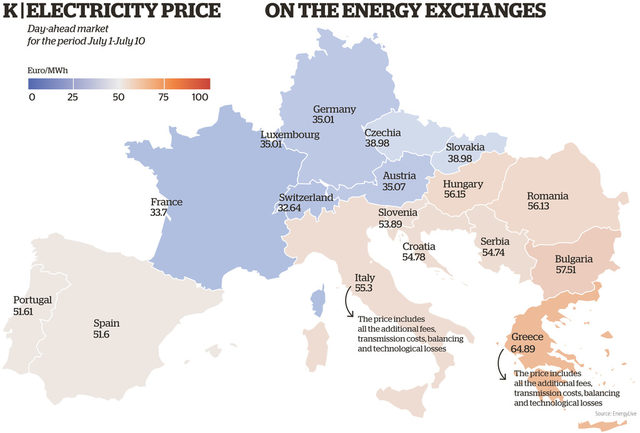

Wholesale electricity prices in Bulgaria have skyrocketed in the past several months and in the first ten days of July they were the highest in Europe. In the last nine months, the electricity on the day-ahead market of the Independent Bulgarian Energy Exchange (IBEX) was 24.5% more expensive in Bulgaria than it was in Germany. In 2018 it was the other way round, with electricity in Bulgaria 21% cheaper than that sold on the German market. This year is in stark contrast to the previous decades when Bulgaria boasted relatively cheap electricity and used it as a magnet for energy intensive manufacturers.

Although there are some fundamental factors behind the rise of electricity prices like the higher cost of CO2 emission allowances and the rise in exports, a strong suspicion exists that several traders have manipulated the market by restricting power supply to drive prices up. This deficit is an absurdity, especially during summer months when there is lower demand for electricity. Bulgaria's energy system has 12 GW of installed capacity, while the average hourly consumption and exports is about 5 GWh - there are more than enough idle generators that could meet it.

How to break an energy exchange

In theory, electricity trading in Bulgaria follows the EU rules which require transparency and free trade. Outside the regulated market (the households and small business) energy producers sell their output on the energy exchange which is open to any trader or big consumer. But different loopholes allow sellers and buyers to influence the price and make backroom deals.

Such a loophole is the bilateral contract platform on the IBEX, which allows a single buyer and a single seller of electricity to conclude speculative deals. If the buyer and the seller are related parties, the former could agree to buy electricity at exorbitant prices, driving prices up on the entire market. That buyer will incur losses but they will be compensated for by the profit of the seller.

Another way to trick the market is by allowing single buyer offers with artificially low prices. State-owned companies are forced to sell electricity to big industrial consumers, who complained last years from the expensive electricity. This decision calmed down the big industry, but drove up prices for the rest.

The third problem is the very thin supply, because power producers cannot (or prefer not to) ramp up production in case of increased demand. In the day-ahead market, creating a minimum electricity shortage (17 MW) can lead to a price hike of over 200%.

If there were enough competing market players, such manipulation would have been impossible. In Bulgaria, however, the two biggest electricity producers - state-owned Kozloduy nuclear power plant, Maritsa-East 2 coal-fired power plant as well as the National Electricity Company (NEC) (all of them units of Bulgarian Energy Holding (BEH) provide between 60 and 63% of the electricity sold on the free market.

Apart from them, there is only one large private producer - a conglomerate linked to Bulgarian businessman Hristo Kovachki. It comprises power plants Bobov Dol, Maritza 3 and Brikel, as well as district heating companies with combined heat and power production in Sliven, Pernik, Burgas, Vratsa, Pleven, Veliko Turnovo, Gabrovo and Ruse. Both groups are producers and traders, which additionally hampers competition.

As a result, duopoly rules the market. After an antitrust settlement with the European Commission, BEH was forced to sell certain quantities on the market but it rarely intervenes when Kovachki's energy group creates deficits. Under the energy exchange rules, all trades are concluded at clearing prices (the equilibrium of the bid-ask process), thus higher prices pushed by Kovachki's group benefit BEH as well, as they allow the state-owned company to pump cash into its unprofitable units.

Difficult imports

Most of these problems would not have existed if traders were able to quickly import electricity from neighbouring countries in moments of deficit and price hikes on the Bulgarian market. In theory, this is feasible, yet in practice, it is almost impossible.

From the existing 3000 MW transmission capacity between Romania and Bulgaria, only 400 MW were available for commercial use in July. In addition, market participants explain that there is no way to buy cross-border transmission capacity for intra-day trade. Most of the capacity is sold on long-term contracts, preventing traders to react instantaneously to dynamic changes in demand.

According to data from the Electricity System Operator, in the period July 1-5 (when prices on the local market skyrocketed), only 10% of the total electricity import capacity was used, with just over 20% from Romania. This, according to the Energy Ministry, means that market participants did not use the transmission capacity they have provided to import electricity, but preferred to export electricity from Bulgaria.

Burned by prices

The cartelization of the electricity market has already harmed Bulgarian businesses. Even before the current turmoil, several metallurgical companies like Greece's Viohalco and Germany's Aurubis reconsidered their plans for expansion in Bulgaria due to the mounting energy costs. Now it is the turn of less energy-intensive manufacturers to feel the pain. Several factories have already announced that they are halting production and employers' associations have joined forces against 'market manipulation'.

Each additional stotinka (half a euro cent) per kilowatt-hour costs the Bulgarian business 170 to 190 million levs per year, the Vice-President of the Association of Industrial Capital Rumen Radev estimated. Such a cost could, at some point, lead to mass production shutdowns.

The instability of the energy market is a bad signal to foreign investors as well. A large investor like Volkswagen, which now searches for a new production site in Southeastern Europe will definitely take into account the unpredictability of energy prices.

What can be done

The first measure should be to prevent producers from selling their output to related traders which is in line with the anti-trust legislation. This is very difficult under the established practice in Bulgaria which considers two companies as related only if they have the same owner (even a close family member is not regarded as a related person). But the energy market can create the precedent that may lead to a change to this faulty logic which prevents authorities from taking action in many other sectors of the economy.

A second measure could be the setting of a requirement for state-owned companies to actively participate in the market. This would also prove difficult because most of the power producers like Maritsa-East 2 were not designed to work on a market with dynamic changes in demand and have no technical possibilities to ramp up production quickly. However, balancing supply and demand is their only chance to survive in the new market conditions and in order for this to happen, modernization is needed.

A third possible policy measure would be to build a functioning capacity market in Bulgaria. It will provide funds to power producers needed to maintain stable energy supply and keep them on the market, irrespective of the wholesale prices. This will incentivise them to sell more electricity on the energy exchange. While this will not drive prices down, it will prevent violent fluctuations and will give some breathing space for more serious reforms. The funds can be found, especially if the government stops wasting money to support well-connected businessmen.

Wholesale electricity prices in Bulgaria have skyrocketed in the past several months and in the first ten days of July they were the highest in Europe. In the last nine months, the electricity on the day-ahead market of the Independent Bulgarian Energy Exchange (IBEX) was 24.5% more expensive in Bulgaria than it was in Germany. In 2018 it was the other way round, with electricity in Bulgaria 21% cheaper than that sold on the German market. This year is in stark contrast to the previous decades when Bulgaria boasted relatively cheap electricity and used it as a magnet for energy intensive manufacturers.

Although there are some fundamental factors behind the rise of electricity prices like the higher cost of CO2 emission allowances and the rise in exports, a strong suspicion exists that several traders have manipulated the market by restricting power supply to drive prices up. This deficit is an absurdity, especially during summer months when there is lower demand for electricity. Bulgaria's energy system has 12 GW of installed capacity, while the average hourly consumption and exports is about 5 GWh - there are more than enough idle generators that could meet it.