It is no secret - prices of essential items, and especially some foods, have soared in Bulgaria recently. So much so that returnees have noticed that prices in Sofia supermarkets are even higher than those in more affluent cities in Western Europe, such as Vienna, Brussels and London. Although it's not a general rule, key products such as eggs, cheese, and butter are significantly pricier in Bulgaria, a fact verified by official statistics and price comparison sites such as numbeo.com.

At the end of 2022, the NSI also reported a record 26.6% year-on-year increase in food prices for November. The increase is a record for the last 25 years. Inflation was 26% for December and 24.9% for January. In fact, food prices have been rising for almost the whole of last year. And if the average Bulgarian consumer did not react until the end of the summer, in recent months he has already started to limit his purchases of necessities, surveys show.

The food issue in Bulgaria is particularly sensitive - the country is last in line in purchasing power in the EU. Compared to other EU countries, household expenditure on food is one of the highest in relation to their total income. Attention has now focused on food producers, importers and traders, and on the supply chains of individual products. And the questions mount: Why is food so expensive? Is it justified or is it speculation? Who is to blame? How can prices be curbed? And what comes next?

Inflationary pressures

In some ways inflation is indeed a global phenomenon. The Covid-19 pandemic squeezed production and disrupted supply chains. As the world opened up, demand grew faster than expected, supply failed to catch up and, by the laws of the market, this stoked prices. In addition, the monetary and fiscal stimulus in the US to fight the pandemic, measures to support business and low interest rates have poured into the market as income.

Lachezar Bogdanov, chief economist at the Institute for Market Economics (IME), explains. "Inflationary tensions erupted in the winter of 2022 with the war in Ukraine and disrupted supply chains. At that time, fear and panic about the coming apocalypse began trading off oil, natural gas, electricity, and commodity prices. With the uncertainty of how much they would cost tomorrow, everyone along the chain - producers, processors and traders - started to take precautions."

Unpredictability. Commodity prices changing within hours. Electricity price increases. Higher wages and insurance. And also increase in prices of ancillary services. All these are listed by manufacturers from different sectors when KInsights asked them about the reasons for their products' price hikes.

Merchants agree - the reasons are the rise in the price of energy and raw materials. Nikolay Valkanov, chairman of the Modern Trade Association, which unites the major retail chains in Bulgaria, explains: "The dynamics in the price growth of basic food groups is close to that in the whole EU. And this trend, common for Europe, is more pronounced in the countries that are closer to the conflict in Ukraine," he says. Ongoing political instability in Bulgaria also doesn't help.

Preemptive price increases and speculation

A small shop owner in Sofia gives his view: "The main thing with prices right now is the expectation of increases - in packaging, in energy, and in logistics. The companies I work with are trying to act preemptively. Last year they were a little late. And they started to catch up at an unstoppable pace. If before they were at least asking if we wanted to sell at their new prices, now they're asking the question ultimatum - these are the prices from the next delivery. Prices are decided only by the one who produces or resells the goods."

He adds that even if cost elements are seen to decrease, people are still keeping prices high as a margin to ward off a potential future threat. "There is already a trend to reduce the prices of inputs, but I don't hear that anyone has started to reduce their prices," he concludes.

Making up for lower profits in the past

Fact is, many consumers are willing to pay higher prices. Lachezar Bogdanov explains: "In recent years, the real disposable incomes of Bulgarian households have grown significantly. Bulgarian consumers have finally relaxed and started behaving a bit more like consumers in rich societies, and this feeds inflation indirectly because there is no pressure on retailers." He says it's only natural that producers, importers and traders, whose margins have been very thin in recent years, have decided to tap into that rising affluence.

Higher food prices also lead to a tangible increase in the wages of the lowest paid and unskilled workers - in manufacturing, trade, services and to a large extent in agriculture. This, in turn, leads to another price hike by businesses which have to compensate for paying staff more. This is creating a price-wage-price spiral, which economists call self-reinforcing inflation. It is seen as a negative phenomenon.

At the beginning of February, the caretaker cabinet promised to wage war on food prices with concrete measures promised within three or four weeks. Minister of Economy and Industry Nikola Stoyanov outlined two possible lines of addressing the issue - dialogue with business and creating predictability for it, combined with massive swoops on unfair trading practices.

The Commission for Protection of Competition (CPC), which is the main regulator of the market, is hardly mentioned by the authorities. Its chairwoman Yulia Nenkova told KInsights that CPC is actively working on the issue, but this requires time and expert work. She adds that they have recently sanctioned supermarket chains Kaufland and Billa for unfair competition (the sanction has not entered into force because the companies are appealing in court). Stoyanov sees better predictability for business through measures such as lower natural gas prices (already a fact), transport services (fuels have returned to levels seen during the first days of the war with Ukraine), and electricity.

The state has levers to regulate prices, but so far has not deployed them. Without a parliament and without the assistance of regulators, who "have little desire to intervene to solve the problem", its main tool is through subsidies and compensation, explains Georgi Angelov, senior economist at Open Society, in an interview with Mediapool.

"The state can bring the sector together and say 'either behave in a market way or there will be no such discounts'," he suggests, referring mostly to compensation for electricity and the abolition of VAT on bread. "The whole idea was for the state to compensate businesses for electricity so that prices don't go up... And if they raise prices, generate excess profits and create inflation - they should be left without support, with the funds going directly to households through tax breaks and other measures," he suggests. "You cannot waste so much money and have no effect on inflation," he adds.

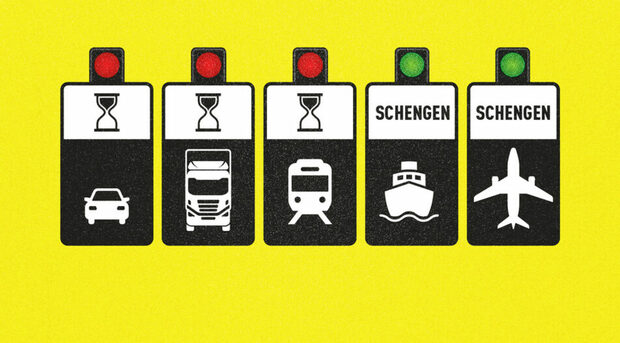

Mr Angelov believes a thorough investigation is required. "If the market is not competitive and if a price in Bulgaria is persistently higher than in neighboring countries, then someone is probably preventing competition. Why can't someone import 20 truckloads of goods from a neighboring country and bring the price down?"

When the price statistics are flashing bright red, the antimonopoly authority should look for a cartel that allows non-market prices, the abuse of market power or import barriers, he stresses. Yet, this is an unlikely scenario. Instead, the market will more likely regulate itself and tame prices as consumers baulk at paying sky-high shopping bills.

It is no secret - prices of essential items, and especially some foods, have soared in Bulgaria recently. So much so that returnees have noticed that prices in Sofia supermarkets are even higher than those in more affluent cities in Western Europe, such as Vienna, Brussels and London. Although it's not a general rule, key products such as eggs, cheese, and butter are significantly pricier in Bulgaria, a fact verified by official statistics and price comparison sites such as numbeo.com.

At the end of 2022, the NSI also reported a record 26.6% year-on-year increase in food prices for November. The increase is a record for the last 25 years. Inflation was 26% for December and 24.9% for January. In fact, food prices have been rising for almost the whole of last year. And if the average Bulgarian consumer did not react until the end of the summer, in recent months he has already started to limit his purchases of necessities, surveys show.