Journalists speaking the truth about those in power is a rare occurrence in Bulgaria's current captured media environment. And the few who dare practice it often hit a wall of silence. Ignoring questions, mocking reporters, avoiding the pressing issue, or simply shunning public media, is now the stock in trade of party leaders, ministers and senior bureaucrats, or even their purported opponents.

This trend became more blatant during the recent electoral campaign. The incumbent Prime Minister did not deign to respond to journalists' questions even once. And the leader of what was to become the second largest party in Parliament - "There is such a people" (TISP) Slavi Trifonov, circumvented the media and gave his only Q&A session to voters over Facebook Live.

These media-hostile attitudes are not limited to the highest echelons of power, although they definitely lead the way. Some ministries outright refuse to respond to media enquiries, especially by some "unfriendly" newspapers such as the sister-publication of Kapital Insights, Capital weekly. They prefer to kick the can down the road when reporters send them requests under the Freedom of Information Law (FOI), and even when they lose court cases they sometimes still fail to provide the information required.

This is a serious problem not only for the politicians and the media, but for the general public as a whole. In an ideal situation, governing a country is a joint venture between those in power and its citizens. They can only work together if they communicate. In a less-than-ideal situation, those in power have to at least respond to media questions for the sake of public accountability. But this basic principle of democratic governance has been applied less and less in recent times.

The sound of silence

The trend is far from new. Its roots are likely embedded in the totalitarian reflexes of many older politicians, born and bred in a system where the government had no obligation to respond to the media or to its people. In modern times, the premiership of Simeon Saxe-Coburg Gotha set the standard for ministers to be "masters of silence and not slaves to words," philosopher Stefan Popov recalls.

What was a problematic development in the lively and pluralistic media environment of the early 2000s became the norm as media became monopolized and less free in the 2010s. High-ranking politicians only went to tightly monitored interviews, where they felt more like the hosts than the ones under scrutiny. Questions were set in advance and no follow-ups were allowed. Instead of bringing representatives from opposing sides to debate, TV hosts introduced the absurd innovation of bringing them in one at a time, with the "debate" happening in absentia. This left the illusion of pluralism, but turned political discussions hollow.

Why did TV channels consent to that? Because otherwise they wouldn't get politicians on their programs, while their competitors would gladly accept the terms of the sending party. The most notorious case concerns the largest private TV channel, bTV, which became a no-go zone for members of the Oresharski cabinet (2013-2014). In more extreme cases, journalists who probed too much could lose their jobs. Such was the case with Anna Tsolova, Genka Shekerova and Miroluba Benatova, who got sidelined and later dismissed from Nova TV as the owners of the media felt their persistent critique of the government was harming the channel's interests.

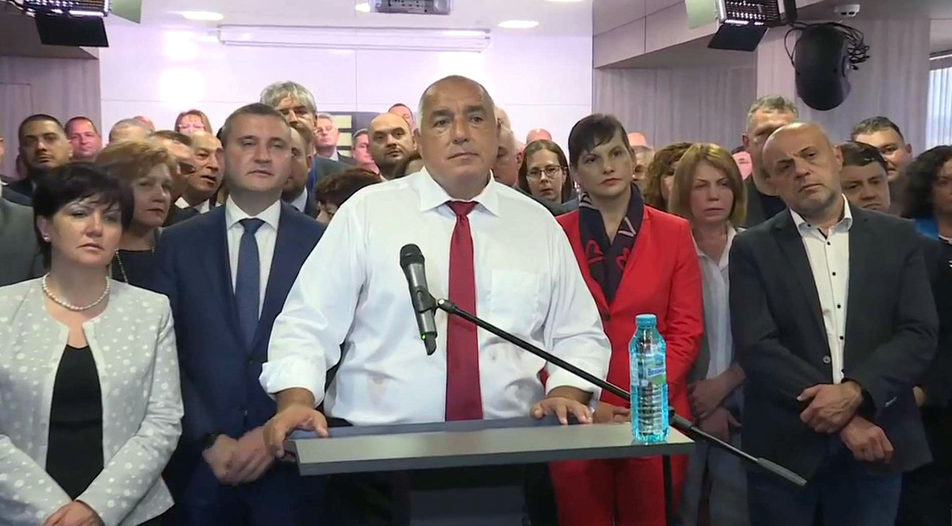

And why do politicians not want to talk to the media? Stefan Popov says it's born out of a reluctance to face the music. "Everyone putting forward arguments risks getting questioned about them," he says. And the top political brass simply can't handle such a prospect. Prime Minister Boyko Borissov last spoke to the media at a farcical press conference last June where he attempted to downplay the images of leaked photos showing him sleeping naked next to a gun and a drawer full of Euro notes. Reporters kept asking him questions he could not respond to without embarrassing himself - or implicating himself in a crime. So in the end he just blabbered without ever seeking to address the subject in a meaningful way. Since then, with a couple of exceptions, he has only spoken over Facebook Live videos, with no journalists around.

A civilizational problem

Lawyer and FOI expert Alexander Kashamov believes that the erosion of debate in Bulgaria is indicative of a civilizational problem, a tarnished legacy from the unfinished transition away from totalitarianism. "The National Assembly itself turned into a symbol of this culture. Its role is to discuss issues of public interest, but this is not happening. Laws are introduced without any public discussion, or they are changed at the last minute in Committee meetings without anyone uttering a word about it," he laments. Significantly - even notoriously - Mr Borissov has not attended a single Parliamentarian questioning by the opposition for over a year, despite being formally obliged to do so.

What starts at Parliament level spreads down to the lowest ranks of the administration. Many ministries simply refuse to respond to journalist questions, especially those from critical media outlets. For example, the Environmental Ministry stopped responding to Capital Weekly's written questions a year ago and have not answered the phone to our reporter since the time of former minister, Neno Dimov, who got dismissed in early 2020.

The ministry also refuses to obey the FOI act and has failed to respond in the two-week period to over ten requests for information from Capital's reporter. On one occasion it demonstratively sent back a requested document (National Park governing plan) in an illegible, poorly scanned format (see picture). A similar "broken printer" excuse has been used by the Internal Ministry as well.

Many more examples can be cited. Simple questions about a questionable appointment of a government-friendly journalist at a high-ranking EU post have not been answered for over two months by the Regional Development Ministry. The de facto head of the institution, deputy Minister Nickolay Nankov, has not given a single briefing for over a year, but is often a "guest" of Mr Borissov's Facebook Live videos from his eponymous jeep. The Energy Ministry is another case in point - if there were no "broadcasts" from the jeep by the Prime Minister, the developments in the Bulgarian energy sector would be shrouded in mystery, including the halting of the 10-billion euro Belene Nuclear power plant project, or the changes of parameters to the 1,5 billion euro TurkStream gas pipeline.

Feigning frankness

On top of all that, institutions like the State Prosecution imitate openness, while refusing to share details about key investigations linked to those in positions of authority. A glaring example is how Prosecutor General Ivan Geshev and his acolytes gave an hour-long presentation on the "Russian spies" a few weeks ago. No questions from journalists were allowed; of course, it's a sensitive subject but they also failed to release any information on the investigation into the recording and pictures involving Mr Borissov, as well as all the apartment scandals that rocked the government since 2019, among others.

Underpinning all this is the shared attitude of those in power that they are not obliged to respond to any outside probing. Only those who appointed them can expect an answer. This is a feudal mindset contravening basic democratic principles. Unfortunately, judging by the actions of the likely successors of GERB from TISP, this trend is unlikely to change soon.

Journalists speaking the truth about those in power is a rare occurrence in Bulgaria's current captured media environment. And the few who dare practice it often hit a wall of silence. Ignoring questions, mocking reporters, avoiding the pressing issue, or simply shunning public media, is now the stock in trade of party leaders, ministers and senior bureaucrats, or even their purported opponents.

This trend became more blatant during the recent electoral campaign. The incumbent Prime Minister did not deign to respond to journalists' questions even once. And the leader of what was to become the second largest party in Parliament - "There is such a people" (TISP) Slavi Trifonov, circumvented the media and gave his only Q&A session to voters over Facebook Live.