There is this (in)famous phrase in Bulgarian: "няма хора," which literally translates to "there are not enough people." It is used to describe the chronic absence of enough qualified and motivated workers, especially in the aftermath of the mass migration Westwards after the fall of Socialism in 1989. It is debatable whether the exodus of capable employees was mostly due to the attraction of immigration or Bulgarian employers' inability - and unwillingness - to provide them with good remuneration, but the result is indisputable - Bulgaria has lost a huge chunk of its working-age population.

And while this did not seem to be such a big issue in the years of relatively high unemployment rates, in the last decade the country's employers have finally come to realize that the "няма хора" problem is really catching up with them

The hurdle on the road to post-pandemic recovery

In the aftermath of the Covid-19 pandemic, businesses began seeking ways to improve and grow their operations, but while vacancies are increasing, the people to fill them simply aren't there. According to data from the Employment Agency from June of this year, 70% of businesses are struggling to find new employees, but still have plans to grow their teams.

The situation employers find themselves in is very delicate. Experts explain that the pandemic created the perfect storm that put employees in the driver's seat for the first time in decades. On the one hand, business leaders found themselves required to meet demands for flexible working arrangements and a better work-life balance for their workers if they wanted to keep them. On the other, they had to continue providing competitive remuneration against a backdrop of rising inflation in order to succeed in attracting new, and retaining, current talent. According to a recent survey by ManpowerGroup Bulgaria, 71% of employers plan to increase salaries by the end of 2022 to retain their people. But this is just a snapshot of the state of the labor market - the problem of not having enough and qualified staff has deep roots.

Problems start with academia

The path to the labor market starts with education. Logically, with a declining population (by nearly 80,000 people per year and by almost 900,000 in ten years according to preliminary data from the national census) and a low birth rate, the number of pupils and students is also declining. This year there is a university place available for almost every student. This is because there are more university places than applicants, which means entry is easy - way too easy, in fact.

It is not news that for years there has been a serious shortage of sufficiently qualified staff in the labor market as well. And the ease of university admission is creating concern among employers that quality graduates will be harder to find. According to Tomcho Tomov, director of the National Center for Competence Assessment at the Bulgarian Industrial Association (BIA), there are currently about 200,000 specialists needed in all sectors of the economy, and forecasts are that in 5-6 years they will double.

Employers as the new teachers

Maria Stoeva from ManpowerGroup - Bulgaria says that due to the insufficient - and often inadequate to the needs of the market - education, many companies are increasingly hiring people without university degrees because they prefer to train them in-house.

ManpowerGroup consultants are receiving more and more requests from companies to set up joint academies. The HR specialist says these types of partnerships have never been part of the company's business line and niche market, and now it is imperative because "even if they have a university degree, the candidates just don't bring the skills". It no longer matters whether a job candidate is a graduate or not - everyone has to go through training to learn the nitty-gritty of the job. Here comes the function of employers as training institutions. For many, this is strange, but increasingly they understand that this is the way forward because "there is simply no other way."

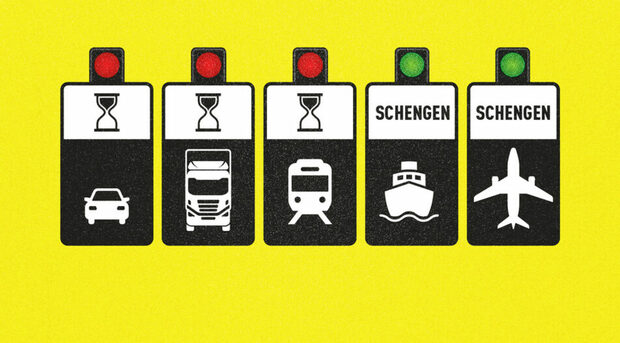

Immigration continues to hurt

Not only is there a lack of sufficiently trained specialists in the country, but the trend of Bulgarians choosing to work abroad is continuing and even accelerating despite the nearly two years of restricted travel because of the Covid-19 pandemic. Maria Stoeva says that many Bulgarians go abroad for seasonal work, many people also continue not to look for permanent work in Bulgaria and prefer to go to Germany, the UK and Spain. This creates a problem not only recruiting highly skilled professionals who are known to be difficult to find - IT specialists, doctors, nurses, but also in recruiting low-skilled workers for the manufacturing sector, for example.

The natural solution to keeping people in the country is to raise wage levels, which Ms Stoeva says has already begun happening at a "good pace". She believes that at some point, when wages in Bulgaria reach the "average European level," the number of people seeking work abroad will decrease. But currently, no matter how fast wages rise, inflation seems to be eating them up, and employees cannot practically notice the effects of these company policies. On the one hand, employers find it difficult to keep up with the wage increase at the rate they would ideally want (because of increased prices of electricity, fuel, etc.) and, on the other hand, even if they do raise them, people do not see a serious difference in their day-to-day life. "At the moment, we are in a vicious circle that is very difficult to break out of in the short term," Ms Stoeva adds.

Brains (and hands) draining across the border

The problem of the so-called brain drain is another serious challenge. The more developed economies invest a lot in attracting talent, but the trouble is that this is also happening in areas such as healthcare, which are vital for Bulgaria, Tomcho Tomov says. The expert believes that retaining people can only be done by raising wages and improving working conditions so that these people can develop. Regarding seasonal workers, Mr Tomov notes that the problem is very serious, as the issue of providing the possibility of flexible hiring, daily hiring, same-day payment of wages, etc. has not been addressed for many years.

Tomov also notes that businesses should learn a lesson when it comes to crisis management. A big mistake of employers, according to him, is that the first measure at a time of a recession always appears to be to slash workers. "They need to look for other solutions. The Covid-19 crisis has shown the tourism sector, for example, that once employees are made redundant, they reorient themselves and don't go back to their firms."

How to turn the tide?

In order to slow down the negative trend, the state should facilitate the import of workers from third countries, the HR experts seem to agree.

On the other hand, traditionally, the industry is looking for professionals with secondary vocational education. Although there has been a marked increase of interest in this type of education in certain areas, it is lowest exactly where the shortage of personnel is most sensitive - very few young people want to become machine builders/operators, specialists in the food industry, chemists, biotechnologists and builders. Instead, Bulgarian students keep preferring language, economic and financial high schools and the trend of young people fleeing industry persists.

The solution to this problem goes through a set of policies that have to be taken up by the state, local government and business. The BIA has developed several projects related to active aging - for people aged 50 - 60+ to create jobs and working conditions to keep them in work. Mr Tomov says these people are a great workforce reserve because they have potential, and with life expectancy increasing, they can be kept as part of the workforce. Businesses have responded well to this BIA initiative, with over 200 companies from 20 sectors taking part.

The picture of the Bulgarian labor market is far from rosy. Businesses struggle to train their employees because often the education they have acquired does not meet their needs, while at the same time the need for new skills is growing fast due to the rapid development of technology. Despite the rise in salaries, many people choose to change employers for reasons such as lack of career development or disrespectful attitudes from management. Employers are rethinking their organizational culture and remuneration policies, while job applicants are looking around for the "best" employer.

The problems facing the labor market are many, and finding the solutions to them will only happen when government, business and educational institutions come together.

There is this (in)famous phrase in Bulgarian: "няма хора," which literally translates to "there are not enough people." It is used to describe the chronic absence of enough qualified and motivated workers, especially in the aftermath of the mass migration Westwards after the fall of Socialism in 1989. It is debatable whether the exodus of capable employees was mostly due to the attraction of immigration or Bulgarian employers' inability - and unwillingness - to provide them with good remuneration, but the result is indisputable - Bulgaria has lost a huge chunk of its working-age population.

And while this did not seem to be such a big issue in the years of relatively high unemployment rates, in the last decade the country's employers have finally come to realize that the "няма хора" problem is really catching up with them