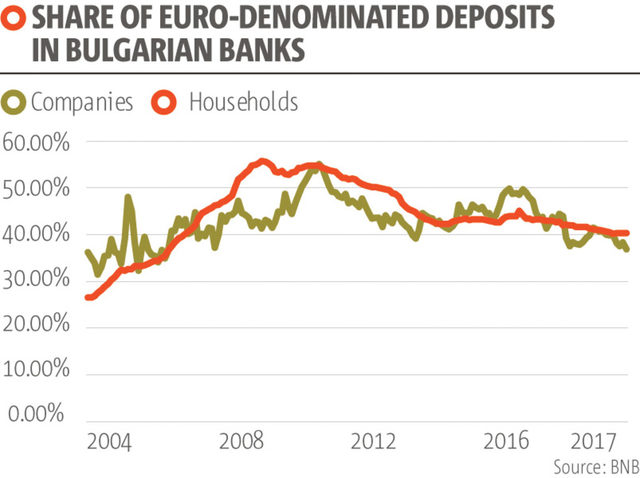

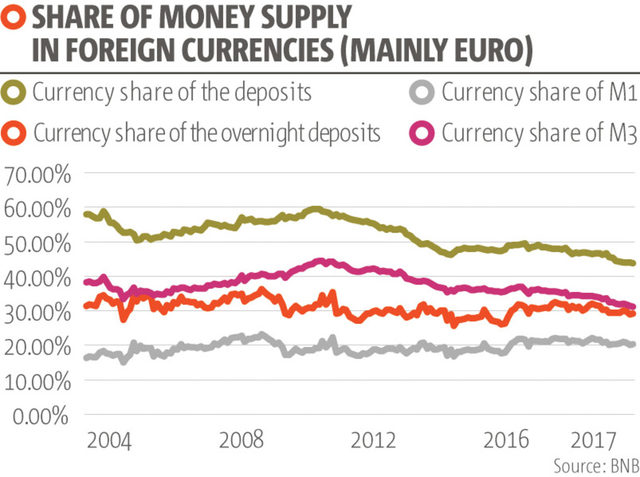

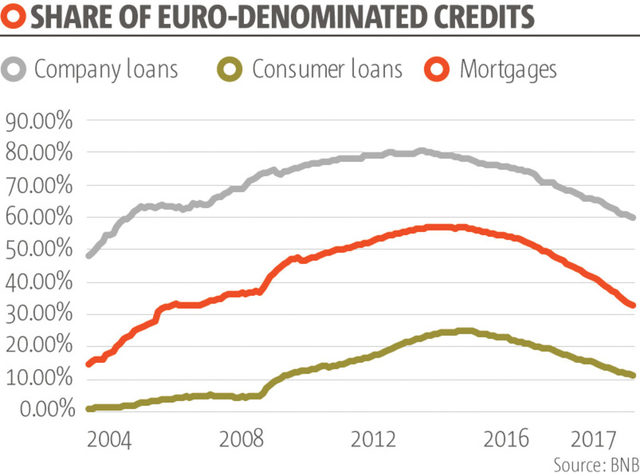

Ever since the euro was introduced in 1999 Bulgaria has virtually adopted it. Although the country has its own currency and you cannot go shopping in Sofia paying in euro, the lev has been pegged to the euro under Bulgaria's currency board system for so long that everybody takes for granted the fixed exchange rate of 1.95583.

Now, 10 years after Bulgaria joined the European Union (EU), the country is making its first tangible steps towards officially adopting the euro. As far back as 2009 then Finance Minister Simeon Dyankov was talking openly about applying for membership of the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), often dubbed the Eurozone's waiting room, but amidst the world financial crisis and Europe's own debt woes, his efforts were doomed to fail and accession to the Eurozone was dropped from his agenda.

Now, the government is talking less but it is sending out enough signals that it is employing very active diplomacy to that end. And probably this is a better strategy since the EU is great at dressing up political decisions with economic rationale. In theory, there are Maastricht criteria and ratios, which a country must meet to qualify for membership of the Eurozone, but in practice everybody knows that accepting a new member of the euro club is something that needs the blessing of Berlin, Paris and several other capitals. Only after that Frankfurt, where the European Central Bank (ECB) is headquartered, enters the game.

Probably a good timing

While a couple of years ago - amidst fears about Grexit - expanding the Eurozone seemed impossible in the short term, now Bulgaria's bid for ERM II is far from being doomed to fail. The UK's decision to leave the EU has altered the mood since 2016, with Germany, France and other big countries at the core of the EU willing to show rapid EU reforms in response to the concerns of their citizens. Hence, any fresh sign of Eurozone vitality is more than welcome. What better signal than new countries knocking on the euro's door? As a result, the Eurozone founders have begun to sound more welcoming and the European Commission has declared it is ready to offer a deal that can't be refused by those outside the Eurozone.

An additional reason for this change of mind is that keeping unprepared countries outside the Eurozone for too long heightens the risk of some of them starting to peel off. The countries in focus are the bad kids in the family - Poland and Hungary, but Bulgaria could also benefit from the new mood. This brings to mind Bulgaria's and Romania's entry into the EU back in 2007 when both countries were accepted despite all their shortcomings as politics and bureaucracy played ahead of economy.

Now Bulgaria is trying to pull that trick off once again ahead of its first presidency of the Council of the EU. The rotating presidency, which Bulgaria will hold in the first half of next year, gives the country new visibility and opportunity to lobby in places that were not very welcoming before. In June Bulgaria's PM Boyko Borisov and finance minister Vladislav Goranov visited Germany where they reportedly secured the backing of Goranov's counterpart Wolfgang Schaeuble. In August French president Emmanuel Macron visited Bulgaria and publicly voiced support. And in between the Bulgarian National Bank (BNB) made promising presentations and meetings at the ECB.

All this raises the odds that after Germany's federal election on September 24 Bulgaria may receive the reward for its diplomatic push and staunch pro-EU stance and be admitted into the ERM II. Given that the admission will entail no obligations for the existing Eurozone members, it could be sold as a piece of positive news: Bulgaria may not be the preferred new entrant (Sweden is), but it will remind the members of the euro area that somebody still wants to join their club.

Of course, such deal is far from done, but it seems there are no strong objections. Admittance to the ERM II doesn't change anything big - the Eurozone will still be at least two years away, with the last entrants having spent about a decade in the exchange rate mechanism. Moreover, Bulgaria's economy accounts for just 0.3% of the EU's GDP, so any possible problems seem well contained. And they are unlikely as the country has low debt-to-GDP ratio and one of the best track records of fiscal discipline in the EU. So, such decision does not look like a big sacrifice, while it will be recognition of Bulgaria's efforts and a stimulus for further reforms.

Shot in the arm

Admitting Bulgaria into the Eurozone's waiting room may prove beneficial as the country's governments tend to push reforms mainly driven from the outside. This is even more true for unpopular measures which are sold domestically as "Brussels demands that...". The last big driver was the EU entry and in the years since 2007 the vigour has somewhat dwindled. That's why a possible ERM II entry and a roadmap to Eurozone membership may spur reform efforts.

While generally beneficial, the ERM II entry will hardly make any measurable impact on macroeconomic variables. Interest rates on government debt may fall slightly, particularly when measured as spreads over German bunds. In addition, the ERM II entry may be seen as rating positive by rating agencies and Bulgaria may shed its last junk rating. While Moody's and Fitch assess the country just above investment grade, S&P rates it one notch below and in June the agency upgraded its outlook to positive.

Probably the strongest effect will be psychological. The entry into the ERM II will be a sign that the fixed exchange rate is here to stay, which will put an end to suggestions to float the lev after 20 years of currency board. Although there is a political consensus among the main political parties (both in power and in opposition) to keep the currency board until the adoption of the euro, every now and then voices emerge, calling for a radical shift. This populist minority claims that the currency board pegs Bulgaria to poverty and investing the currency reserves (about 23 bn euro) abroad drains valuable capital. Entering into the ERM with the lev/euro peg would give Bulgaria one more shield against risk of attack on the domestic currency or voluntary dissolution of the currency board.

Long road ahead

Even if accepted into the ERM II Bulgaria will likely have a long roadmap of tasks before entering the Eurozone. Currently Bulgaria fulfils all the Maastricht criteria for membership regarding the levels of budget deficit, government debt, inflation and long-term interest rates, save for its currency having spent at least two years in the exchange rate mechanism. But then again it will need to prove that its performance is sustainable, e.g. inflation or long-term interest rates are not low just as a result of the global crisis.

One key issue is when the country will enter the Single Supervisory Mechanism. Membership is mandatory for all Eurozone countries, but there is an opt-in for the remaining EU member states. After the 2014 banking crisis in Bulgaria triggered by the failure of the 4th largest lender in the country, Corporate Commercial Bank (Corpbank), there was a wide consensus for applying for SSM membership, which would imply that ECB will take over supervision of the country's largest banks. Three years later and after a system-wide Asset Quality Review and stress tests, nothing has changed officially but now the BNB is not so eager to transfer supervisory control earlier.

And again it all boils down to diplomacy and tactics. Some view application for SSM membership as a strong commitment which would ensure quicker euro adoption. Others argue that if Bulgaria enters both the ERM and the Banking Union, this may block further progress for some time, as it will look like several huge steps are being taken at once and European leaders may adopt a wait-and-see approach. This, however could be an excuse for those who prefer BNB supervision of local banks to last as long as possible.

The most important question, however, is how serious the Bulgarian government is on taking the country into the Eurozone. If its efforts only aim at entering the ERM II but don't target membership of the Eurozone itself, it could be a tactical move to gain some political bonus points at home. It will be seen very soon from the steps the government will take in the fight against corruption, the measures to catch up with the rest of EU in terms of incomes (the so-called real convergence) and the actions to plug the open holes in the Bulgarian financial system - the real impediments to the euro adoption.

Ever since the euro was introduced in 1999 Bulgaria has virtually adopted it. Although the country has its own currency and you cannot go shopping in Sofia paying in euro, the lev has been pegged to the euro under Bulgaria's currency board system for so long that everybody takes for granted the fixed exchange rate of 1.95583.

Now, 10 years after Bulgaria joined the European Union (EU), the country is making its first tangible steps towards officially adopting the euro. As far back as 2009 then Finance Minister Simeon Dyankov was talking openly about applying for membership of the EU's Exchange Rate Mechanism II (ERM II), often dubbed the Eurozone's waiting room, but amidst the world financial crisis and Europe's own debt woes, his efforts were doomed to fail and accession to the Eurozone was dropped from his agenda.