Forty-five years ago Bulgaria started the construction of the Hemus highway to connect Sofia to Varna, on the Black Sea coast. As at the end of 2019, 30 years after the fall of communism and 12 years after Bulgaria joined the EU, half of the highway still remains uncompleted.

The government has announced plans for the construction of over 300 kilometres of new highways in the next seven or eight years (not counting expressways that are also planned). This would represent almost 40% increase of the existing high-speed road network which, according to the National Statistical Institute, is now 757 km long. Compared to the inactivity of previous decades, these intentions sound quite bold but also to an extent, impossible, as the rate of construction has been much slower. In the last 20 years, Bulgaria has added 235 km of highways.

This may sound impressive but Hungary and the Czech Republic, by comparison, have doubled the length of their highways since joining the EU in 2004. It must be noted, however, that they were supported by considerably larger EU subsidies than Bulgaria's. Croatia, which is half of the size of Bulgaria and has 40% less population, has a 1.5 times longer highway network.

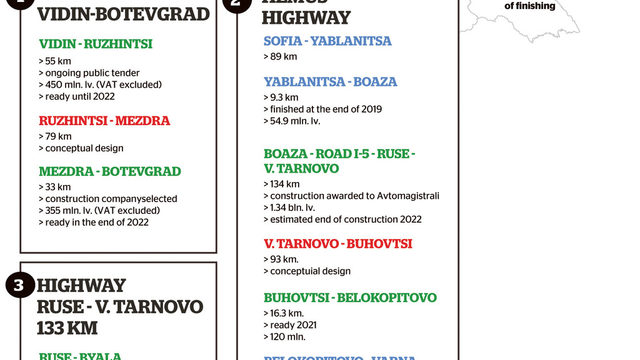

Sections of three highways are in the works at the moment - Hemus, which crosses northern Bulgaria, Struma, which connects Sofia to the border with Greece, and Cherno More, which will run along the Black Sea coast to connect the two big cities there, Varna and Burgas.

The northern dead end

Тhe planned full length of Hemus highway is around 420 kilometres. Less than half of that is finished. Hemus would give a significant boost to northern Bulgaria, as its lack is cited as one of the main reasons why the region is less developed than southern Bulgaria which is much better connected via Trakia and Maritsa highways.

In October 2019, а new section of some 9 kilometres in length was finished. As of 2020 a further 16 km will be completed.

In December 2018 the government awarded a contract worth a record 1.3 billion levs for the construction of 134 kilometers of Hemus highway to state-owned Avtomagistrali company. The chosen contractor does not have experience in road construction per se and did not compete with private companies in a tender. Instead, an in-house public procurement procedure was used, evading the need for open call. Almost a year after the contract was signed there is a permit for the construction of only 1.6 km.

The Minister of Regional Development Petya Avramova has said that the whole length of the highway will be ready in 2024. This sounds like science fiction, at least at this point, considering what has happened until now. The recently completed section of nine kilometers was built by a consortium of three companies. It took them about a year-and a-half to finish the construction. The state-owned firm, which has a questionable capacity to work on its own on highway construction projects, will have to finish 134 km in less than five years. Some of the technical assignments have not been prepared yet and the appropriation of land from private owners for construction works has not finished.

Not to mention that there are still 93 kilometres east of Veliko Tarnovo left, for which there is no funding and no contractors have been chosen for the design and construction.

The road to Greece

Struma highway is a key project which has attracted controversy as well. The seemingly good news is that there is a time horizon for its completion - 2027. Тhere are approximately 30 km left to be constructed of the highway connecting Sofia to the border with Greece, yet that section is quite tricky as it passes through the Kresna gorge, challenging terrain and a national park at the same time. Bulgaria needs over half a billion euro for this stretch of Struma highway. The cost is so high because the project includes tunnels, viaducts and bridges.

Besides the ecological challenges, there are financial problems.

The construction of the whole highway is financed from the EU structural funds and Brussels insists on a clear timetable. The government's Road Infrastructure Agency (RIA) applied for 267 million euro from the current 2014-2020 EU budgetary program in August. Not only was that slightly late, but also the amount is a small part of the financing needed for the project. This is because Brussels will only pay for work done until the deadline of the operational program in 2023. However, the European Commission still has not approved any money for that section of the highway.

The ecological issue is just as important. According to environmental organizations, RIA's plan to use the existing road E79 (which is not a highway) in one direction and to build a new road east of the Kresna gorge in the other is unlawful. The Kresna gorge is a protected area and using the existent road as a part of the future highway will have detrimental effects on nature, because traffic will inevitably increase. The highway is part of the pan-European Corridor IV which starts in Germany and reaches Greece. Traffic through the gorge will be devastating for nature there, environmentalists argue. The European Commission has also expressed some concerns about the environmental impact.

The most scandalous element of the negotiations about the financing was that the project which passed an Environmental Impact Assessment is different from what RIA intends to build. The European Commission noticed the difference in the number of tunnels and bridges and asked for additional information in October. There is no public information as to whether Bulgaria has replied and, if so, what it said.

In short, Struma's future is as vague as that of Hemus.

Driving with a seaside view

Cherno More highway, a project that had long been pushed to the side, was also resumed. At the end of November RIA collected the bids for an extended conceptual design - an assignment having an estimated cost of over 14 million levs.

Only 10 kilometres have been built out of Cherno More's potential length of 95 km and they are located at the northern end starting in Varna. The highway can be considered essential to Varna's progress. Burgas already has connections to the rest of southern Bulgaria and Sofia via the Trakia highway, while the northern seaside city is isolated as neither Hemus nor Cherno More, have been a priority until now.

After a contract is signed, the selected firm will have a year to complete the task of giving three options for the highway's route. Yet, it is early to forecast when the highway will be built. The start of a tender procedure for an extended conceptual design does not imply that the project will follow a strict schedule and may be finished within a reasonable deadline.

For example, another big project - the construction of a tunnel underneath Shipka peak in Stara Planina mountain near Gabrovo that is intended to create a fast connection between Bulgaria's north and south, will be a lengthy undertaking. The contract for its extended conceptual design was signed in 2014 but construction is expected to finish in 2025. Or at least this is the most recent deadline because tenders are still ongoing.

Second, there is no money provided for the seaside highway. According to the government's integrated transport strategy to 2030, Cherno More will cost around 430 million euro. It needs to go through challenging mountain terrain in the eastern parts of Stara Planina.

In 2016 RIA intended to set aside financing for the project from EU funds but the idea never materialized, because Struma has been eating up all the available EU funding. The construction costs will most likely be covered by the state budget or RIA will apply for European funding in the new programming period 2021-2027.

Forty-five years ago Bulgaria started the construction of the Hemus highway to connect Sofia to Varna, on the Black Sea coast. As at the end of 2019, 30 years after the fall of communism and 12 years after Bulgaria joined the EU, half of the highway still remains uncompleted.

The government has announced plans for the construction of over 300 kilometres of new highways in the next seven or eight years (not counting expressways that are also planned). This would represent almost 40% increase of the existing high-speed road network which, according to the National Statistical Institute, is now 757 km long. Compared to the inactivity of previous decades, these intentions sound quite bold but also to an extent, impossible, as the rate of construction has been much slower. In the last 20 years, Bulgaria has added 235 km of highways.