Secret committees, petitioning, autonomy, independence, secession The Bulgarian media have unleashed a tide of interpretations after an elderly man from the city of Montana said in January that he wanted Northwestern Bulgaria to separate from the country and become part of Romania.

Borislav Kamenov is probably pleased with the media attention he got. But his fairly harmless outburst probably is not the last problem that the central government will face in the country's northwestern region which has been neglected for decades. The region is also the poorest one in the EU, as well as the fastest depopulating part of Bulgaria.

The vicious circle

The decline of cities and regions is neither a new, nor an unfamiliar phenomenon. Just as Bulgaria's 19th century trading centers in the Balkan mountain range gave way to new cities, the former industrial centers of the Socialist era have declined after the closure of the factories there. This is not a process taking place in Bulgaria only. All countries of the post-Soviet area suffer from it, as do many countries in the West.

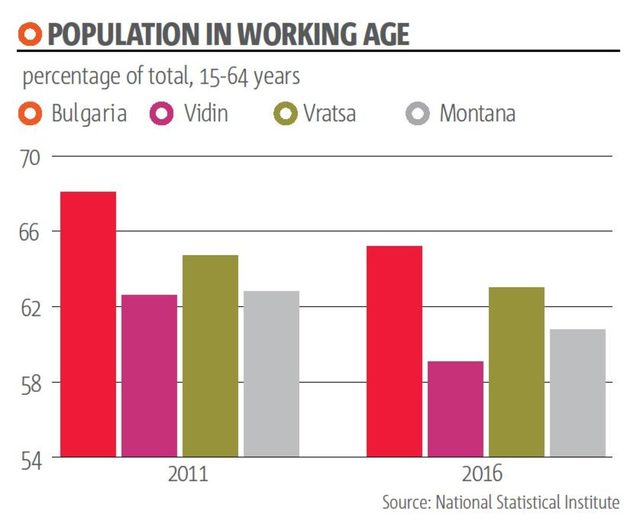

The problems in the three districts that form Northwestern Bulgaria - Vidin, Vratsa and Montana - are aggravated by the fact that the Bulgarian population is decreasing and migrating - to Sofia and to the West. At the same time, the recovery of the living standards in the country from the slump of the late 1990 is hardly felt there. While Bulgaria's population has decreased by 4% compared to 2007 and by 10% compared to 2001, for Montana the rates of decrease are respectively 6.5% and 8%, for Vratsa 11% and 22%, and for Vidin - 12% and 24%. The largest rate of decline is recorded among the representatives of the working-age and educated population, which negatively affects the economic power of the region as well.

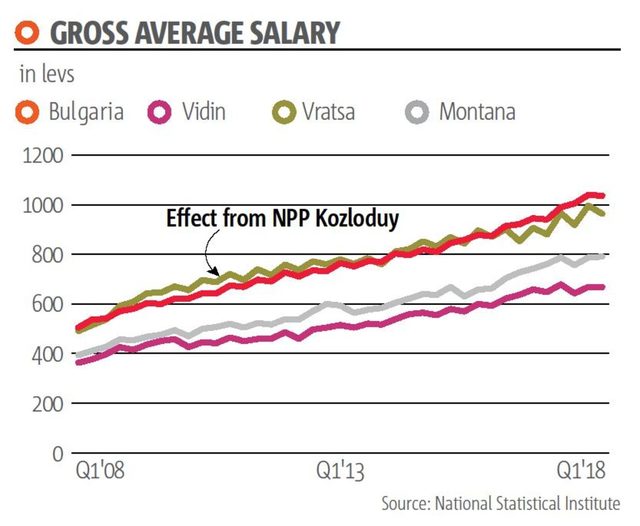

GDP per capita in Northwestern Bulgaria is one-third lower than the country's average, and since 2000 the gap has been widening by the year. The average wage is 20% below the country's average, unemployment is higher, and investors generally bypass the region (see the graphs). The situation in Vidin district is worst: the poor reach almost 50% of the population and the average gross wage has been the lowest in Bulgaria for years.

This closes the vicious circle of poverty - lack of population, lack of investments that could create jobs and boost incomes, and once again worsening of demography. What the policymakers should be very, very concerned about is the long-term deterioration in the capabilities of the region. In all of its three districts - Vratsa, Montana and Vidin, the share of people with higher education is less than 20% of the working-age population. In comparison, a quarter of the people living in Ploviv district (one of Bulgaria's most prosperous) have graduated from university. A representative of the outsourcing sector told us that when the company opened an office in Montana, it easily found people speaking a foreign language but they found it more difficult to adapt to the type of work compared with the employees in the offices in Sofia and Tarnovo. These problems will only deepen further.

Roads, roads, roads

Paradoxically, part of the problem of Bulgaria's northwestern region stems from its geographical location. Even though it is bordering the Danube river (a major European waterway) and two states (Romania and Serbia), the region remains "locked". This is true for many Bulgarian cities in the Danube plain and the border regions: an analysis of the Institute for Market Economics, a Sofia-based economic policy think-tank, shows that the districts of Silistra and Kardzhali suffer from a similar problem.

The main solution lies in improvements to the transport infrastructure. A new bridge over the Danube linking Bulgaria's Vidin with Romania's Calafat (Danube Bridge 2) that was opened in 2013 cannot resolve anything by itself, because the road and rail infrastructure in the mountains of Northwestern Bulgaria is long past outdated. It takes between 3 and 4 hours to reach Sofia from Vidin by car. In comparison, the 230-km distance to Stara Zagora takes just over 2 hours. The trip to the Danube city from Sofia by bus takes as long as the trip to Burgas, on the Black Sea coast, and there is absolutely no point in mentioning trains. It is extremely difficult to see the competitive advantages of a place that you cannot reach easily.

The state is much to blame for the decline of the three northwestern districts. The channeling of almost all funds provided by the EU to southern Bulgaria, as well as the long years of neglecting all transport needs of the northern regions, have led to the division of the country into parts moving at two speeds.

Increased financial independence can help

Improving the transport infrastructure is the most expensive element yet not the only one that can help invigorate the northwestern region. IME has two proposals in this direction. One is related to providing greater financial independence to municipalities by allocating to them of income tax, for example, about 2 percentage points. At present, many small municipalities have insufficient capacity, and if they have to choose between drafting projects to be financed under EU programs and luring an investor, they will choose the first option.

According to IME, another measure that could help poor regions attract investment is to stop the practice of the government to raise by decree the minimum monthly wage in the country (510 levs since the beginning of this year) and the minimum insurance thresholds.

"In Vidin the minimum wage is already around 60% of the average one, so people with low education in the region lose their chance to start work", says IME's Zornitsa Slavova.

Vesela Nikolaeva, a journalist with Severozapazenabg.com, points to further opportunities to infuse life into the region. Tourism is one of those opportunities which can be bolstered by opening additional border crossings with Serbia and improvement of navigation along the Danube. Bulgaria is the only state in the EU that does not invest enough in cleaning and maintaining its section of the river bed, a representative of the European Commission told Capital several months ago. Therefore, Bulgaria even risks losing money. Tour operators have already threatened to stop the few visits to the Bulgarian ports along the river because of the lack of maintenance.

Vili Lilkov, a former MP from the Reformist Bloc from Vidin, told Capital that the biggest political effort to help the region was made by the previous parliament, when a group of representatives of the three northwestern districts supported a development strategy blueprint approved by the ministry of regional development. It comprised a lot of projects, most of which would not have made a major contribution to improving the situation, but it was at least the start of an effort. This initiative died because it was rejected by Finance Minister Vladislav Goranov and Prime Minister Boyko Borissov, Lilkov said. Nothing has come in its place since.

Secret committees, petitioning, autonomy, independence, secession The Bulgarian media have unleashed a tide of interpretations after an elderly man from the city of Montana said in January that he wanted Northwestern Bulgaria to separate from the country and become part of Romania.

Borislav Kamenov is probably pleased with the media attention he got. But his fairly harmless outburst probably is not the last problem that the central government will face in the country's northwestern region which has been neglected for decades. The region is also the poorest one in the EU, as well as the fastest depopulating part of Bulgaria.