later exported to Asia by Chinese employees. According to the Canadian public media CBC News, this rumour is categorically wrong.

Petrov also said that the pandemic had been predicted in a 1980s novel about a virus developed in a Wuhan-based lab. This theory was also disproven by Snopes. However, during the interview, Kerev never confronted his guest about these misleading statements. So far, the episode has generated over half a million views.

The New Knowledge is just one of the popular sources of misinformation about the nature and background of the global pandemic. Another example is the video titled Plandemic, in which discredited American researcher Judy Mikovits claims that a secret elite society plans to use the virus along with a potential vaccine to gain money and power. The English version of the video generated tens of millions of views before being taken down by social networks such as Facebook, YouTube, Vimeo, and Twitter. But parts of Mikovits' interview, translated into other languages, continue to live on some of these platforms, sparking new controversies. On one of the Bulgarian Facebook pages, an excerpt from the video is still available, having been viewed over 760,000 times.

Despite the efforts of health and media organizations to dispel conspiracy theories about COVID-19, interest in The New Knowledge and Mikovits' interview demonstrate that Bulgarians are regularly deceived by misinformation in the virtual world. Most users in the country are not able to spot and protect themselves from such manipulative content.

"Technology has evolved too quickly to be well understood by much of the population," said Georgi Apostolov, coordinator of the Safe Internet Center, a non-government organization which aims to raise awareness about children's safety online. According to him, the era when people learned about the world from traditional media that adhere to journalistic standards is over. "Back then, we could trust the news. We knew that someone had verified this information for us," Apostolov said. "Many people now get their information from social media and online sources that don't do fact-checking."

According to Apostolov, another reason for Bulgarians to fall for conspiracy theories more than the average consumer is the lack of information hygiene, as well as the unsatisfactory quality of education in Bulgaria. Since its establishment in 2005, Safe Internet has been teaching children, parents, and teachers how to develop critical thinking. But Apostolov points out that his team's efforts are "a drop in the ocean". According to him, the country needs a long-term strategy developed in cooperation with state institutions.

During the last school year, the education ministry for the first time introduced special classes in which students are trained to evaluate and analyse media content. The Center's experts are sceptical of this approach. "These skills must be constantly developed in accordance with the children's age," Apostolov said. "Only then, we can hope that more young people would be better at navigating the virtual world and won't be falling victim to the creators of fake news."

Along with children, misleading articles can also be a stumbling block for many adults, who in their hectic daily lives rarely consider checking a news story's author or source. "On their own and by trial and error, young people have learned that you shouldn't believe everything on the Internet," Apostolov said. "For me, parents are the most vulnerable group. When parents themselves don't have critical thinking, they take information for granted and spread conspiracy theories, this also affects their children."

As children and the working population gradually learn about the dark side of the Internet, misinformation remains detrimental to the elderly. A recent US study found that people over the age of 65 are almost seven times more likely to share fake news on Facebook than young readers. The same age group continues to be the most endangered by coronavirus, according to an analysis by the Kaiser Family Foundation.

Sensational stories about unproven COVID-19 treatments have been circulating regularly since the beginning of the pandemic. Some of the advertised medications not only don't eliminate the virus, but also harm the body. In an effort to protect themselves from the disease, proponents of conspiracy theories and controversial therapies may unknowingly worsen their health. This risk only underscores the importance of carefully picking out trustworthy news sources.

Peter Georgiev is a freelance journalist covering sports, technology and international politics. With his documentary podcast Victoria, Georgiev explores social issues and the relationships between diverse communities through the lens of football. He previously worked for Bulgarian National Television where he hosted a weekly program about the European Union.

Bulgaria remains last among all EU members in terms of Covid-19 vaccinations. And the problem is not the lack of jabs. Bulgarians just do not want to get immunised, despite having very clear evidence that Covid is not "just a flu" - the death rate in the poorest Bulgarian region, the Northwestern, was almost twice as high as the worst-hit Western region, Lombardia in Italy in 2020. Why do Bulgarians refuse the shot? Journalist Petar Georgiev delves into the topics of the specifics of national psyche, mistrust of authority and the dangerous media attitudes that galvanized anti-vax attitudes in the country.

This piece is part of the efforts of Friedrich Naumann Foundation for Freedom (FNF) and the Association of European Journalists - Bulgaria, who try explain how Bulgarians became so mistrustful of the vaccines, and other phenomena related to the mass desinformation war that won over their hearts and minds during the pandemic. This produced a series of in-depth inquiries, which were collected under the title "Infodemics' Chronicles," part of the global #FreedomFightsFake campaign of FNF. Kapital Insight is running several of the stories that are most relevant to Bulgaria.