Pursuing reform on a subject on which no one in the country has expertise sounds like mission impossible. Yet the Bulgarian government was foolhardy enough to tackle the introduction of a toll system for heavy vehicles without considering the pitfalls of such an approach.

Four years later, the result is complete chaos.

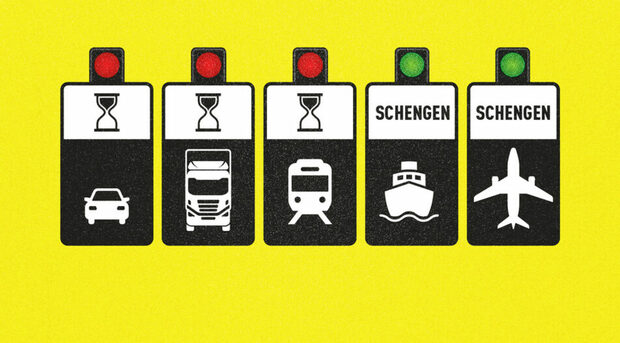

The government began its work on the toll system with a smart and logical step: it signed a consultancy contract with the World Bank which produced a report in 2015. The plan was to implement a toll collection system for heavy vehicles and electronic vignettes for cars over the course of two or three years.

Everything would have been great if only the government had followed the consultant's advice. However, the whole process has been hopelessly botched by the government. The implementation of the first part of the reform, the introduction of an electronic vignette (something quite simple, especially compared to the toll system), was a disaster.

All of the deadlines, the promises of billions of levs per year intended for road investments, as well as other organizational details and the procurement contract's clauses, have changed over time. It transpires that neither of the responsible institutions - the Road Infrastructure Agency and the Ministry of Regional Development, had the capacity or knowledge to carry out the reform. This led to a series of inept decisions which, alongside greed and disregard for the World Bank's recommendations, derailed the whole project.

A billion false expectations

The government came up with the toll system idea for road cargo transport when it realized that foreign trucks in Bulgaria pay very little compared to Austria, for example. As a result, Bulgaria was - so the theory went - losing out on significant revenues that could have helped to rebuild its crumbling infrastructure.

But instead of restricting the toll system to 10 or 15% of the road network, as in most other EU Member States, the Minister of Regional Development Lilyana Pavlova (2015-2016), and the chairman of the board of directors of the road agency, Lazar Lazarov, opted to incorporate up to 60% of the country's roads in the scheme, omitting only minor municipal ones.

According to the government's estimates, such a high percentage would lead to revenue topping billion levs from toll taxes annually. Politicians were tempted by this impressive windfall, betting that it would go towards the underfunded road infrastructure. They endlessly trotted out the mantra that the money would be used to construct new highways or repair potholed roads. After all, at EU level, Bulgaria is among the countries with the worst quality roads with at least 25% of them in 'bad condition', as the current regional development minister Petya Avramova said a few months ago.

A change of heart...or mind

Over the course of the toll reform, things started to change; however, it was unintentional and caught the government agencies and ministries on the hop.

According to the procurement contract signed with Kapsch, the Austrian firm chosen to execute the project, the toll system had to be in place seven months after the start and all tests had to be completed by September 2019, so that it could start operating at full capacity by then. Yet all deadlines turned out to be, more or less, false. In September 2018 the road agency signed a strange annexe to its contract with Kapsch. The annexe (possibly in breach of procurement legislation in Bulgaria) changed a large part of the original conditions.

In the beginning, the plan was for the contractor to build the toll system and receive payments after it was ready. However, the annexe changed the payment schedule in favour of Kapsch. Half of the contract's value, or 90 million levs, was paid out in May, while the initial stipulation was that 40% of the whole sum would be paid when the e-vignette system started working and all control points for the toll system were built. By August, a large number of them had yet to be assembled.

The new deadline was August 16, when the system had to be fully implemented. However, by the spring of 2019, the percentage of toll roads and their fees were still being discussed. On April 1, the Ministry of Regional Development unveiled its concept which envisaged coverage of up to 60% of all roads and high fees when compared to other EU countries.

Transport companies described the proposed rates as "an April Fools' joke". They said the fees were too high, their method of calculation seemed murky, and including third-class roads (which are in terrible condition) was simply insane.

After negotiations between the state and businesses began, it turned out that the government had no hard arguments to support its proposals. Road coverage decreased to 5,900 km or about 30% of the road network. Third-class roads, and some of the second-class ones, were removed from the list. Fees also decreased. Potential earnings fell from 1 billion levs to about 550-600 million levs per year.

All of these discussions were taking place in July, a traditional holiday month, and it soon became obvious that the toll system would not start operating by mid-August. The new deadline is March 1, 2020.

Greed or just incompetence?

It would be a very simple explanation to blame the whole debacle on the transport companies' reluctance to pay higher fees.

On the one hand, road construction has always been a significant part of Prime Minister Boyko Borissov's business card as a politician. He has always portrayed himself as a strong supporter of such projects but they require large sums of money, hence the toll system was always an ambitious aim. So, the first cause of the chaos can be attributed to greed - with the path to the billion levs in revenue littered by insufficient analysis, arguments or impact assessments. Secondly, Bulgaria breached the roadmap provided by the World Bank - namely to decide on the percentage of toll roads first and only then start the procurement procedure. Discussions with the transport sector started far too late - it was tantamount to homegrown sabotage.

Last but not least, it's very likely that the majority of public administration officials had no idea what they were doing with this reform. Their amateurism and disregard for the consultant's advice left them relying on Kapsch. So, the road agency is effectively a work in progress, which is a rather flippant approach when hundreds of millions of levs are at stake.

Pursuing reform on a subject on which no one in the country has expertise sounds like mission impossible. Yet the Bulgarian government was foolhardy enough to tackle the introduction of a toll system for heavy vehicles without considering the pitfalls of such an approach.

Four years later, the result is complete chaos.