• The least costly way to decarbonize Bulgaria's electricity sector would be to replace outdated coal-fired power plants with renewable energy sources

In the following years the Bulgarian governments will have to take decisions estimated at billions of euro that will affect the country's energy system in the next three decades. These decisions will have to challenge myths about energy security deeply ingrained in Bulgarian society.

The two most important questions concern the affordability of large energy infrastructure projects such as the Belene nuclear power plant that recently resurfaced into fashion once again and Bulgaria's capability of taking the difficult road to decarbonisation without hurting the standard of living of households and the competitiveness of its businesses in the process. If the future Bulgarian governments answer those questions superficially and without a thorough analysis, the resulting policy measures could reverse the positive trend of reducing risks to Bulgaria's energy security observed since the country joined EU or lead to heavy fiscal losses, energy dependence, high energy prices and waste of resources.

The future of Bulgaria's electricity sector

Those two questions were the focus of the report on Bulgaria in the South East Europe Electricity Roadmap (SEERMAP), a study of several scenarios for the future of the electricity sector in the region. The analysis was conducted by the Budapest-based Regional Center for Energy Policy Research (REKK), the Technical University in Vienna, the Belgrade-based Electricity Coordination Center (EKC) and the Hungarian consultancy OG Research in cooperation with the Center for the Study of Democracy (CSD).

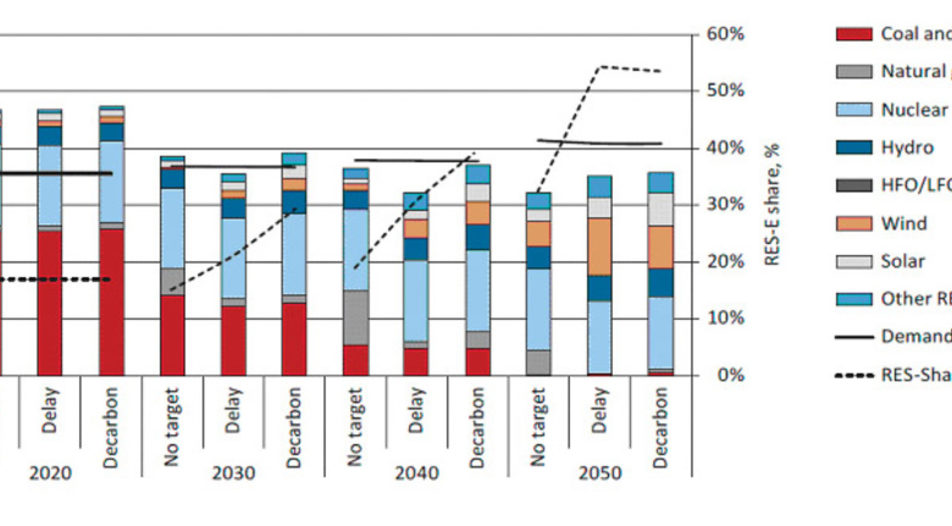

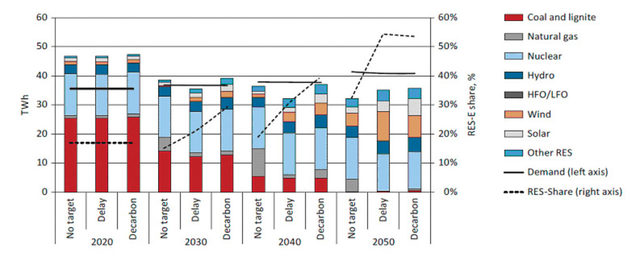

Based on data and modeling used by the European Commission, the scenarios present different options for the decarbonisation of the Bulgarian electricity sector until 2050.

- "No target" scenario. It reflects the implementation of existing energy policies (including implementation of renewable energy targets for 2020 and construction of all power plants included in official planning documents) combined with a rising CO2 price, but no CO2 emissions reduction target for 2050 in the EU or non-EU countries;

- "Decarbonisation" scenario. It reflects a long-term strategy to reduce CO2 emissions by 96.7% (in the case of Bulgaria), in line with the EU emission reduction goals for the electricity sector as a whole by 2050, driven by a rising CO2 price and strong, consistent support for renewable energy sources (RES);

- "Delayed" scenario. It reflects an initial implementation of current national investment plans followed by a change in policy direction from 2035 onwards, a sequence resulting in the meeting of almost the same emission reduction target in 2050 as in the "decarbonisation" scenario. The transformation is again driven by a rising CO2 price and increased support for RES from 2035 onwards.

The results of the modeling work on Bulgaria showed that under the scenarios with an ambitious decarbonisation target and corresponding support schemes for renewable energy sources, the country would have an electricity mix with a 53-54% share of renewable generation, mostly solar and wind, and some hydro by 2050. The best-case decarbonisation scenario would require investment of around 16.5 billion euro but only around 4 billion euro in state support for RES over the next three decades. Meanwhile, the rising prices of carbon, coal and natural gas would lead to an increase of Bulgarian wholesale electricity prices from an average of 34 euro/MWh in 2016 to over 74euro/MWh.

At this average expected wholesale power price in 2050, a new nuclear capacity would not be financially viable, as its break-even cost exceeds 80 euro/MWh. This makes current government plans to go on with the re-start of the frozen NPP Belene project highly questionable.

Also, due to the steeply rising carbon prices, coal- and lignite-based generation capacities would be priced out of the market before the end of their lifetime in all scenarios.

Policy implications for energy security

The results of modeling show that the least costly way to decarbonize the electricity sector in Bulgaria would be by replacing the currently outdated coal-fired power plants with renewable energy sources (mostly wind and solar). In all scenarios Bulgaria becomes a net importer of electricity between 2030 and 2040 and remains so afterwards. By 2050, 22 % of consumption will be covered by imports in the "no target" scenario, while in the "decarbonisation" scenario imports stay at 12% of the total needs.

A rise in electricity prices also carries the risk of increasing energy poverty. In all scenarios, the ratio of households electricity expenditures to income would double to around 8.5 % by 2050. On a macro level, the results suggests that the process of decarbonisation would positively affect growth and the overall competitiveness of the economy if compared to a baseline scenario for the long-term economic development of the country. GDP is around 2% higher on average until 2050 compared to the baseline growth projections.

The laid-out scenarios provide the basis for effective policy decision-making. The conclusions they suggest imply hard choices, which would strain social relations to the limit, and require an extraordinary level of transparency and informed public debate. The governments would need to create an enabling tax and regulatory environment to incentivize companies to risk high upfront costs for investment in RES in exchange for low operating and maintenance costs in the future.

The cost of increased state support for new RES capacities - in the 'delayed' scenario at least - should not be imposed on state-owned electricity companies but should be absorbed by a liquid, fully liberalized power market without long-term power purchase contracts. Delayed action on renewables is possible but it has two disadvantages compared to a long-term planned effort. It results in stranded fossil fuel power generation assets, including currently planned power plants. Translated into a price increase equivalent over a ten-year period, the cost of stranded assets is on par with the size of long-term RES support needed for decarbonising the electricity sector.

Meanwhile, the Bulgarian governments should not rush into seemingly easy solutions for bridging the looming gap in the power market balance by embracing expensive large-scale projects such as the Belene nuclear power plant before comparing the long-term costs related to nuclear energy against alternative low-carbon solutions in which the investment risk is spread more evenly across society. Transparent, solid, data-driven policy decision-making within EU priorities seems to be the only way forward. However, reconciling the demands of the EU long-term policy framework and the socio-political resistance to phasing out coal-fired power plants that employ thousands of people and nuclear power generation could be a very challenging task politically even for the most popular governments.

The alternative is to get stuck into an economically unfeasible project carrying enormous national security risks, whose potential negative impact goes beyond concerns about debt and tax increases and into the realm of geopolitics and long-term sustainability.

*Martin Vladimirov is an analyst with the Sofia-based think-tank Center for the Study of Democracy

• The least costly way to decarbonize Bulgaria's electricity sector would be to replace outdated coal-fired power plants with renewable energy sources

In the following years the Bulgarian governments will have to take decisions estimated at billions of euro that will affect the country's energy system in the next three decades. These decisions will have to challenge myths about energy security deeply ingrained in Bulgarian society.