Bulgaria, unfortunately, has built an image of a country deeply affected by organized crime. This image is rooted in the 1990s, with its rampant extortion and racketeering by criminal 'ensuring groups' whose stickers were obtrusively visible on cafes, restaurants, cars and even residential buildings. The years of widespread extortion were followed by equally widespread smuggling of goods and the spread of black markets. For external observers, Bulgaria's EU pre-accession period (2001-2007) was dominated by news of public assassinations of criminal bosses and businessmen.

Since then, however, the crime situation in Bulgaria has changed significantly, yet many perceptions about organized crime shared by both foreigners and locals are unaltered. This current analysis re-examines five of the following myths in the light of crime statistics and expert estimates of criminal markets: 1) Bulgaria is a country of powerful and extremely violent organized crime; 2) It has one of the highest crime rates in Europe; 3) Bulgarian authorities are incapable of curbing tax fraud; 4) The proceeds of organized crime are huge and constantly growing, and 5) Organized crime exerts a high social cost but law enforcement bodies lack the capacity to tackle it.

Bulgaria is a country of powerful and extremely violent organized crime

NOT ANYMORE

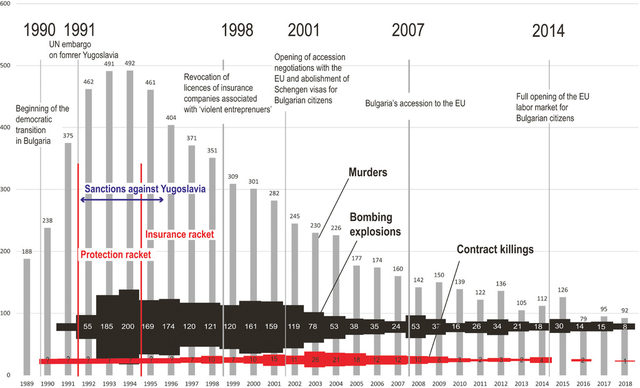

Аt the time of Bulgaria's accession to the EU, experts from the Center for the Study of Democracy, a Sofia based think-tank, who had been monitoring the state of conventional and organized crime in Bulgaria and Europe since the mid-1990s, were often asked about the impact of organized crime in the country. Was it rising or was it subsiding? Our general perception was that the trend was downward but we needed verifiable data to back this assessment. By definition, organized crime is an opaque phenomenon which is very hard to measure using standard crime statistics. We were looking for police data which could be clearly linked to the level of organized crime and at the same time was not prone to manipulation. Our choice fell on three indicators which are hard to conceal for political reasons, and which can be easily tracked over time: the number of premeditated homicides, contract killings, and explosions aimed at property destruction (used either to send a warning or take revenge on competitors).

Placing these three indicators on a chart (Figure 1) created a storyline not only of organized crime but also of the important events in the last three decades of Bulgarian political history.

Homicides, peaking in the first half of the 1990s, have steadily declined ever since. Contract killings, averaging about 13 per year for the period 1998-2009, are down to a couple per year in the 2010s. The use of explosives has also subsided, from a peak of 200 incidents in 1994 to fewer than ten in 2018.

These trends confirm that at least the violence associated with totally uncontrolled organized crime has been largely contained.

But how does Bulgaria compare to its European counterparts?

Figure 1 Trends in violent crime, 1989-2018

Source: Police statistics

Bulgaria has one of the highest crime rates in Europe

STILL HIGH, BUT NOT EXORBITANT

The perception of an extremely high crime rate is closely linked to the positioning of Bulgaria as 'the poorest and most corrupt country in the EU'. Comparing crime rates across countries is a rather complex task due to discrepancies in criminal legislation and police statistics. Comparing registered crimes, Bulgaria and Romania have almost 10 times lower crime rate per 100 000 population than Sweden and Finland - simply because the Nordic countries include in their count's administrative offences, while Bulgaria and Romania don't.

Victimization surveys, another possible method for international comparison, are also viewed with scepticism, as their output is considered soft data that does not capture the true-crime level. The most trusted indicator in comparative statistics on violent crime is the number of premeditated murders. In the mid-1990s Bulgaria had one of the highest rates in Europe, with 4.8 homicides per 100,000 inhabitants, followed only by Russia and Ukraine. In the 2010s, though, comparison of crime statistics (as reported by Eurostat) on a number of serious crimes places Bulgaria closer to the middle. In addition, rates for many types of crime have been going down steadily for the past two decades. A look at the homicide rate, for instance, places Bulgaria in a group with France, Finland and Malta, and ahead of most countries of Eastern Europe (Figure 2).

Figure 2 Homicide rate per 100,000 population - average for 2013-2018

Source: Eurostat

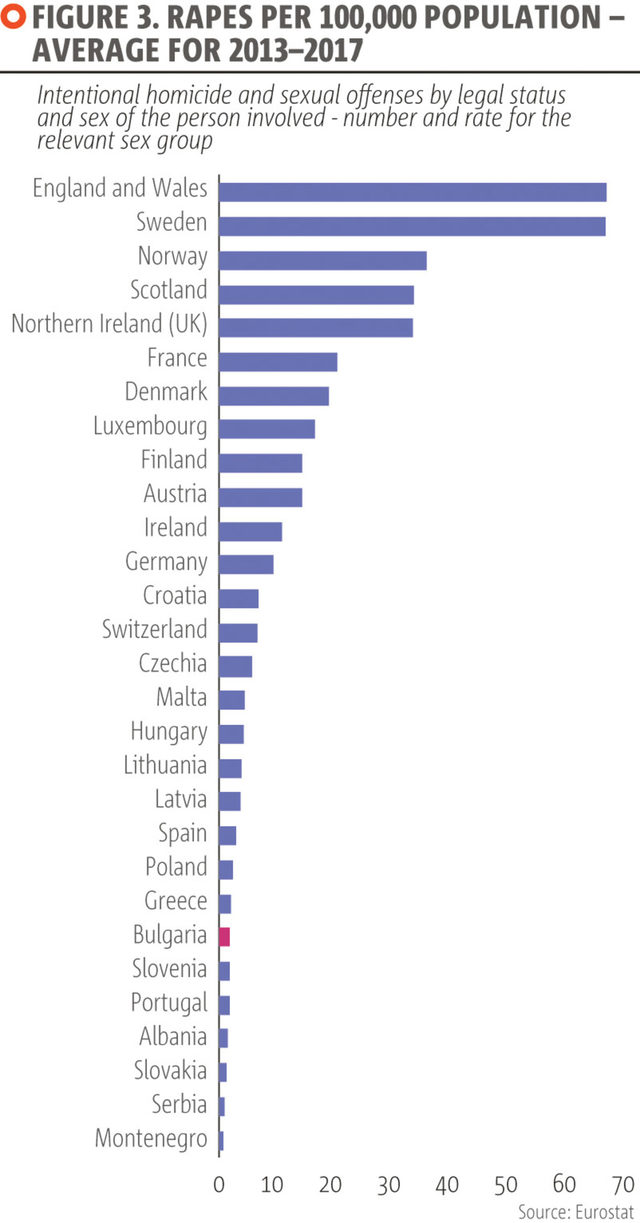

In terms of sexual crimes (rape and sexual assault), Bulgaria has one of the lowest rates in Europe (Figure 3), though there should be a cautionary note about possible differences in reporting standards.

Figure 3 Rapes per 100,000 population - average for 2013-2017

Source: Eurostat

Comparative crime statistics for the 2010s challenge also the belief that Bulgaria has one of the highest crime rates in Europe. Still, the concern that organized crime is damaging the Bulgarian business environment and robbing the state budget remains.

Bulgarian authorities are incapable of curbing tax fraud

THERE IS ACTUALLY A REMARKABLE IMPROVEMENT

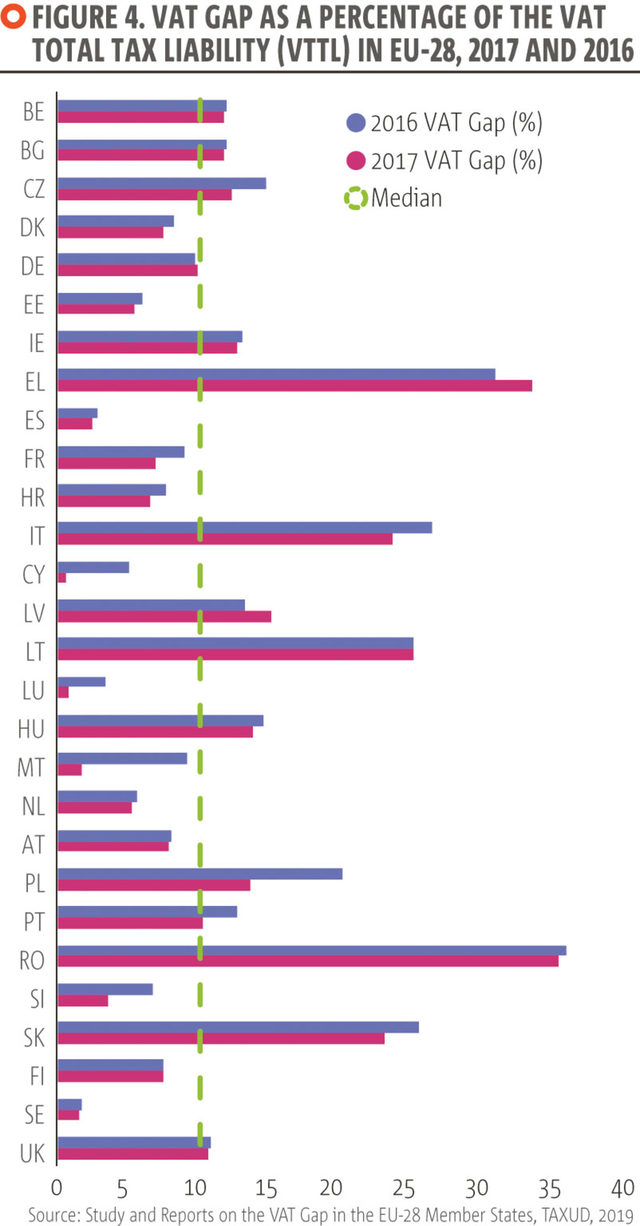

Organized crime is traditionally associated with contract murders, explosions, kidnapping and extortion. Another equally important impact is the damage caused to the competitive environment of a country. If criminal entrepreneurs don't pay taxes, it is very difficult for anyone else to compete with them. One of the best criteria for the state of a tax system of an EU member state is its VAT collection record.

The VAT Gap study commissioned by Directorate General Taxation and Customs Union of the European Commission (TAXUD) has some reassuring data for Bulgaria. The VAT Gap, which is the difference between expected VAT revenues and VAT actually collected, provides an estimate of revenue loss due to tax fraud, tax evasion and tax avoidance, but also due to bankruptcies, financial insolvencies or miscalculations. The VAT Gap for Bulgaria for 2017 is estimated at 1.22 billion levs or 11.8%, which is slightly above the EU average of 11.2% (Figure 4). Thus, Bulgaria's VAT Gap has considerably shrunk compared to the 24-25% divide of the first estimates for 2009-2011.

Figure 4 VAT Gap as a percentage of the Vat Total Tax Liability (VTTL) in EU-28, 2017 and 2016

Source: Study and Reports on the VAT Gap in the EU-28 Member States, TAXUD, 2019

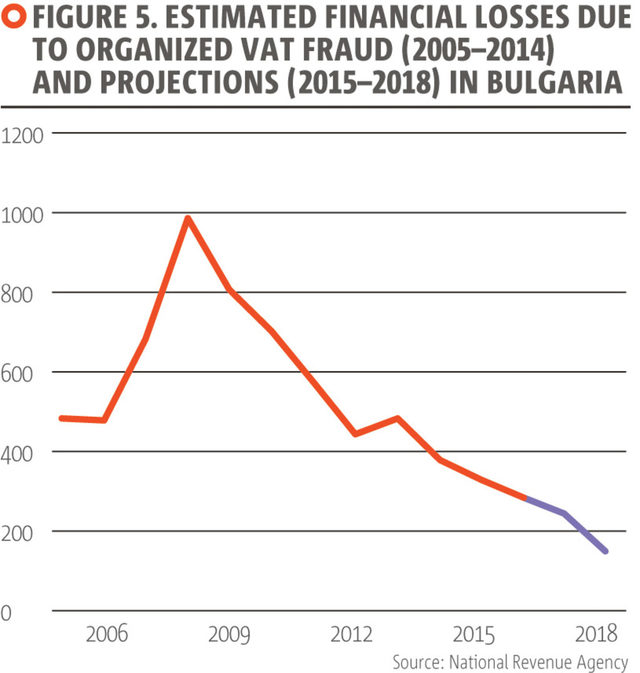

In contrast to the VAT Gap study, which uses a bottom-up approach employing macro data for the GDP, imports, exports, internal consumption, investment, etc., the Bulgarian National Revenue Agency (NRA) uses a top-down approach to assess losses from organized VAT fraud. It evaluates the revenue stated by companies which does not correspond to tax collection for the respective year. In Bulgaria, VAT fraud schemes run by organized criminal networks were extremely widespread since the turn of the century, peaking between 2007 and 2011.

Back then, even large chain stores operated by multinationals were, knowingly or not, using goods and services delivered through criminal networks. NRA estimates showed that in that period organized VAT fraud varied between 12 and 14% of the total VAT revenues. Such assessments were conducted in 2010, 2013, 2015 and 2019 (Figure 5). The significant improvement is due to the introduction of a real-time link between all cash registers and the servers of the National Revenue Agency, and the collaboration of large private companies in avoiding risky suppliers and clients.

One telling example is the fate of the largest grey marketplace on the Balkans, the Iliyantsi bazaar in Sofia, whose turnover went down by some 70% after the entry into the Bulgarian market of the Metro hypermarket retailer.

Figure 5 Estimated financial losses due to organized VAT fraud (2005-2014) and projections (2015-2018)

Source: National Revenue Agency

Proceeds of organized crime are huge and constantly growing

IN SOME AREAS THERE IS A SIGNIFICANT DROP

Measuring the total proceeds of organized crime is far from an exact science. One approach is to view organized crime as a set of "criminal markets". The levels of precision vary widely among different criminal markets. For instance, estimates for the volume of illicit cigarette trade or the number of stolen vehicles are considered sufficiently accurate, while estimates for the proceeds from human smuggling or illegal trade in fuels are usually only tentative approximations.

After the fall of communism, the sale of illicit cigarettes and car theft became the two largest and most emblematic criminal markets in Bulgaria. Their abrupt decline in the last decade is due to the collaboration of law enforcement agencies and the private sector. For instance, the reliable statistics on stolen vehicles (containing data on the vehicle's value and the circumstances of theft) was the result of the common efforts of insurance companies and law enforcement bodies. Similarly, large tobacco companies, with their regular surveys of the illicit cigarette market, and in particular the "empty pack surveys", provided a kind of dashboard showing the most problematic towns and regions of the country.

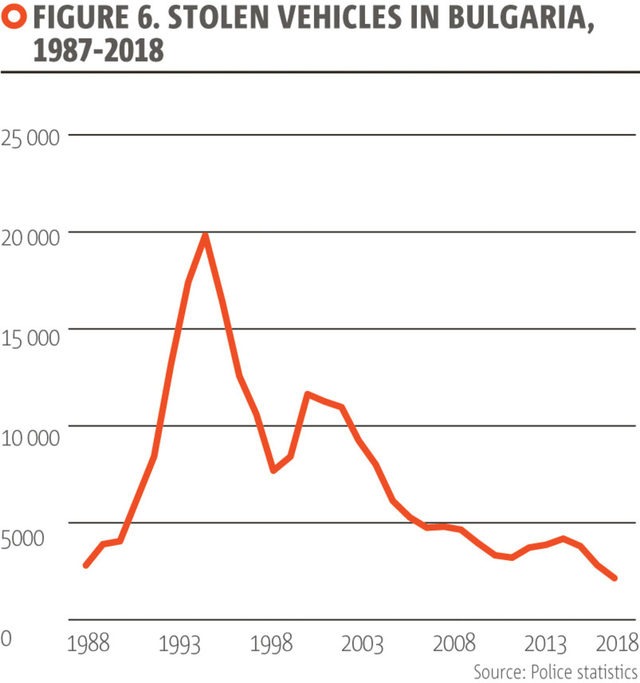

Of course, each criminal market is driven by other factors as well. For instance, the decline in vehicle theft (Figure 6) is also explained by advances in car protection technology and by the extensive import of affordable second-hand vehicles from Western Europe. Since 2000, when over 11,000 vehicles were reported stolen in Bulgaria, the number has dropped to 2,068 in 2018, or less than the number of cars stolen in the late 1980s, before the beginning of the transition to democracy.

Figure 6 Stolen vehicles, 1987-2018

Source: Police statistics

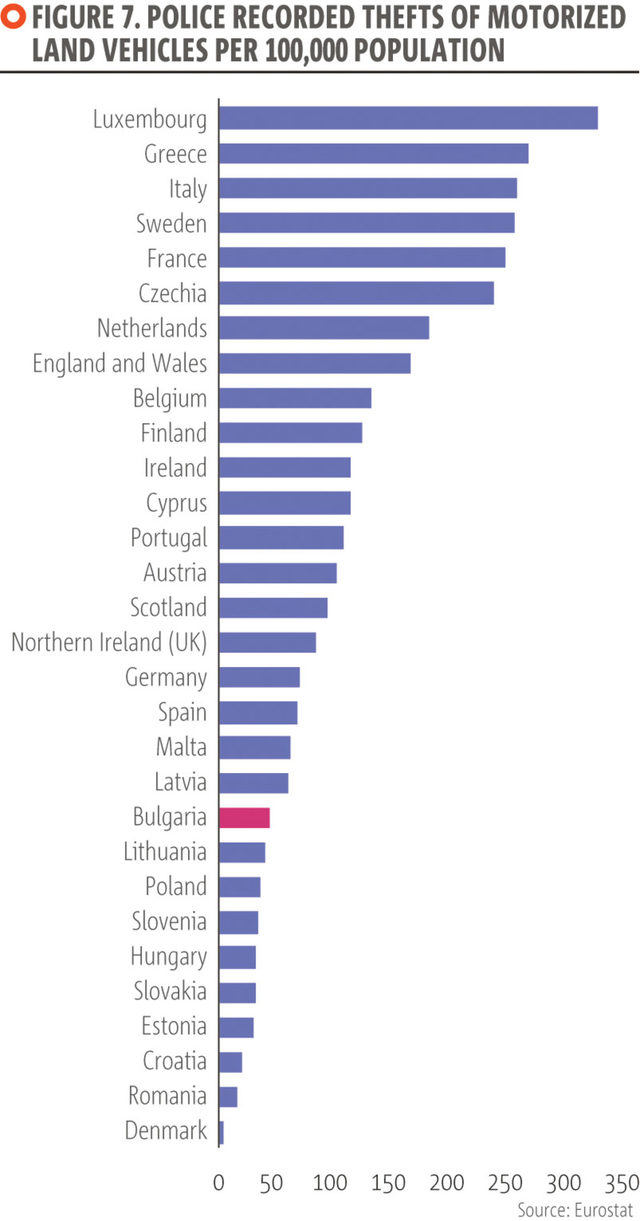

Compared to the mid-1990s, when every third car imported from Western Europe got stolen, and Bulgaria ranked among the top three European countries in terms of stolen cars per 100,000 population, the current state of the market is very different. Eurostat data for the 2015-2017 period place Bulgaria among the Member States with the fewest car thefts (Figure 7).

Figure 7 Police recorded thefts of motorized land vehicles per 100,000 population

Source: Eurostat

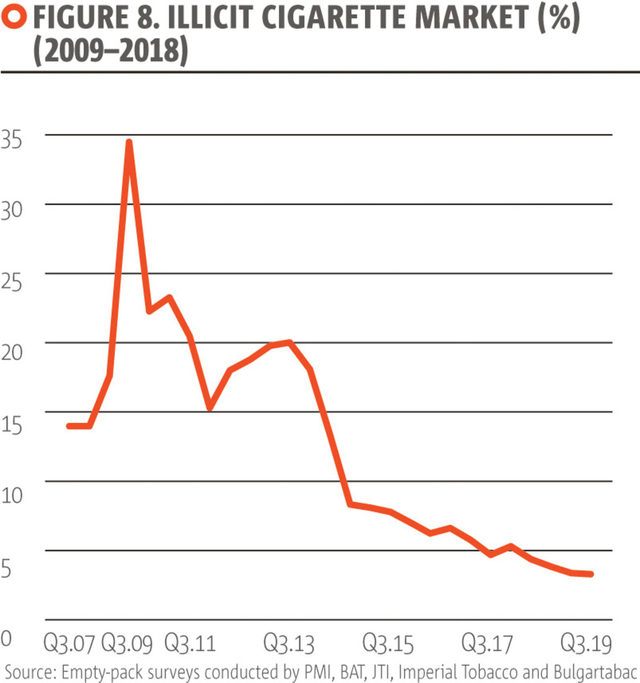

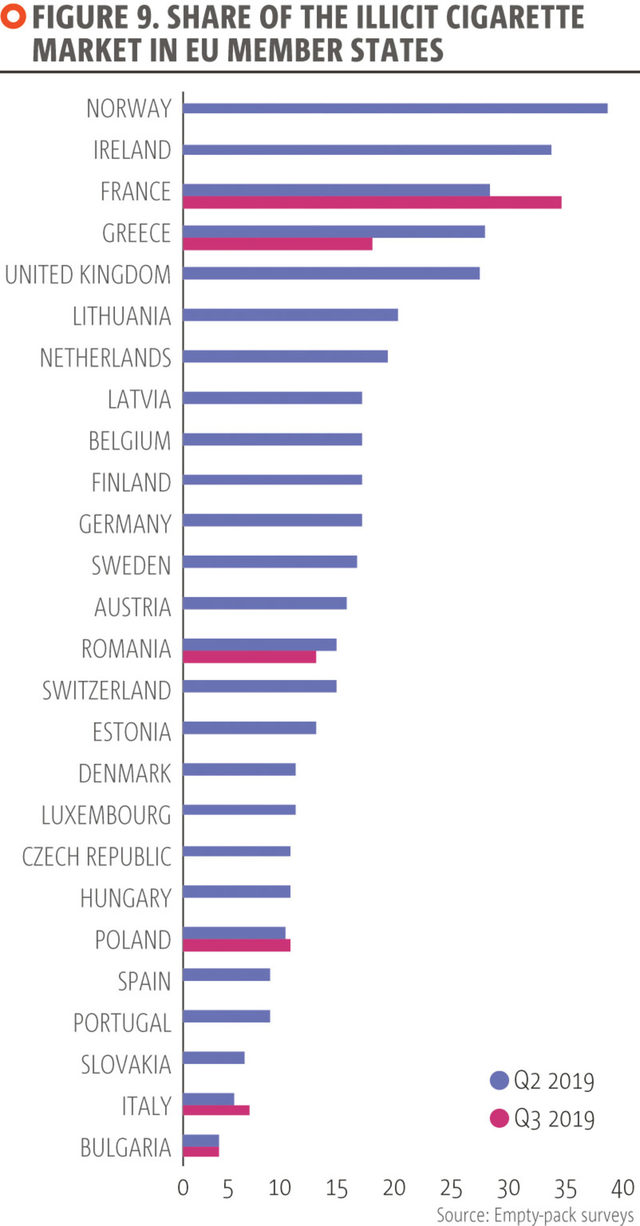

The criminal market with the most significant and, at least for the time being, the stable downward trend is the trade-in illicit cigarettes. From a country with one of the highest shares of illicit tobacco products consumption in Europe, in recent years Bulgaria ranks close to the top of European countries with minimal illegal trade. This development is even more surprising given the deep-rooted traditions in cigarette production, and the dominant role of cigarette smuggling in the business of Bulgarian organized crime groups in the 1990s. The estimated share of illicit tobacco products sold on the domestic market after Bulgaria's accession to the EU reached 35%.

After 2014, that share took a steep dive, reaching a record low of 3.3% in 2019. The proceeds of organized crime from illicit cigarettes have shrunk from over 300 million euro in 2010 to about 50 million euro in 2018. The estimated losses to the budget from unpaid excise tax and VAT have gone down from 10.6% of GDP in 2010 to 1.0% in 2018. The successful curbing of this criminal market is registered not only by the regular empty-pack surveys (carried out in Bulgaria since 2007), but also by the significant increase of excise tax and VAT revenue from cigarette sales, at a time when the percentage of smokers and the Bulgarian population itself are dwindling.

Figure 8 Illicit cigarette market (%) (2009-2018)

Source: Empty-pack surveys conducted by PMI, BAT, JTI, Imperial Tobacco and Bulgartabac

Figure 9 Share of the illicit cigarette market in EU member states

Source: Empty-pack surveys

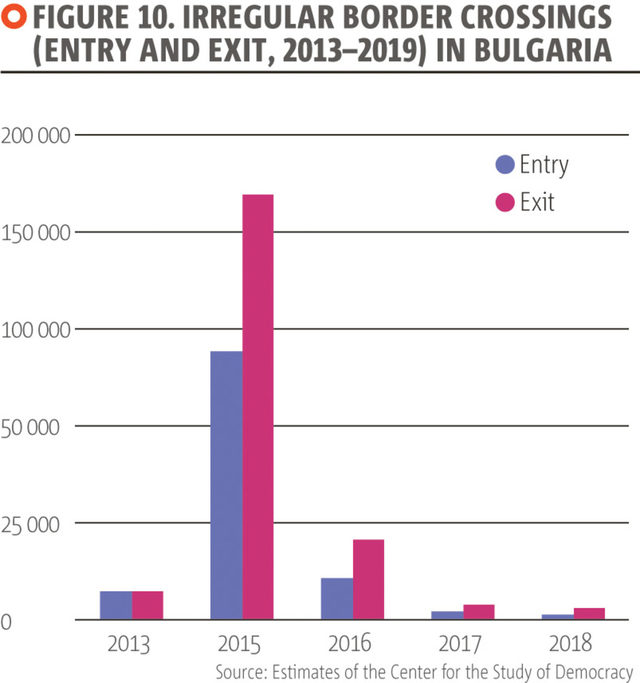

Human smuggling is a good example of how Bulgaria has managed to bring a fast-expanding criminal market under control. In 2013, when Greece introduced strict measures to curb illicit migrant trafficking across its land borders, the migrant flow through Bulgaria increased. Due to the immense migratory pressure, the migrant smuggling networks' capacity soared. Thus, during the migration crisis of 2015, they managed to smuggle through Bulgaria between 110,000 and 174,000 people with their proceeds reaching 120-130 million euro (according to estimates of the Center for the Study of Democracy).

In 2016 and 2017, the number of unlawful border crossings by migrants dropped significantly as a result of several factors such as investments in border surveillance infrastructure, the establishment of specialized units at the Ministry of Interior, mutual control between Bulgarian migration institutions and increased cooperation with Turkish authorities. Thus, the number of border crossings in 2018 went down to between 2,000 and 5,000, whereas migrant smuggling proceeds shrank to three million euro.

Figure 10 Irregular border crossings (entry and exit, 2013-2019)

Source: Estimates of the Center for the Study of Democracy

The sharp decline in three key markets of Bulgarian organized crime cannot be taken as proof that the overall proceeds of criminal groups are shrinking. Still, they are an indication that the constant growth of criminal proceeds is not absolute.

The final most pertinent question concerns what, if anything, is being done to combat organized crime in Bulgaria. For years on end, telephone fraud was perceived as a crime which police and prosecution were powerless to tackle.

Organized crime exerts high social cost but law enforcement bodies lack the capacity to tackle it

POLICE NEED COOPERATION FROM THE PRIVATE SECTOR

One of the most persistent crimes in the past decade has been telephone fraud. It is perpetrated by a relatively small group of fraudsters and in terms of cash proceeds is one of the smallest criminal markets, with an estimated total turnover of about eight million levs per year (Figure 11). At the same time, its social damage is much higher for two reasons: first, its victims are the most vulnerable citizens (predominantly elderly people living alone), and second, the bosses of telephone fraud groups are well known but remain beyond prosecution due to lack of evidence linking them directly to the committed fraud.

The crime relies on shocking and confusing the victims (for example, with claims of needing to help a terminally ill or injured relative), and by the time they contact the police (if at all), it is almost impossible to collect physical evidence. It is estimated that for every "successful" call (i.e. a call where a victim is tricked into giving away a certain sum of money or other valuables), fraudsters make thousands of unsuccessful calls. Victimization surveys suggest that one in every four Bulgarians has been the target of attempted telephone fraud in the last five years. As a criminal market, telephone fraud has demonstrated extremely high flexibility. Fraudsters exploited a network of middlemen, used pre-paid phone cards registered to third persons with no income, and moved their calling campaigns to other countries (mostly to Romania) after roaming charges in the EU were dropped.

Figure 11 Estimated proceeds from telephone fraud (2012-2018)

Source: Police statistics

It was this pattern of high volume outgoing calls that prompted the design of a technological solution that can disrupt, and in the long run destruct, the telephone fraud business model. Similar to VAT fraud, car theft and illicit cigarettes, cooperation between private companies and law enforcement agencies produced a viable solution. With the support of telephone operator Vivacom, attempts at telephone fraud were drastically reduced from over 60,000 per month at the beginning of 2019, to practically no attempts and no registered victims in the last quarter of 2019.

In addition, in 2019 twenty-six members of three criminal groups based in the towns of Gorna Oriahovica, Vetovo and Levski (the strongholds of telephone fraud) were arrested and prosecuted. It remains to be seen how sustainable this crackdown would be, but available statistics so far point to the near extinction of telephone fraud in Bulgaria. (There are indications, however, that Bulgarian telephone fraudsters have attempted to replicate their schemes in Greece).

The persisting problems with organized crime

While many of the popular beliefs about the state of crime in Bulgaria are no longer valid, the country is far from being unaffected by organized crime. The latest assessments of serious and organized crime in Bulgaria for 2018 and 2019 have demonstrated that criminal networks are successfully adapting and integrating into a number of European-wide criminal markets, exploiting the flaws in communication among Member States' law enforcement bodies.

Criminal players have also made investments in legal businesses, making it hard to distinguish between criminal and legal activity. Using a legitimate business as the cover is widespread in the illicit fuels market, VAT frauds, illicit logging and even in the export of sex services. A prominent trait of current Bulgarian organized crime is its growing connection to the white-collar crime - financiers, lawyers, high-level administrative officials and politicians.

While discarding the violent methods typically used in the past, today's criminal networks are employing administrative and political corruption to eliminate competition. Organized crime players in Bulgaria are increasingly dealing with renewable energy projects, waste processing companies, infrastructure projects, and agriculture. They are abusing EU funds and exploiting opportunities in collaboration with transnational criminal networks across Europe.

Bulgaria, unfortunately, has built an image of a country deeply affected by organized crime. This image is rooted in the 1990s, with its rampant extortion and racketeering by criminal 'ensuring groups' whose stickers were obtrusively visible on cafes, restaurants, cars and even residential buildings. The years of widespread extortion were followed by equally widespread smuggling of goods and the spread of black markets. For external observers, Bulgaria's EU pre-accession period (2001-2007) was dominated by news of public assassinations of criminal bosses and businessmen.

Since then, however, the crime situation in Bulgaria has changed significantly, yet many perceptions about organized crime shared by both foreigners and locals are unaltered. This current analysis re-examines five of the following myths in the light of crime statistics and expert estimates of criminal markets: 1) Bulgaria is a country of powerful and extremely violent organized crime; 2) It has one of the highest crime rates in Europe; 3) Bulgarian authorities are incapable of curbing tax fraud; 4) The proceeds of organized crime are huge and constantly growing, and 5) Organized crime exerts a high social cost but law enforcement bodies lack the capacity to tackle it.