• The Czech company requested a serious deposit from the potential buyers to squeeze out speculative bidders.

The decision of the CEZ Group to sell its Bulgarian holdings announced in January is an example of a foreign investor with a business strongly dependent of sudden changes in regulations who is considering to withdraw from the country - a rather negative assessment of the government's ability to provide security to investors.

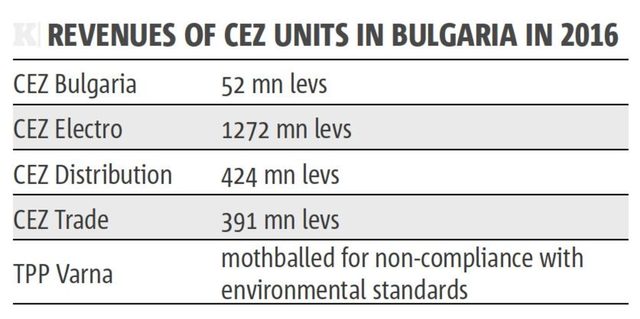

Moreover, the shortlisted candidates willing to buy CEZ's equity in its several Bulgarian units - some of them natural monopolies with guaranteed revenues and almost two billion levs in annual sales - include bidders that are without experience, or are little known.

Why did CEZ decide to leave Bulgaria?

The decision to look for possible buyers of its Bulgarian assets, which CEZ announced in January, came a bit unexpectedly, evident from the chaos in the quotations of its local subsidiaries on the Bulgarian Stock Exchange at the beginning of 2017. The Prague headquarters of CEZ Group issued a statement saying that the decision was based on the interest of several unnamed investors. The company's spokespeople did not elaborate but unofficially CEZ representatives pointed out to worsening investment environment in Bulgaria and pressure to leave the country as the reasons for the decision.

CEZ's business in Bulgaria has not been an easy ride. Almost immediately after CEZ bought 67% of the power distribution company operating in western Bulgaria from the state in 2004 it fell prey to the murky relationship between business and politics in the country. The same happened with the Germany's E.ON and the Austria's EVN, which bought the power distribution companies serving the northeastern and the southern regions of Bulgaria, respectively. CEZ, being a majority state-owned company in the Czech Republic with a similar experience at home, didn't bother to fight back and readily obliged.

First, with the active help of some Bulgarian politicians and government ministers, the state-owned stake in the company (33% until it was privatized in 2011) was represented by people who actually promoted some private interests (like a person who was said to be a driver of an alleged godfather of Bulgarian mafia). As a result, CEZ's image in Bulgaria not only deteriorated but the company exposed itself to further attempts from well-connected entrepreneurs to extort it for privileges for businesses related to its activities.

Next came the government's drive to bring down electricity prices for consumers. The power distribution companies were an easy target.

Their privatization was regarded as a success back in 2004 because of the relatively high prices paid by CEZ, E.ON and EVN. But the success came with a catch - the foreign investors were promised a very high return on their new assets. This was explained with the need for massive investment in Bulgaria's dilapidated electricity grid. At the beginning the rate of return stood was supposed to be at the whopping 16%, which would have gradually decline to 8%, a commonly accepted figure for the natural monopolies.

Those figures became a fixation for the regulator, which began to shrink the share of power distribution companies in the final consumer prices. As a result the rate of return for the power distribution compnis fell to approximtelly 3%, too low for the risks assocciated with Bulgaria.

But the crucial moment came in 2012. The boom of connecting new photovoltaic installations to the grid in the first half of the year was not expected by the Water and Energy Regulatory Commission, which sets the electricity prices for consumers. Since the expenses needed to cover the preferential tariffs of the new renewable energy producers had not been included in the final consumer prices, they threatened to blow a huge financial hole in the energy system. Or to lead to even sharper increase of electricity prices for consumers. The regulator then decided that the distribution companies and the investors in renewable energy sources have to take the bite. What followed was a prolonged legal battle, largely lost by the regulator and the state, which is not over yet.

But the public bashing of the power distribution companies had an effect: they were singled out as one of the main culprits for the increase of electricity prices by 16% in 2012. Tensions heightened in early 2013, when protests were held in several cities against the price hike. Although the power distribution companies had very little guilt about the high price, the then Prime Minister Boyko Borissov threatened to revoke their licenses. The independent energy regulator duly followed the PM's recommendation and attempted to strip CEZ of its license. The authorities conducted numerous investigations and significant fines were imposed, with most of them challenged by the companies and annulled by the court.

The pressure from the authorities made some CEZ officials share in private their conviction that the protests were instigated by a well-connected Bulgarian businessman who wanted to take over CEZ's business in the country.

Finally, in July 2016 CEZ Group said it has filed a request for international arbitration worth hundreds of millions of euro against Bulgaria. The Czech company earlier won an arbitration case against the Albanian government, which had seized CEZ's assets in the country. Albania had to pay a multi-million euro compensation.

Who are the prospective buyers?

It is still unclear how serious CEZ is, as the announced decision to leave Bulgaria might be part of tactics to pressure the government to grant better terms for the company's business. A sign that this might be the case is the price CEZ is said to be seeking (around 400 mn euro) for all of its subsidiaries - close to what CEZ paid in 2004 in completely different circumstances (before the great recession of 2009 and the boom of the renewable technologies). As a result, this might have repelled some of the more serious prospective bidders, like Romanian power supplier and distributor Electrica, which had shown initial interest.

In May, CEZ announced it had shortlisted four bidders. Three of the candidates are Bulgarian companies, while one is Czech.

The first one is the thermal power plant Bobov Dol, which has reportedly offered the highest price. The company has an offshore owner, although nobody in Bulgaria has any doubt that the real owner is Hristo Kovachki. Mr. Kovachki is notorious for buying energy companies that are on the brink of bankruptcy and then squeezing them for profit with hardly making any investment. This, of course, can only happen with good political protection, since his power plants are one of the worst poluters in Bulgaria. When his businesses threatened to go south in 2007, Mr. Kovachki founded a political party, which in theory is without connections to him personally.

The second invited bidder was Sofia-based Inercom Group. It has several photovoltaic installations, but no other meaningful business. Because it is based in the city of Pazardzhik, the stronghold of Delyan Peevski, a MP from the Movement for Rights and Freedoms party (DPS) and an omnipotent oligarch, many see a connection with him but there is no clear link. Mr. Peevski has strong interest in the energy business and in 2013-2014 he controlled almost every deal in the sector.

The third company is a consortium between Turkish engineering holding STFA Yatirim and Bulgarian-based motor oils producer Prista Oil, which probably is the only local contender left who is able to pay the reported price and has an untainted business image.

The only foreign contender is a Czech energy company, Energo-Pro. It already owns the power distribution company that serves northeastern Bulgaria, having acquired the business from E.ON in 2012, and is very active in electricity trade throughout the region.

On hold for now

The sale process has been put on hold for now as expected, with CEZ Group awaiting the outcome of the Czech parliamentary elections due in October.

Then the procedure will be set in motion again but it seems that CEZ is not ready to sell its Bulgarian subsidiaries at any cost. Not only the price CEZ is reportedly seeking, but also the deposit it has asked from the bidders shows that the Czech company is not in the mood to hastily retreat from Bulgaria. In order to submit a binding offer, the four candidates were requested to deposit 5 mn euro each - a threshold some of them will find difficult to pass.

• The Czech company requested a serious deposit from the potential buyers to squeeze out speculative bidders.