The short answer to the question if Bulgaria has a consistent strategic policy towards Turkey is "no". The longer answer is that for years Sofia either hasn't known how to build one or hasn't bothered to. Turkey was somehow perceived as a "known unknown" - the big South-eastern neighbour, a military and economic powerhouse, with whom Bulgaria had some bumps from time to time, but who was at least reassuringly predictable - in contrast to the unruly Balkans.

That started to change in recent years and in 2016 the change became abrupt - Turkey turned into a different country, quickly and lastingly. The failed coup attempt sent Turkey decades back into the past. The ensuing crackdown and the ambitions of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to concentrate all power into his hands, risking to divide and traumatise the country even more, could turn the clock further back.

The spill over to Bulgaria is already being felt. The last elected government of prime-minister Boyko Borissov was reeling between flexing muscles with unnecessary bravado like expulsions of Turkish diplomats and obediently handing over to Ankara suspected supporters of Fetullah Gulen, the alleged coup plotter. With the current power vacuum in Sofia it is not clear when and if there will be a government able to formulate a concept how to deal with a neighbour that threatens to start exporting chaos and instability.

Best frenemies

The Bulgarian-Turkish relations tend to follow the boom and bust cycle. There was a time when former Turkish Prime Minister Mesut Yilmaz was calling his Bulgarian counterpart Ivan Kostov "my dear friend". Mr. Kostov was smiling at the compliments and the political gestures were complemented by economic promises (never fulfilled). But the honeymoon phase was soon over and in 2000 Sofia and Ankara expelled diplomats of the other country and Turkish imams were banned from entering Bulgaria.

The story repeated itself with Boyko Borissov and Mr. Erdogan. At first the personal chemistry between them was visible - both charismatic and strongman figures, former mayors of the biggest cities in their countries, their terms as prime ministers partly overlapping. But the romance faded away rapidly and Sofia tried to distance itself.

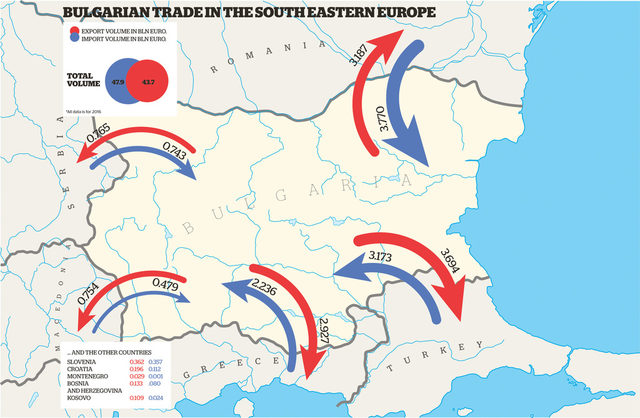

However, Ankara was still adamant to make progress, claiming for example that it has bigger investments in Ethiopia than with Bulgaria. Bulgaria was also deemed to be a possible ally in Turkey's quest for EU membership. Both countries talked for ages about common energy projects, better trade terms, improved cooperation in water management and so forth. History aside, it always seemed that there is nothing to prevent better relationships and improved business opportunities.

There were expectations that the visit of then newly elected prime-minister Ahmet Davutoglu to Sofia in December 2015 - only his third trip abroad after the strategically important for Turkey Northern Cyprus and Azerbaijan - will revitalize the bilateral relations which at that time could be described at best as stagnant. Instead, stagnation burst into collapse.

A morphic dissonance

"I stepped on a Russian mine" was how one of the actors in the Turkish-Bulgarian drama Lyutvi Mestan (former leader of DPS party and current leader of DOST party) described what happened at the end of 2015. The same could be said about the relations between Sofia and Ankara. In the following months a series of clumsy and inexplicable moves followed, worthy of a spy novel.

Several days after the visit the honorary leader of DPS (the party representing mainly the ethnic Turkish minority in Bulgaria) Ahmed Dogan delivered a pro-Russian and anti-Erdogan speech (claiming by the way that he heard morphic voices that gave him guidance). The formal leader of the party Mr. Mestan (who strongly supported Turkey's anti-Russian moves a month earlier) was not only stripped of his chairmanship, but fled into hiding in the Turkish Embassy in Sofia, claiming threats for his life after the removal of his security detail. A week later Turkey issued a semi-official travel ban for the DPS de facto leader Ahmed Dogan and the MP Deljan Peevski, the informal owner of tobacco company Bulgartabac which was allegedly smuggling cigarettes into Turkey. Then came the tit-for-tat declaring of diplomats persona non grata.

Although there was no objective reason for the worsening of relations, they were allowed to become hostage to the internal political games in both countries. The hysteria in Bulgaria reached a crescendo with the creation of a "temporary parliamentary committee for investigating all the facts and circumstances connected to the allegations of interference of the Russian Federation and the Republic of Turkey into the internal affairs of the Republic of Bulgaria".

The spat between the two countries revealed to what extent the relations between them were still marred by Cold War suspiciousness and domination of the security services on both sides. This, of course, is not a good background to build trust.

The coup attempt in Turkey marked the beginning of the next phase in the bilateral relationship. The sabre rattling in Sofia suddenly stopped and gave way to obediently pleasing all wishes of Mr. Erdogan. "We could have our heads severed but we must not allow a migration wave to take place" declared the PM Borissov in 2016, evidently panicked and desperate. The midnight deportation to Turkey of the alleged Gulen ally Abdullah Buyuk - contrary to Bulgarian courts' decisions, national and international laws - was just the noisiest case in a string of silent extraditions demanded by Ankara. What is more, in a demonstrative manner Bulgaria on occasions sided with Turkey, criticizing the EU for doing nothing on the migration crisis while Ankara was taking all the brunt and doing miracles.

The culmination of Mr. Borissov's impotence was his semi-forced visit to Istanbul on 26 August - the first one for an EU leader after the coup attempt. The declared goal was to negotiate a "bilateral mechanism" for regulating the migration crisis. The reality was that Ankara used Borissov as a messenger to issue an ultimatum to the EU - lift the visas for Turkish citizens or be prepared to face "huge risks".

The poisonous cocktail of Erdogan's ambitions, Kurdish separatism and all the demons born by the Syrian war, is turning Turkey into a battlefield. If the situation there gets out of control, Bulgaria will be hit not only by a migrant wave but also through many other channels - economy, trade, security. Still, it doesn't seem that anybody in Sofia has if not a strategy then at least a contingency plan.

Svetlomira Pavlova is editor with Capital Weekly

The short answer to the question if Bulgaria has a consistent strategic policy towards Turkey is "no". The longer answer is that for years Sofia either hasn't known how to build one or hasn't bothered to. Turkey was somehow perceived as a "known unknown" - the big South-eastern neighbour, a military and economic powerhouse, with whom Bulgaria had some bumps from time to time, but who was at least reassuringly predictable - in contrast to the unruly Balkans.

That started to change in recent years and in 2016 the change became abrupt - Turkey turned into a different country, quickly and lastingly. The failed coup attempt sent Turkey decades back into the past. The ensuing crackdown and the ambitions of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan to concentrate all power into his hands, risking to divide and traumatise the country even more, could turn the clock further back.