One question preoccupies Bulgarians since the fall of Communism - when will they become rich? Well, if Bulgaria can maintain its current rate of economic growth, the answer will be - in 24 years.

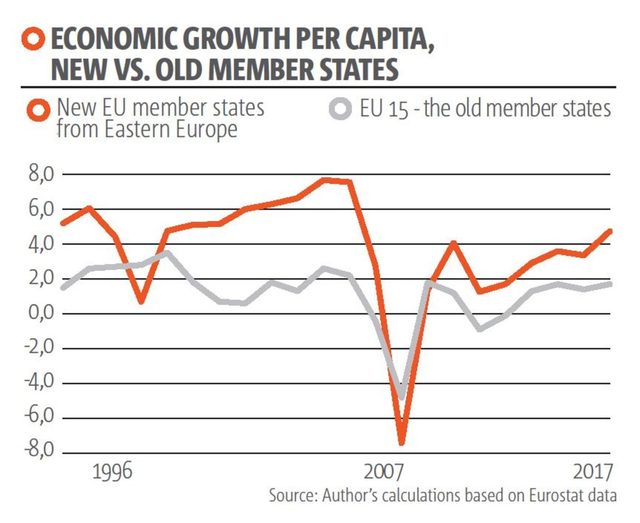

The last two decades were quite successful for the 11 new EU member states from Eastern Europe. Most of them joined the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania in 2007 and Croatia in 2013. However, the accession was not the real start of their European integration. It began as early as the middle of the 1990s, featuring gradual reduction of trade restrictions, elimination of visa requirements, harmonization of rules and regulations, accession negotiations, inflow of foreign investment and pre-accession funds. Integration continued after they joined the EU by giving access to the bloc's labor market; most countries entered the Schengen area, some entered the Eurozone.

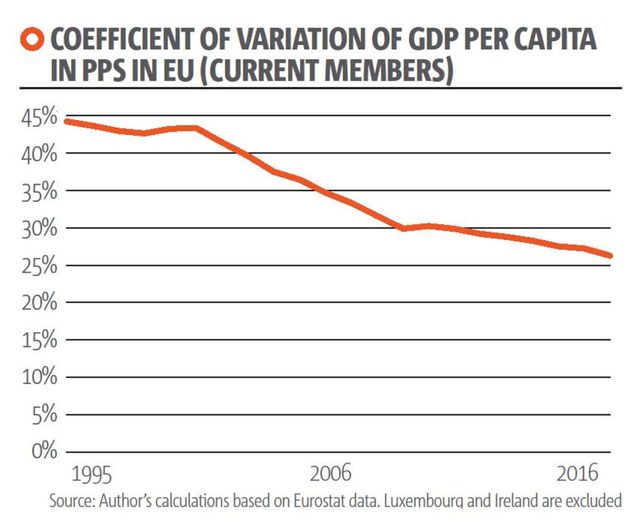

The integration process, among other factors, supported the convergence of real income levels. The coefficient of variation of GDP per capita (the statistical indicator of income disparities between member states) in purchasing power standard (PPS) declined significantly - from almost 45% in 1995 to around 25% in 2016. During this period, the coefficient was on the decline almost every year, with only three exceptions at times of crisis; but these were only temporary interruptions that did not change the trend. For example, in 2000, the poorest country had GDP per capita equal to 25% of the EU average, while by 2016 that ratio had increased to 50%. The reason? Much higher per-capita economic growth rate sustained by the new member states during the last two decades.

When will Eastern Europe become rich?

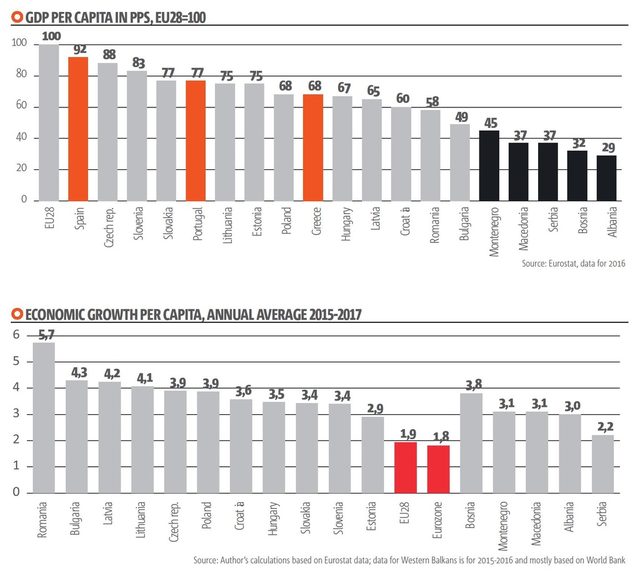

As of 2016 (no more recent data available), six countries from Eastern Europe had already surpassed Greece in terms of GDP per capita in PPS and one or even two more countries look set to become richer than Greece in 2017. By 2016 three Eastern European countries had surpassed Portugal and two more are on the verge of achieving the same, while three others are almost there. However, surpassing Greece and Portugal during a deep crisis is not enough to be classified as rich country. A higher threshold has to be passed.

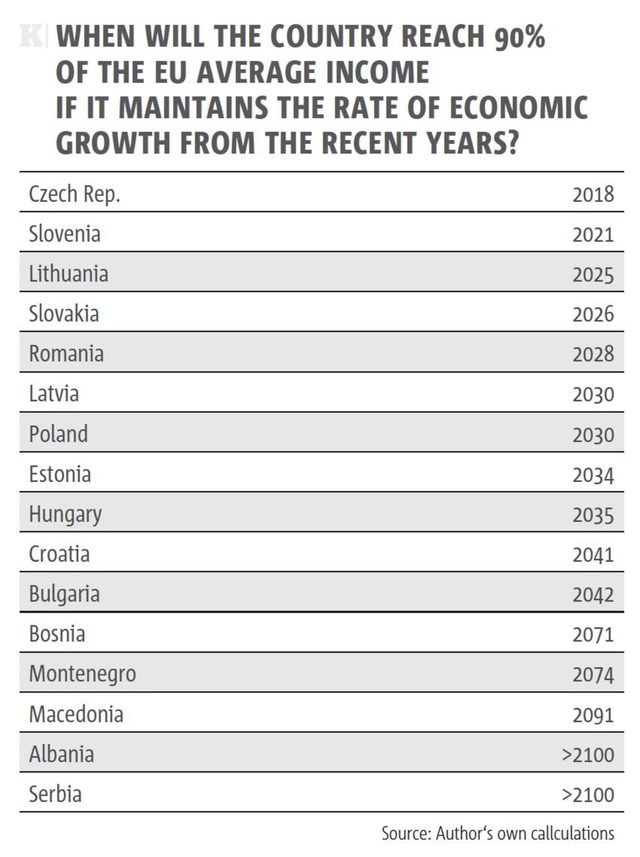

In the current analysis we use 90% of the EU average income (per capita, in PPS) as a threshold. This is roughly where Spain is at the moment. When countries approach and reach 90% of the EU average, the income disparities will be small enough to become invisible and the sizable economic migration from the East to the West ought to disappear. The EU will become more homogeneous in terms of income levels - and thus more similar to the USA.

Catching up in terms of income depends on two factors - the initial level of GDP per capita and the economic growth per capita in the new and old member states (we also include candidates and potential candidates from the Western Balkans). The initial income level is derived from the latest Eurostat data for GDP per capita in PPS (for 2016 - see graph 3). Average economic growth per capita for the last three years is used (graph 4). This is the most recent non-crisis period and it reflects the goal of the analysis to see when Eastern European countries will become rich provided they sustain their current rates of economic growth.

It is not a surprise that the Czech Republic will be the first to reach the threshold of 90% of average EU incomes - the country was already pretty close at 88% in 2016. The Czech Republic will be able to reach the target by 2018. Slovenia is second - if it continues with the current rate of economic growth, it would need three more years. With their current levels of economic growth, Lithuania and Slovakia will need 7-8 more years to catch up. Romania will need a decade to reach 90% of the EU average, but only if it can sustain the extraordinary growth rates from recent years (which is highly unlikely).

If they maintain their current rates of economic growth, Latvia, Poland, Estonia and Hungary will reach 90% of EU income in the 2030-2035 period, while Croatia and Bulgaria will be there in 2041-2042. In other words, Bulgaria will become a rich country in 24 years - provided it can maintain the current rate of economic growth.

There is bad news for the countries from the Western Balkans that are not members of the EU - they will have to wait until the end of the century, or maybe even later, to reach 90% of the EU incomes. Countries from the region that remain outside the EU are lagging behind precisely because they are not in the EU and do not have a clear perspective to enter.

The indicated periods are not guaranteed or certain. They depend on reform efforts that help sustain the current rates of economic growth. Without reforms, growth may slow down, and the catching-up process would take more time. At the same time, countries such as Bulgaria and Croatia have a chance to shorten the period needed to reach 90% of the EU average income. These two countries can join the faster group and reach the goal by 2035 - if they accelerate their economic growth by around half a percentage point per year. This is not completely unrealistic, especially if they seriously take on the path to reforms, continue with EU integration, including in the Schengen area and the Eurozone, and if they can continue to rely on support from the EU budget.

* Georgi Angelov is a senior economist at Open Society Institute - Sofia

One question preoccupies Bulgarians since the fall of Communism - when will they become rich? Well, if Bulgaria can maintain its current rate of economic growth, the answer will be - in 24 years.

The last two decades were quite successful for the 11 new EU member states from Eastern Europe. Most of them joined the EU in 2004, followed by Bulgaria and Romania in 2007 and Croatia in 2013. However, the accession was not the real start of their European integration. It began as early as the middle of the 1990s, featuring gradual reduction of trade restrictions, elimination of visa requirements, harmonization of rules and regulations, accession negotiations, inflow of foreign investment and pre-accession funds. Integration continued after they joined the EU by giving access to the bloc's labor market; most countries entered the Schengen area, some entered the Eurozone.