The Bulgarian health system is shaky but is still holding up surprisingly well compared to more developed countries

Bulgaria closed its borders to the threat of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic very early, and implemented strict social distancing measures, including closing the capital, Sofia, for entry and exit. As all this happened in early March; by the end of April the situation in the country was reassuring: fewer than 1,500 confirmed cases and fewer than 70 dead.

Thanks to the mobilization of police and other support measures, the health care system survived virtually intact and were spared the severe pressure faced by countries like the UK and Italy.

The success of the initial tough restrictions helped to reassure the government and the people that the worst was over. Then all measures for containing the spread of the infection were suddenly eased.

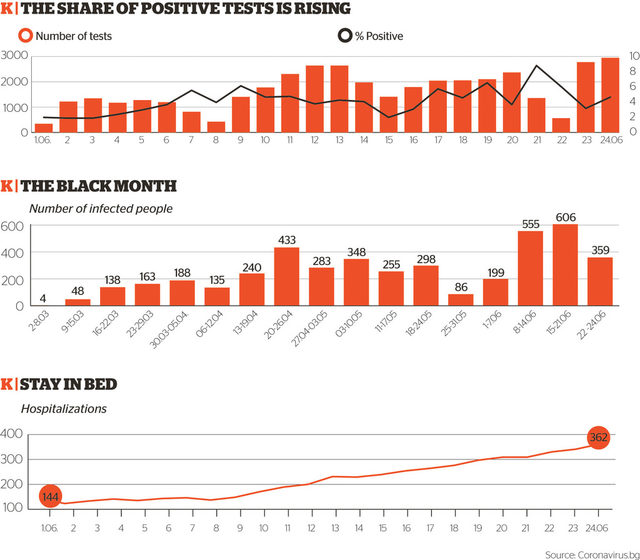

As a result, in June, Bulgaria was one of five countries in Europe where the coronavirus epidemic escalated most rapidly. As of July 1, the total number of reported cases in the country has doubled compared to June 1, which means that as many infections were registered last month as in the previous three months combined.

According to this indicator, Bulgaria ranks fifth among 36 countries in Europe. Leaders are North Macedonia, Kosovo, Albania and Moldova, and immediately after Bulgaria is Sweden, where the authorities from the very beginning have pursued a herd immunity strategy, imposing almost no restrictions.

The incidence rate during this period is similar - while on June 1 there were just over 360 cases per 1 million population, a month later there were almost 720 cases per 1 million people.

Bulgaria, Serbia, Kosovo, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Slovakia were the only countries in Europe with a steady increase in infections during the four weeks of June. On July 1, Bulgaria reported a continued rise in cases on a weekly comparison basis for the fifth week in a row.

Two factors must be considered here. First, expressed as a percentage of total tests performed, the average detected incidence is still below 6% and has been ranging from 5 to 7% throughout the pandemic. Second, the overall number of infections in the Balkans and Eastern Europe remains lower than in Western Europe despite the increase in June.

The health care system has not only survived, but it has also managed to avoid disruption to other key functions such as examining patients with other diseases and treating emergencies - something that proved to be a problem for the British system, for example. Even now, the epidemic is growing relatively slowly thanks to the almost heroic efforts of regional health inspectorates (currently the rate of spread is about 1.3, i.e. 10 coronavirus-positive people infect 13 others).

This, however, can still change in an instant. According to doctors, the tolerance threshold of the system is 300 people a day, and Bulgaria, unfortunately, has already made huge strides towards it. According to health officials, if the number of infections is not reduced in the summer months, in early autumn with the flu and other seasonal respiratory diseases, we may quickly face a health catastrophe - the number of patients will exceed the system's capacity to help them.

It is hard to implement containment measures when people don't believe you

It is easy to guess why Prime Minister Boyko Borissov, who personally takes all decisions in this crisis, is afraid to resume tougher measures.

First, because at this stage they can lead to a stronger public backlash. This is happening now in Serbia where the authorities have allowed the epidemic to develop undisturbed for weeks and even openly lied about the number of those infected before the elections in late June. Now the health crisis is out of control again and the government gave up plans to reintroduce the curfew, following resistance from thousands of protesters who stormed the parliament building. In a situation where the Bulgarian government is already faced with daily protests in the streets demanding its resignation over alleged corruption, working under siege with every action under scrutiny, the introduction of new serious bans would be met with great distrust.

A potential lockdown of cities is therefore completely ruled out. The inability of those in power to implement measures contrasts with changing public attitudes. According to a Gallup International poll conducted between June 25th and 27th, most Bulgarians still oppose a new tightening of measures, but anxiety and fears are growing. At the beginning of June, 51% feared that they or a member of their family could become infected, and at the end of the month their share was already 60%. The "fearless" - those who are not afraid of the virus - are down to 39% from 48% just a month earlier. Only 38% believe that the infection is under control - contrasted with 72% in early June. And 59% say the government is doing well in managing the epidemic, compared to 77% in the previous survey.

However, even if society were to accept them, tougher measures would further deepen the economic crisis, which is yet to show its true scale.

Economic support measures were insufficient, tardy and poorly implemented

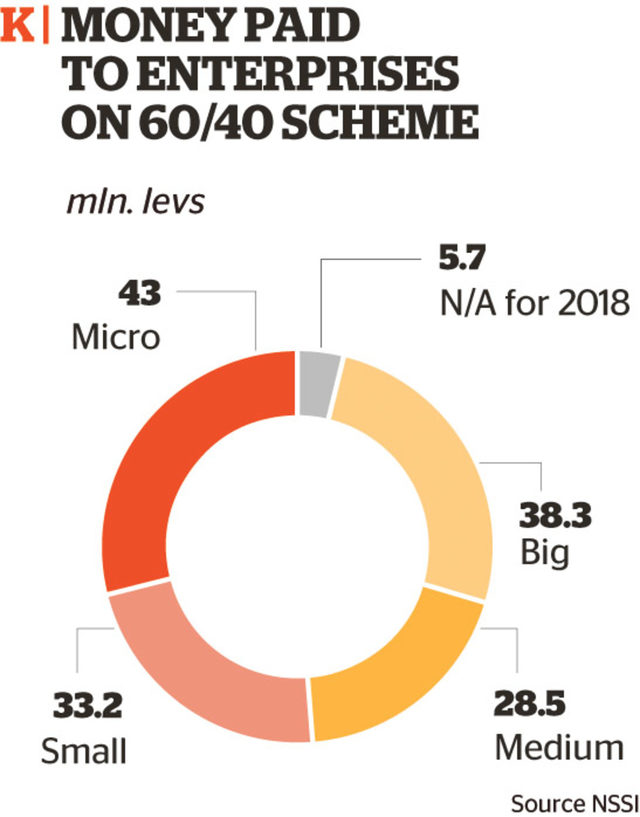

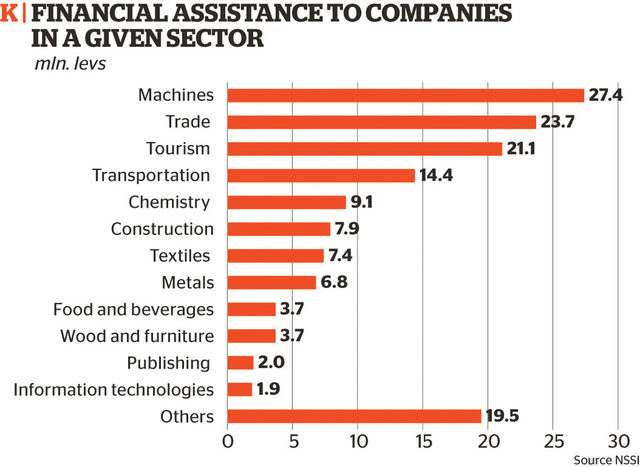

A full 3 months after the beginning of the crisis, financial aid for enterprises in Bulgaria is still slow to reach its recipients. The only scheme announced by the government that actually works is the so-called 60/40 measure, in which the state pays 60% of the employee's salary and the employer pays the remaining 40%, plus social contributions. This discouraged many companies from applying for the program, and the other measures have not started as of July. As of the end of June, according to budget estimates, about 150 million levs have been paid out.

The first payments under the EU's Operational program Innovation and Competitiveness to companies hit by the economic consequences of Covid-19 were made at the end of June. The program is moving extremely slowly and at this speed, it will be unable to distribute grants to all the businesses who applied, at least until the end of the year. The recent tightening of the rules and bureaucracy also means that many are likely to avoid this program as well.

While the government-supported programs seem inadequate for small companies, there are no programs for big businesses. A KQ survey among the largest of them has already shown that they do not consider the government's measures adequate at all, nor have they taken advantage of them.

Another option is an instrument for debt guarantee through the Fund of Funds - a public institution that oversees the financial instruments of European programs. This instrument was announced at the beginning of the crisis - in March and is not yet open to candidates. The Fund told Capital that it will be released "when the time comes". Apparently, the time hasn't come yet.

There is insufficient economic data for accurate projections

This leads us to another discovery, which is not unique to the coronavirus crisis, but is emphasized by it: the lack of adequate statistics in Bulgaria.

This can be seen both in the ways in which health statistics are kept - incomparability of data, lack of some data - and in other areas, such as local economic statistics, indicators of economic activity and others.

Even the fastest indicator, which should be the most adequate: unemployment, is measured in several different ways. Data from the government's Employment Agency and those from the statistical office NSI sometimes differ due to different approaches, and recently the number of weekly unemployed even disappeared for a while, because of misunderstandings between the two.

Without reliable data, it is very difficult to make decisions. Just as it is difficult to make decisions about a pandemic without knowing what is happening to the virus in society, it is impossible to make economic decisions without knowing the situation regarding business.

In Bulgaria, such pieces of data are either missing or hidden - the databases of the National Revenue Agency and the National Social Security Institute, for example. They are only seen when cabinet ministers cite numbers on TV without anyone else being able to independently verify and analyze them. This not only deprives citizens of the opportunity to check the government's actions, but it also deprives the government of new ideas, as no one can make meaningful proposals without adequate data.

A ray of hope in the whole story is that even now some data can be found in an open format on the websites of institutions. The coronavirus outbreak and the pick-up in digitalization it enforced will surely help speed up this process.

It may take up to 3 years to recover

Capital weekly used the expertise of McKinsey & Co for a forecast of what will happen to the Bulgarian economy.

In a special webinar, two representatives of the company - the partner from the Budapest office Andras Kadocsa and the associate consultant from Copenhagen Boris Georgiev, presented their projections.

Kadocsa outlined nine scenarios for the recovery of the global economy, depending on the effectiveness of virus containment and government measures to help businesses and households. The scenarios are based on a survey of nearly 2,500 managers contacted by McKinsey twice - in early April and a month later.

In April, the most likely scenarios among them were two, dubbed A1 (31% of respondents) and A3 (16%). In A1, the virus will return in waves, while in A3 its spread is rapidly limited. A month later, the percentage of respondents seeing A1 as the most likely scenario has doubled.

A1 predicts a contraction of the economy in the euro area by over 11% in 2020, in Germany by 10%, and in Bulgaria by 8 - 10%. The economies can be expected to return to the pre-crisis levels in more than three years - by the second half of 2023. For comparison - the horizon of A3 for such degree of recovery is 2021.

According to Andras Kadocsa, the reality will be somewhere in the middle. Some countries may fall into the pessimistic and others into an optimistic scenario. In Central and Eastern Europe, for example, this depends on three factors - the disruption of value chains, the extent to which tourism is crucial for the local economy and the reliance on remittances.

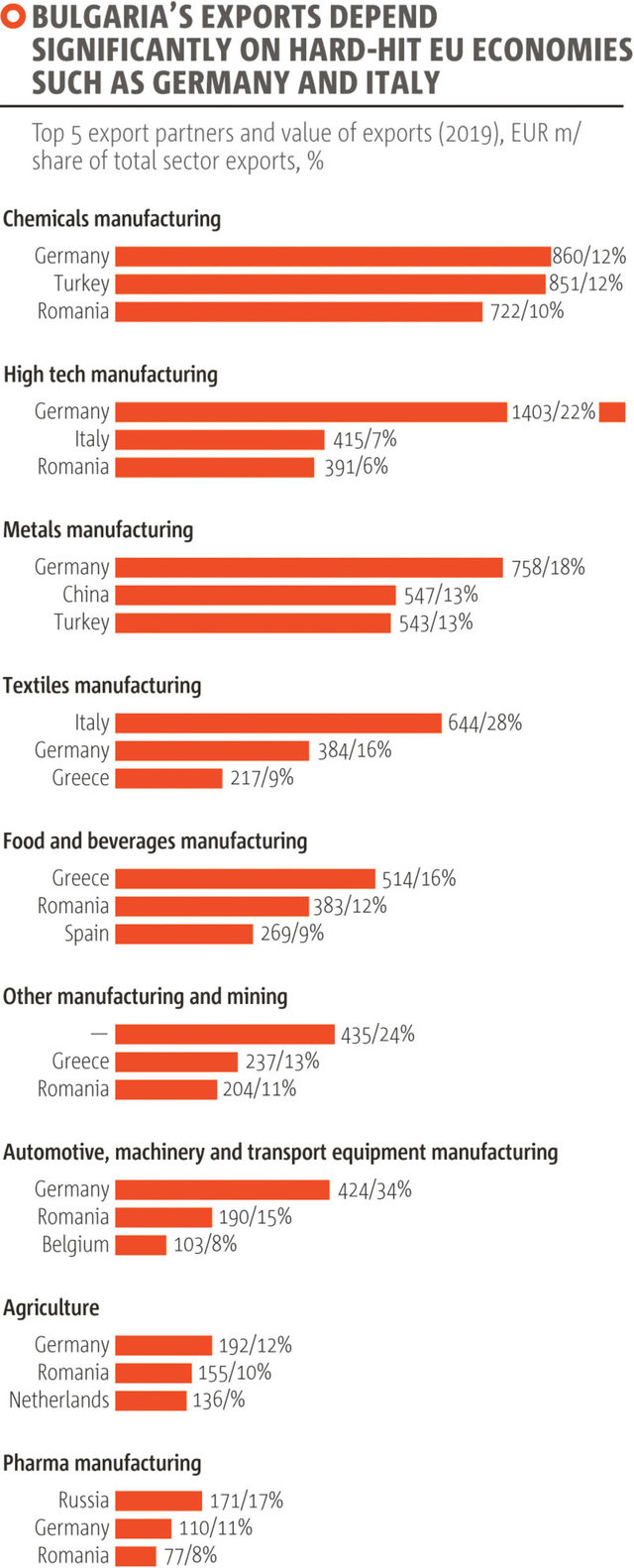

Fortunately, the Bulgarian economy is less dependent on exports and foreign demand compared to other countries such as Slovakia and Hungary. Exports, for example, account for about 93% of Slovakia's GDP and about 84% for Hungary, while in Bulgaria that percentage is 67%.

Hotels and restaurants in Bulgaria will be hit hard by the reduced flow of foreigners and the coronavirus-related restrictions, but tourism accounts for about 8% of the country's GDP, compared to 20% in Croatia. According to McKinsey analysts, demand in the sector will shrink by 25 - 35% in total during this year, but the negative impact will be limited because the share of the industry in value-added was only 3% in 2019.

The remittances are a factor because they stimulate household consumption, but in Bulgaria, their amount is not so significant, as they are equivalent to 4% of GDP compared to 11% in Ukraine, for example.

However, low incomes and productivity weigh on private demand in Bulgaria, which means that the crisis will have a significant effect on trade - the largest sector in the country with over half a million employees and value-added of 7.3 billion euro generated in 2019. According to McKinsey, demand in the sector will drop by 5-15% in 2020 compared to last year in the most likely scenario.

The export-oriented industries will be hit hard. One-fifth of Bulgaria's high-tech products sold in Germany (1.4 billion euro). The main markets for Bulgarian metal goods are Germany (758 million euro), China (547 million euro) and Turkey (543 million euro). Exports account for 67% of Bulgaria's gross domestic product and two-thirds of exports depend on the EU.

Tourism is finished (at least in its present form)

One tangible consequence of the corona crisis is the damage to the tourism sector. In March, the forecasts pointed to a drop of around 80% drop in bookings and future tourists in the summer season. The best-case scenario was a limited drop of around 50% compared to 2019, assuming Bulgaria would be among the first "open" destinations and would have agreements with other countries in the EU.

While that has been the case up to June, in the past two months the rise in corona cases has prompted other countries like the UK and Austria to put quarantine in place for people returning from Bulgaria. Many chartered flights were cancelled.

Coupled with the slow recovery in other markets and the full closure of the Russian market (because of the denial-of-entry rule) that has basically destroyed any chances the Bulgarian tourism industry had this year.

The two flickering hopes are the Romanians and the fact that Greece has all but closed its borders to Bulgarian holidaymakers which will help bring more Bulgarians to the Black Sea.

Yet this is a long way off from filling even the official 230,000 beds in the seaside resorts (not counting all the unofficial ones).

According to Grigor Fidanov, owner of the big Bulgarian hotel chain Grifid, around 30% of all tourism establishments on the country's Black Sea coast will be open this year.

Bulgaria is dependent on tourism, yet not as much as one would expect: in 2017 (the last year for which data is available for turnover and persons employed per sector) the whole Accommodation and Food sector accounted for a little over 4% of GDP and around 5% of the workforce. Taking into account the damage to all related businesses around tourism, the loss of the sector will be equivalent to around 11% of GDP but it will depend on regional differences. For example, in Burgas Region, over 60% of the workforce is connected to the tourism industry in one way or another.

This means that 2020 will be a watershed year for Bulgarian tourism. Many will fail and those who survive will possibly have to adapt to stay afloat. A recent revival in the search for smaller guest houses and mountain areas is a sign in that direction. But the going looks rather tough for the whole industry

The Bulgarian health system is shaky but is still holding up surprisingly well compared to more developed countries

Bulgaria closed its borders to the threat of the novel coronavirus (Covid-19) pandemic very early, and implemented strict social distancing measures, including closing the capital, Sofia, for entry and exit. As all this happened in early March; by the end of April the situation in the country was reassuring: fewer than 1,500 confirmed cases and fewer than 70 dead.