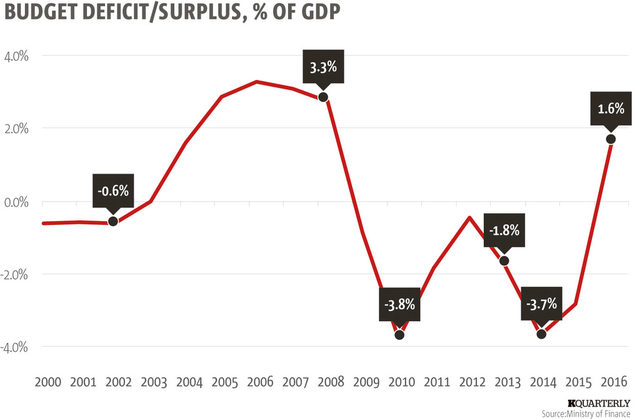

The Ministry of Finance reported a fiscal surplus of 1.6% of GDP in 2016 - the first cash surplus after seven years of persistent budget deficits. This is a dramatic improvement from an excessive deficit of 3.7% of GDP in 2014 and a still relatively high level of 2.8% in 2015. In fact, the fiscal surplus was in a sense surprising - or at least not planned - as the 2016 budget law set a 2% deficit target. What is the explanation for this swift fiscal reversal?

Politics matters

It should be noted that the fiscal surplus was even higher at the end of November 2016 - about 3.8% of GDP - so high that the government approved additional spending in December. For example, it paid in advance 1 billion levs for the National Energy Efficiency Program, although by design the payments should have been made gradually over the next 10 years. With fiscal reserves also record high -14.3 billion levs at the end of November 2016, the government also decided to give the state-owned energy company NEK a long-term interest-free loan of €600 million to pay the Russian Rosatom compensation for the cancelled nuclear power plant project Belene.

Setting aside these one-off payments in December, the underlying fiscal surplus was much higher. One may say the surplus was so high that even an outgoing government could not spend it! The government resigned on 13th November and had seven weeks until the end of 2016 to spend as much as it wanted in advance of the forthcoming elections. But it didn't. In fact, it also achieved a sizeable surplus in January 2017. It seems there was a political decision to limit extra spending and reach a surplus.

This should not be surprising - the finance minister Vladislav Goranov is fiscally conservative (as, indeed, most finance ministers in the last 20 years), but he also had the prime minister's ear on fiscal matters. Mr. Goranov restored the well-established practice of the Ministry of Finance to under promise and overachieve. The planned pace of fiscal consolidation was too slow (deficit cut of only 0.5% of GDP per year after 2014) but it was exceeded in both 2015 and 2016.

The previous government of GERB (2009-2013) - and its finance minister Simeon Djankov - also achieved a significant fiscal consolidation and almost eliminated the deficit despite the economic stagnation. The BSP-led government in 2013-2014 moved in the opposite direction and deliberately increased spending and deficit, but nevertheless they didn't target an excessive deficit. In fact, it was the political instability in 2014 that led to an out-of-control surge in deficit. Thus, the government's fiscal policy is very important, but the real threat is the absence of a stable government.

but economics rules

In 2016 total spending fell by more than 6%, but this was not a result of austerity - in fact national spending increased by more than 6%. The decline came as a result of fewer EU-funded projects since the new 7-year financial framework is at an early stage of development - unlike 2015 when the government rushed to finish all projects from the previous 7-year period before the deadline at the end of the year. In 2015 the government paid for all finished projects - increasing the cash deficit, but the EU reimbursed some of the funding only in 2016, creating excess revenues in 2016. Thus, EU funding artificially increased the fiscal deficit in 2015 and also artificially boosted the surplus in 2016. When the absorption of EU funds gest back to its normal track this effect will disappear.

However, this is not the whole story. There was a real and significant change in the local revenues.

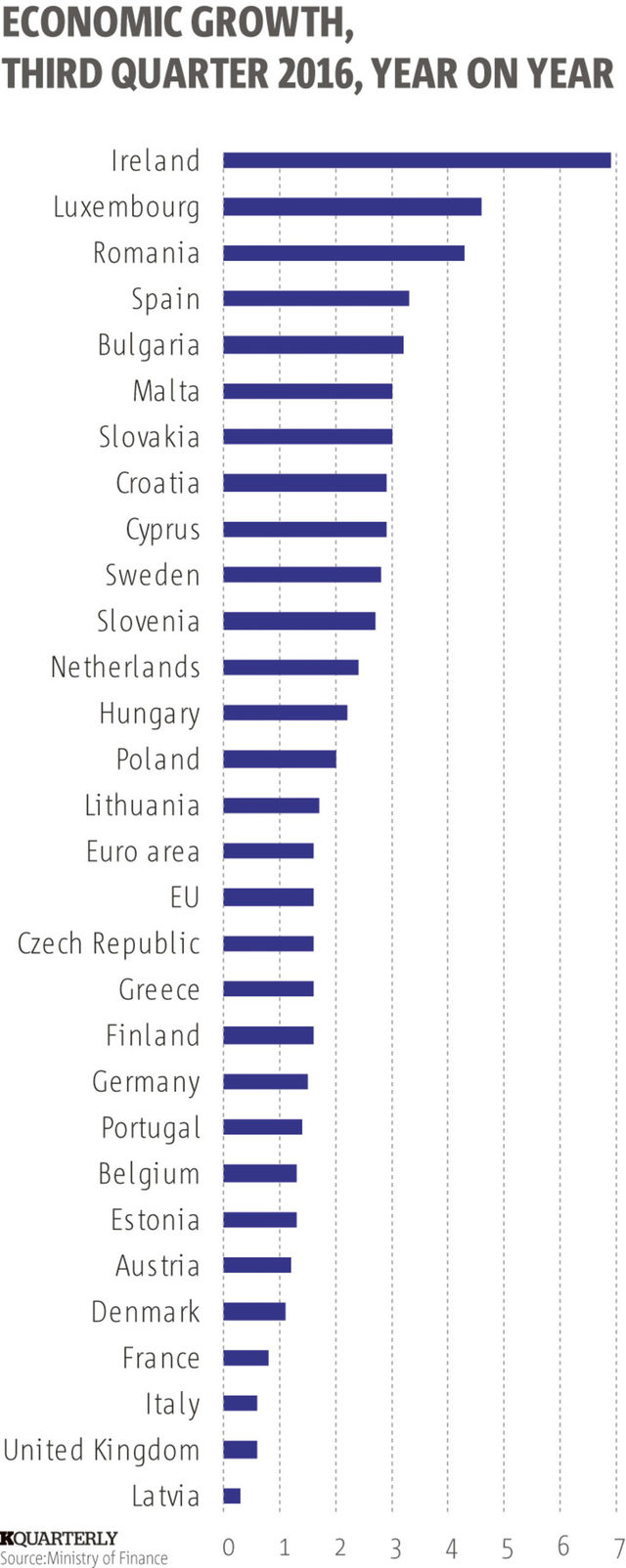

In 2016 both tax and non-tax revenues surged. Tax receipts increased faster than expected, by 8.2%, and reached almost 27 billion levs while non-tax revenues rose by 12.2% to more than 4 billion levs. "The surge in revenue helped take economic growth, at around 3.5% in both 2015 and 2016, higher than forecasted and make it surprisingly stable despite external shocks while employment rebounded.Furthermore, tax collection improved and more than compensated the continuing deflation and credit stagnation. Despite significant resistance, a number of measures to improve tax compliance have been introduced in the past 5-6 years and they finally bear fruit.

It should not be surprising that a strong economy makes it easier to eliminate the deficit. During the pre-2008 economic boom all governments ran sound fiscal policies - and often sizeable surpluses (around 3% of GDP between 2005 and 2008). In contrast, the poor economy after 2008 led to persistent deficits. In 2014 other shocks contributed to the surge in deficit - the collapse of the 4th biggest bank in Bulgaria and the unexpected deflationary pressures.

Is fiscal stability sustainable?

The magic recipe for fiscal surplus in Bulgaria is a strong economy, a stable government and a conservative finance minister. We can be reasonably optimistic about the Bulgarian economy in the short term, especially when the economy of the EU - Bulgaria's main trading partner - is gaining strength. Furthermore, credit growth resumed after two years of stagnation, deflation is coming to an end while exports are surging. However, it is difficult to predict whether a stable government can be formed after the March elections. A prolonged political instability can have a negative impact like in 2014 - although economic fundamentals are better this time.

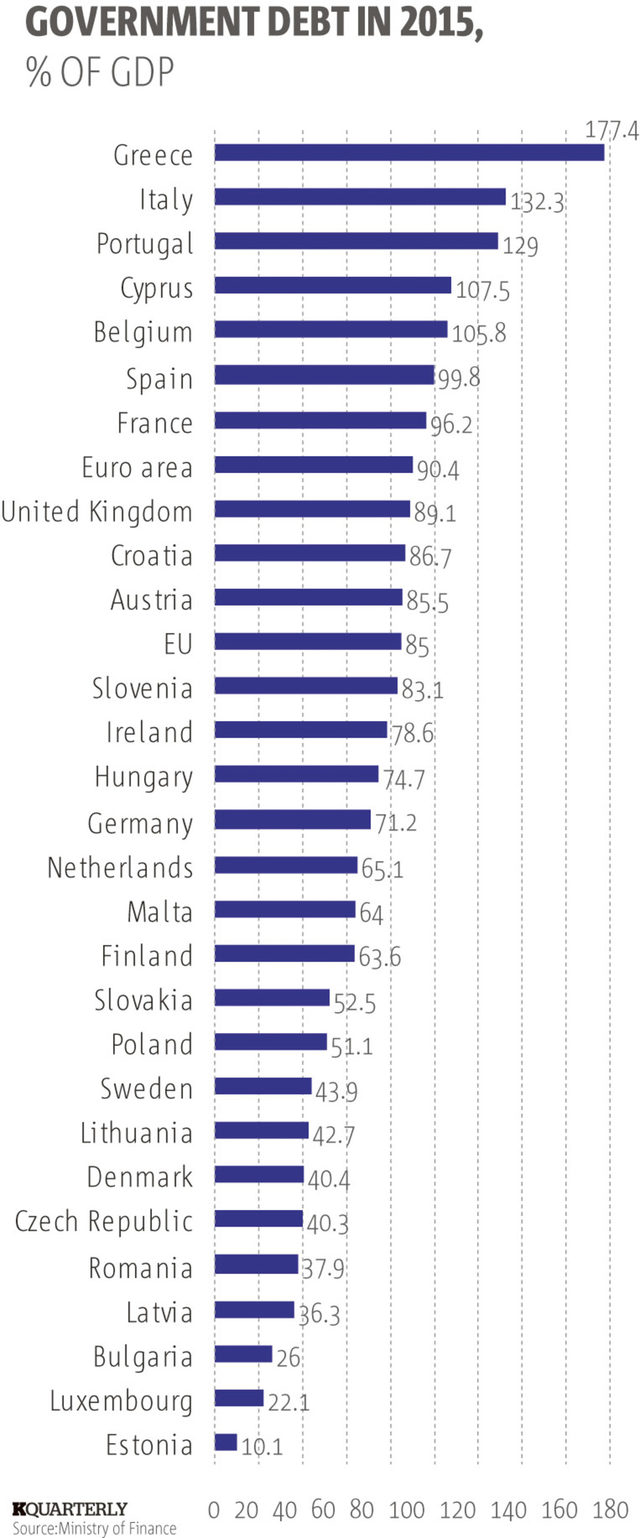

According to the Debt Sustainability Monitor 2016, published recently by the European Commission, Bulgaria moved from the medium to low risk category for long-term sustainability and also currently among the top three countries in terms of low risk in medium term. The reason is simple - Bulgaria's government debt level is among the lowest in the EU and the fiscal policy has been sound for a long time. In fact, Bulgaria has been in the EU's excessive deficit procedure only once, and briefly, unlike most other EU member states. After the 1996-1997 hyperinflation and the introduction of a currency board system the sound fiscal policies receive broad support. Bulgaria is not member of the Eurozone which additionally fosters the market discipline.

The public debt is mostly long-term with fixed interest rates - there is one bond repayment in mid-2017 (already funded) and no other significant payments until 2022. This is a comfortable position that insulates the government from the expected increase of interest rates - as long as it avoids big fiscal deficits.

Low debt, long maturity, fixed interest rates and sound fiscal policy - what could go wrong? Three possible problems: First, a prolonged political instability, fragmented coalitions and populism may increase spending and deficits to unsustainable levels. Second, indebted government companies - especially in the energy sector and railways - may turn into a fiscal problem. Third, reforms are needed to sustain economic growth and overcome the impact of aging and emigration.

Therefore, the most important indicator of fiscal sustainability is the pace of reforms - especially reforms that boost the potential of the economy. Such reforms could include mundane things like the energy sector liberalization, the railways restructuring, the privatization and expansion of Sofia airport, the introduction of road tolls to secure funding for infrastructure investment, increasing tax compliance and the efficiency of public spending. However, it is even more important to focus on long-term challenges: improving education, institutions and investment climate.

Senior Economist, Open Society Institute - Sofia

The Ministry of Finance reported a fiscal surplus of 1.6% of GDP in 2016 - the first cash surplus after seven years of persistent budget deficits. This is a dramatic improvement from an excessive deficit of 3.7% of GDP in 2014 and a still relatively high level of 2.8% in 2015. In fact, the fiscal surplus was in a sense surprising - or at least not planned - as the 2016 budget law set a 2% deficit target. What is the explanation for this swift fiscal reversal?