#1 How does the currency board function?

The concept of the currency board system is fairly simple: a country's currency is pegged to another currency and the central bank guarantees their unlimited exchange. In practice, the country's domestic currency becomes fully convertible into the anchor currency. This monetary mechanism, however, works only if the country's foreign currency reserves exceed all the money in circulation. If there is a negative balance of payments and the currency reserves are depleted, the money supply needs to shrink.

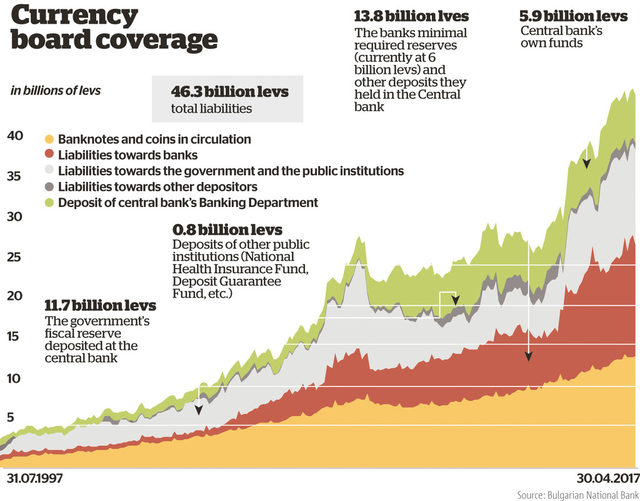

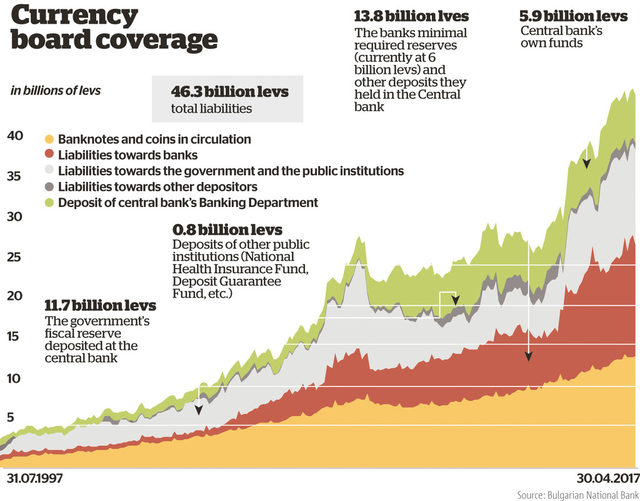

This is also stipulated in the Bulgarian National Bank Act. The central bank should provide full coverage of all its obligations with foreign currency reserves. The main difference between the Bulgarian currency board and the ones described in the textbooks is that the board operating here provides coverage not only of the money in circulation but also of all other deposits held in accounts with the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) - of the commercial banks, the government, etc. This is important in several aspects. First, the direct link with the country's balance of payments is severed and the deficits do not cause immediate shrinking of money supply and contraction of the economy. Moreover, in this way the government can - through its fiscal reserve deposited with the BNB - carry out a quasi-monetary policy by increasing the volume of the reserve. The central bank itself has also retained some instruments for exerting limited influence, such as determining the minimum reserves that the banks are required to hold with it.

Under the BNB Act the central bank is investing currency reserves conservatively - only in securities with a rating higher than АА. In addition, there is almost a full ban on investing them in local entities, including the government and local banks. Across the world, there are examples of more liberal models, which allow investing part of the currency reserves in less liquid and even domestic securities. The purpose of the more conservative approach applied in Bulgaria is to ensure that the domestic currency has real coverage.

#2 How steady is it?

By its design and due to circumstances, the Bulgarian currency board is rather steady. It's difficult to launch speculative attacks against it simply because there is no sufficient number of lev-denominated financial instruments available on international markets to be offered for sale and thus exert pressure on the BNB foreign currency reserves. In this case, the underdevelopment of Bulgaria's debt and capital markets turns out to be an advantage.

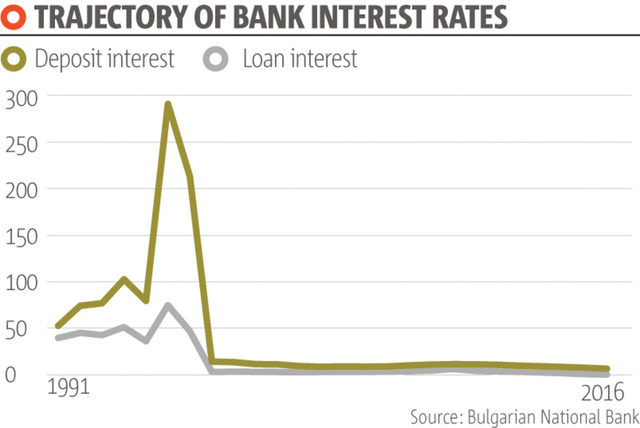

However, there is a financial instrument available in an adequate volume: the deposits in the banking system. Therefore, the collapse of the currency board could be caused by a bank run. This happens when many people withdraw their lev deposits, convert them into euro and rather than reopening their bank accounts they keep the money at home or direct them abroad (through consumption of imports, for example). If this happens, the BNB has a commitment to maintain the fixed exchange rate and buy levs for euro at a EUR 1/BGN 1.95583 rate.

These euro sales will begin to melt down the BNB foreign currency reserves. They now amount to 46 billion levs but actually not all of them are directly available to the BNB. These include the funds of the fiscal reserve, which vary in volume and can be disbursed by the government. The Silver Fund - a buffer designed to maintain the stability of the state pillar of the pension system, is also part of the fiscal reserve. The banks' reserves held with the BNB also fall within this group. Some of them are mandatory but excess reserves, which amount to around 5 billion levs, will drop in case of withdrawals and - in the event of turbulence - may be directed towards other markets.

At the same time, the deposits in the banking system top 66 billion levs, considerably exceeding foreign currency reserves. However, not all of them are denominated in levs and it is difficult to envisage a scenario featuring their complete withdrawal.

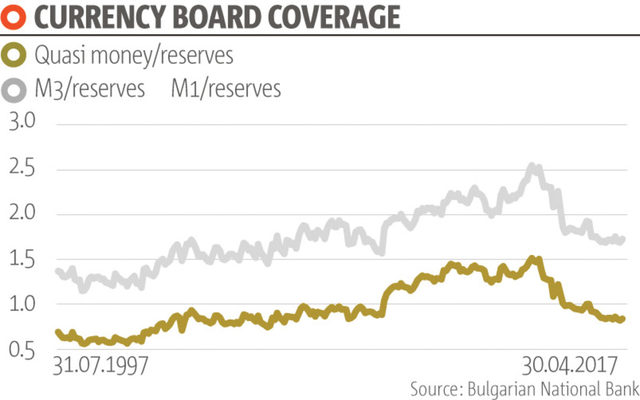

Already at the introduction of the currency board the BNB presented an array of indicators showing the degree of coverage of money in circulation by foreign currency reserves. At present, those indicators are in a rather comfortable zone (see charts) and far from the peak values reached in 2007-2008 and at the beginning of 2014. This is mainly due to the excess liquidity of banks, which are keeping around 5 billion levs as excess reserves with the BNB despite negative interest rates. In any case, the rate of coverage is practically good and there are no concerns about the stability of the currency board.

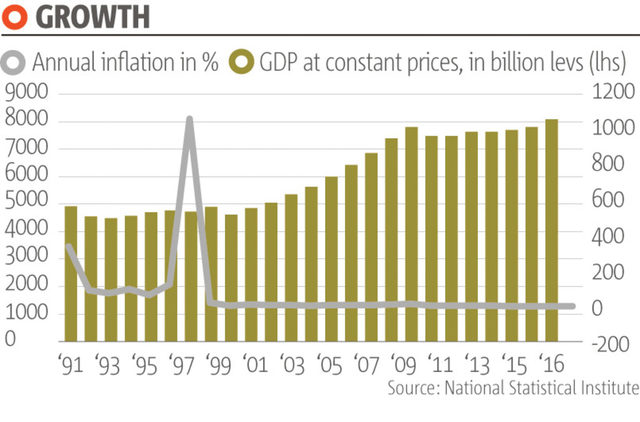

#3 Does it restrict growth?

The opponents of the current system are convinced that it is restricting growth. The pegging of the lev to the strong euro does not allow the domestic currency to depreciate and thus Bulgarian exports are losing their competitiveness. In addition, the lack of monetary policy restricts the opportunities to undertake counter-cyclical actions and promote growth by cutting interest rates when necessary.

The champions of the board, on the other hand, are convinced that its automated operation protects the economy from errors and self-interested actions of politicians. They argue that keeping the currency board in place instills fiscal discipline, while its predictability helps attract foreign investments.

As far as both positions are theoretically supported but cannot be verified in practice, the two camps can be involved into infinite dogmatic disputes. Drawing parallels with other Central and Eastern European countries with or without a currency board systems inevitably entails a danger of making errors. The fact that a country has been developing faster than Bulgaria for the past 20 years can only be partly attributable to the exchange rate of its currency but also to many other factors.

For example, in Bulgaria, the clumsy administration, the dependent regulatory bodies, the sluggish reforms and the judicial system have a far more negative effect on businesses and this can be substantiated by evidence.

Let's take as an example the panic surrounding Corporate Commercial Bank (Corpbank) and the First Investment Bank in 2014. A frequently suggested theory is that had the BNB been authorized to act as a creditor of last resort (which it is not allowed to do under the currency board arrangements), there would have been no problem and it could have helped the banks with liquidity. However, the lev would have actually weakened in such a bank crisis (particularly if the crisis had been addressed with newly printed lev notes), which could have resulted in a higher number of withdrawn lev deposits and people increasingly looking for foreign currency and/or steadier banks. Yet, it should be borne in mind that no central bank can infinitely issue fresh currency notes. Another risk in this scenario would have been the support which the central bank was providing to decapitalized banks in order to avoid admitting the failure of its supervisory activity, thus putting at risk a higher amount of taxpayers' money. To put it in other words, Corpbank could have been saved, at least temporarily, and we would have never known what had happened with it.

#4 What next?

Often, criticism against the currency board is prompted by a wish to invest the foreign currency reserves in the development of the Bulgarian economy. At the same time, the supporters of the currency board interpret every verbal attack against it as desire to appropriate the 46 billion levs balance of the BNB's Issue Department.

In fact, none of the above scenarios could be fulfilled, or not at this scale at least. Whether the country would decide to switch to another monetary regime or adopt the euro, the BNB will continue to have its own balance as the other central banks do (including the ones of the euro area) and to cover the money in circulation with assets - whether levs or euro. The reserves may not remain in their current amount but this does not mean at all that tens of billions of euro will be released.

In the first place, a large part of the funds do not belong either to the BNB or to the government. As of end-May, debt to banks totalled 13.8 billion levs, which constituted the balance of their accounts with the BNB. These are not funds that someone can simply appropriate. Therefore, in the worst case scenario, there is a risk of disbursing most of the fiscal reserve, which is now deposited with the BNB (around 11 billion levs), plus pressure on the central bank to part with a portion of its own funds held by the Banking Department (below 6 billion levs).

The proper public debate upon accession to the euro area should be about the fate of the fiscal reserve. In the absence of a need to guarantee a fixed exchange rate, it can be invested longer- term and with fewer restrictions. As far as these funds are collectively owned by all taxpayers, it is logical to transform them into a sovereign wealth fund as a kind of reserve against future shocks or put them all into the Silver Fund, which is a dedicated sovereign wealth fund in its essence. This already prompts many questions about the rules of its management; whether and how much it should invest in Bulgarian securities; and how to minimize the risks of using it for assisting specific businesses close to the incumbents.

#1 How does the currency board function?

The concept of the currency board system is fairly simple: a country's currency is pegged to another currency and the central bank guarantees their unlimited exchange. In practice, the country's domestic currency becomes fully convertible into the anchor currency. This monetary mechanism, however, works only if the country's foreign currency reserves exceed all the money in circulation. If there is a negative balance of payments and the currency reserves are depleted, the money supply needs to shrink.