I have stressed a number of times that I don't want to simply hear talk about solidarity with Bulgaria. There are a Bulgarian and a European flag flying on our side of the border. It's high time for both of them to earn their place", Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said in his unique edifying tone, standing with his back towards the three-meter high razor wire fence on the border with Turkey. To his right stood Victor Orban, his Hungarian counterpart and a fellow strongman, showing support for what has become Mr Borissov's obsessive cause in the past few months - stopping the refugee influx into Bulgaria.

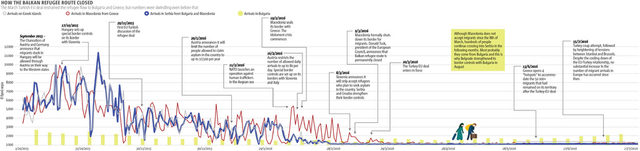

Mr Borisov has highlighted this goal on different occasions and hasn't spared both domestic and EU resources to achieve it. Over 146 million leva (€73 mln) have been invested since 2013 in the border fence, called euphemistically "a protective engineering facility". Army detachments were briefly deployed near the Greek-Macedonian-Bulgarian border in March, when there were fears that the refugees stuck at Greece's Idomeni could head towards Bulgaria. The Bulgarian PM was the first European leader to visit post-coup Turkey in an attempt to make sure that Ankara won't "release a flood of invaders", as the majority of Bulgarian press and many politicians refer to the migrants and asylum seekers.

Migration Becomes a Centerpiece of the Presidential Race

Despite the low number of asylum seekers and economic migrants in Bulgaria panic is growing. Anti-immigrant marches took place in several Bulgarian towns. The protestors were a relatively small number of extreme nationalists but anti-immigrant feelings have started to shape the political debate in Bulgaria. One of the main pivots of the presidential race is the immigration issue, with the government focusing its efforts and scarce funds more and more on border fences and expulsions instead on the much needed education, judicial and police reforms. Mr Borissov is adopting anti-European rhetoric (sometimes not without reason) which will play into the hands of EU-bashers - an attitude that is not very helpful for a country that benefits so much from its membership in the EU.

But the biggest danger of all is the change in mood towards foreigners. Generally, Bulgaria is a hospitable place for foreign nationals who rarely see some of the xenophobic stereotypes existing in other countries. This has helped a lot in attracting foreign direct investments as well as many Europeans, Russians and Ukrainians who found their second of third home in Bulgaria. Reversing this positive attitude may have devastating results for a country that actually badly needs immigrants to counter an exodus of its own nationals for economic reasons and a drop in population numbers. Bulgaria is number one in depopulation in Eastern Europe, a recent UN study found.

Rising numbers

Despite the EU-Turkey deal and the drop in the number of detained irregular migrants to a three-year low, Bulgarian refugee camps and the temporary police detention centers are crammed. In August the police facilities were 80-95 percent over their maximum capacity and the refugee camps of the State Agency for Refugees (SAR) are catching up and are slowly getting packed to their maximum. According to internal ministry statistics, there are more than 6500 people in all of the camps today - a number, unseen since the winter of 2013.

The increased border control in Serbia and the deployment of Frontex officers alongside their Bulgarian counterparts puts pressure on human traffickers, creating a bottleneck for migrants who would otherwise continue their journey to the wealthier countries of Western Europe.

In order to fight this, government pressed its case for creating three additional crisis centers, each able to accept 1,000 people, with the money that Bulgaria received from the EU to protect the bloc's external border. The prime minister managed to draw the attention of European leaders and almost instantly got €160 million emergency funding from the EU security and migration funds, on top of the €72.7 million from the EU's Internal Security Fund (ISF), which Bulgaria stands to receive during the period 2014-2020.

A changing profile

The profile of migrants is also changing. While last year more than two-thirds of the irregular migrants caught crossing Bulgarian borders were from Syria or Iraq, this year Syrians are only 10% of asylum seekers. More and more young men from Afghanistan enter Bulgaria illegally, as they are the most desperate to cross the country on their way to Western Europe undetected. This is a markedly different trend compared to Greece, where the UNHCR still registers more Syrians attempting to cross the Aegean than any other nationality.

Less and less Syrians are trying to cross Bulgaria due to the strengthening of the guarded perimeter around the border and the reported violent pushbacks and harassment by Bulgarian border police over the past three years. The first instance of an asylum seeker killed within the borders of Europe was registered in Bulgaria in October 2015 when a young Aghan man was shot dead by a police officer near the town of Sredets, near the border with Turkey. Many people were found frozen to death on the borders with Serbia and Turkey as well.

The same bad reputation haunts the Bulgarian asylum system. In August, the country drew fire from the UN rights chief, Zeid Ra'ad Al Hussein, who sees 'worrying signs' in Bulgarian regulations for detention of migrants.

Moreover, the number of rejected or terminated asylum procedures increased, especially the latter. More than 10,000 people gave up their applications to be granted a humanitarian or refugee status last year, yet just 644 have been deported since the beginning of 2016. The majority of the rest tried to leave the country.

Political scaremongering

Anti-immigration rhetoric has become norm in the language of almost all mainstream political parties in Bulgaria. Although the president has very limited options to influence the refugee issue, the idea that migration poses a threat is being used by the majority of presidential candidates including the Socialist nominee, Roumen Radev, centrist Tatyana Doncheva, who rides on an anti-corruption platform and even the Reformist Bloc's Traycho Traykov, who has said that Bulgaria shouldn't become Europe's "immigrant ghetto".

Rhetoric isn't the only tool used by politicians, though. In recent weeks, nationalist party VMRO, part of the so-called Patriotic Front, which is the unofficial partner of the governing GERB, used the refugee card in another way. The local branches of VMRO in the Ovcha Kupel neighbourhood of Sofia and in the town of Harmanli, near the border with Turkey, (both housing refugee camps) staged protests against the facilities - and the people inside them. The rallies were endorsed by VMRO leaders - the member of the European Parliament Angel Dzhambazki and the presidential candidate Krasimir Karakachanov - and were attended not by local members of the public but by party affiliates and motor gang members.

Public fears and vigilantes

The fear of refugees has infiltrated the public realm as well. According to Bulgarian pollster Alpha Research, 43% of Bulgarians see the government handling of the refugee crisis as too soft and will prefer a tougher response. What is more, most respondents in Alpha Research's latest survey see international terrorism and refugees as one of the biggest international and domestic threats to the state.

Curiously, refugees are perceived today as a bigger threat than ethnic conflicts. While 34% of Bulgarians saw ethnic conflicts as a threat to peace and just 8% pointed to immigration last year, results shifted in 2016. Only 18% of respondents now believe that a conflict between Bulgarians and ethnic minority groups can threaten the country's existence, while 40% think that refugees may do harm - almost as much as the share of people who see crime as the most significant domestic issue.

Another troubling phenomenon occurred on the Turkish-Bulgarian border. It all began when bTV news channel reported the story of Dinko Valev, a self-styled vigilante migrant-hunter who caught several refugees single-handedly while "taking a drive" on his ATV along the border fence south of Yambol. His actions polarized public opinion in Bulgaria and shed light on several vigilante-style groups which also patrolled the border. Yet, outside of human rights groups and some liberal circles Mr Valev was mostly liked for his actions. Even Prime Minister Boyko Borissov thanked these patrols in a statement: "I personally talked with them [the voluntary patrols] and I thank them. I am sending the director of Border Police to meet and coordinate with them." Some of these groups act like paramilitary organizations proper, imitating military hierarchy and recruiting their members among former Army members. They also boast a vividly pro-Russian, anti-Muslim rhetoric in their online social media channels, which put them on the radar of Bulgarian security services.

A bigger threat to the migrants crossing into Bulgaria, though, is the complete lack of basic social or integrational support. Without such support, no border fence will help the country avoid the segregation of yet another minority, just like its own Roma population.

I have stressed a number of times that I don't want to simply hear talk about solidarity with Bulgaria. There are a Bulgarian and a European flag flying on our side of the border. It's high time for both of them to earn their place", Prime Minister Boyko Borissov said in his unique edifying tone, standing with his back towards the three-meter high razor wire fence on the border with Turkey. To his right stood Victor Orban, his Hungarian counterpart and a fellow strongman, showing support for what has become Mr Borissov's obsessive cause in the past few months - stopping the refugee influx into Bulgaria.

Mr Borisov has highlighted this goal on different occasions and hasn't spared both domestic and EU resources to achieve it. Over 146 million leva (€73 mln) have been invested since 2013 in the border fence, called euphemistically "a protective engineering facility". Army detachments were briefly deployed near the Greek-Macedonian-Bulgarian border in March, when there were fears that the refugees stuck at Greece's Idomeni could head towards Bulgaria. The Bulgarian PM was the first European leader to visit post-coup Turkey in an attempt to make sure that Ankara won't "release a flood of invaders", as the majority of Bulgarian press and many politicians refer to the migrants and asylum seekers.