Varna, Bulgaria's third-largest city, displays a peculiar mix of charm and difficult character. It functions on overdrive in summer, then hibernates until the next. Its most valuable asset is the sea, yet it enviously looks west toward the capital. It resents its reputation of being a "captive" to powerful local business groups but it never manages to properly highlight its successes. The "summer capital of Bulgaria" tag is insipid, but Varna believes it confidently. Not only because its history spans far beyond the Bulgarian state, or because it used to be a meeting point for merchants from Genoa and Dubrovnik, but because today it has reasons to be optimistic.

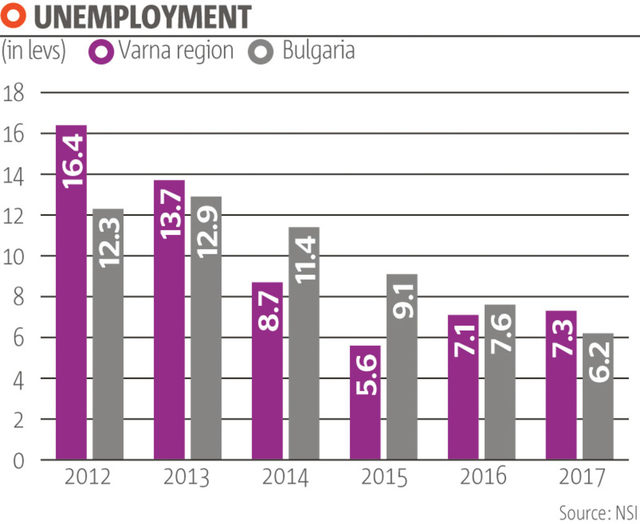

Its seven universities and 28 000 students imbue it with youthfulness and energy. Tourism brings cosmopolitan city dynamics. Even though it lost the race for the title "European Capital of Culture 2019" (a city in the EU designated to host a series of cultural events with pan-European dimension), it still boasts a cultural life that few other Bulgarian cities can match: the oldest music festival in Bulgaria called Varna Summer, the world's only international ballet competition, the International Graphics Biennial, its film and theatre festivals, and last year - even the MTV Varna Beach party. Тhe city's economy is growing, unemployment is falling, and its population increases every year. This is how Varna's "tarnished image" - the feeling among the locals that their city is trailing behind its peers, turns out to be more of a PR and management issue.

The eternal battle

The competition for the title of the cultural capital of Bulgaria is a continuation of a long-running dispute between Varna and Plovdiv. While Varna lags behind Sofia, it doesn't appreciate the third place. At the end of last summer, a colourful T-shirt in a store in Plovdiv's Kapana district delivered yet another blow to the bleeding heart of Varna. The print behind the shop window shouted: Make PLOVEdiv, not WARna.

"It is ingenious, yes! In the eternal battle between Plovdiv and Varna, the print has put us ahead - 1:0," laughs Ivaylo Dernev, editor of Plovdiv's website Pod Tepeto. "But these are the prejudices that get in the way."

For him, the wordplay is more of a ricochet off the last 15 years when the seaside city was in a stupor. "For me, Varna is green parks, architecture from the beginning of the 20th century, the sea, the feeling that there's no boundary in front of you when you stand on the shore. Everything else - the corruption, the political and economic monopoly that Varna went through, is familiar to me. Plovdiv experienced the same thing, maybe even worse, but one impulse sufficed to precipitate a change. In Varna, I always get the feeling of enormous potential."

The way out of the predicament

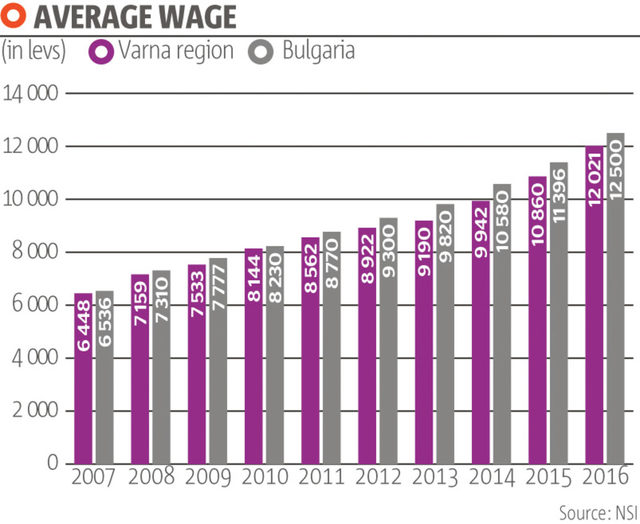

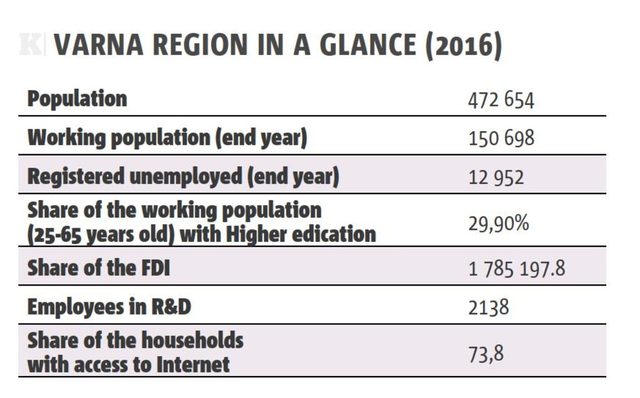

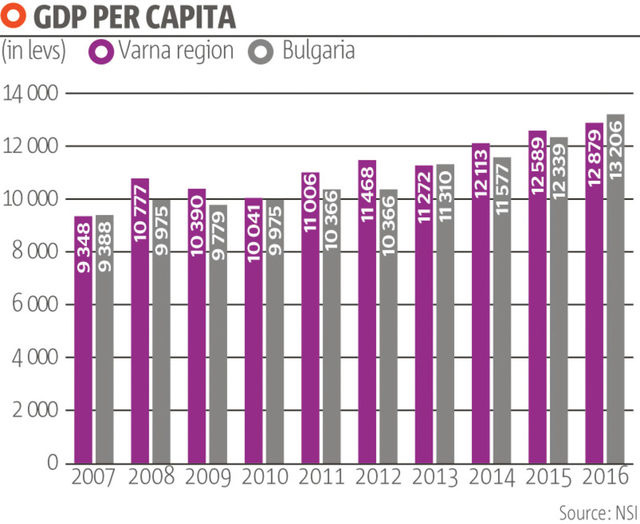

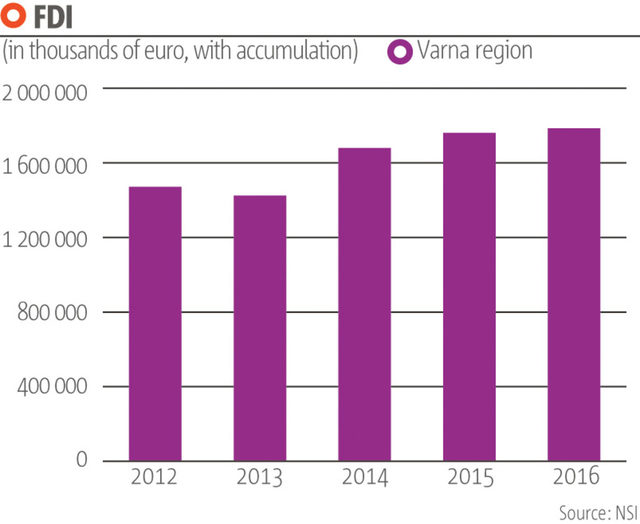

According to 2017 data from the Institute for Market Economics (IME), economic activity has grown considerably in Varna over the past 5 years. Cumulative growth was 20%, while foreign investment increased by 28%. The latest IME research indicates that Varna's average monthly wage of 1062 levs is second only to Sofia's.

IME's analysis also suggests that the demographic and education trends in the city guarantee its stable development. Varna is among the few economic centres in the country and its population swells due to the considerable inflow of people from the surrounding regions because it's the indisputable star of northern Bulgaria. People of working age constitute 63% of the city's inhabitants, and no one forecasts a significant decrease in that percentage.

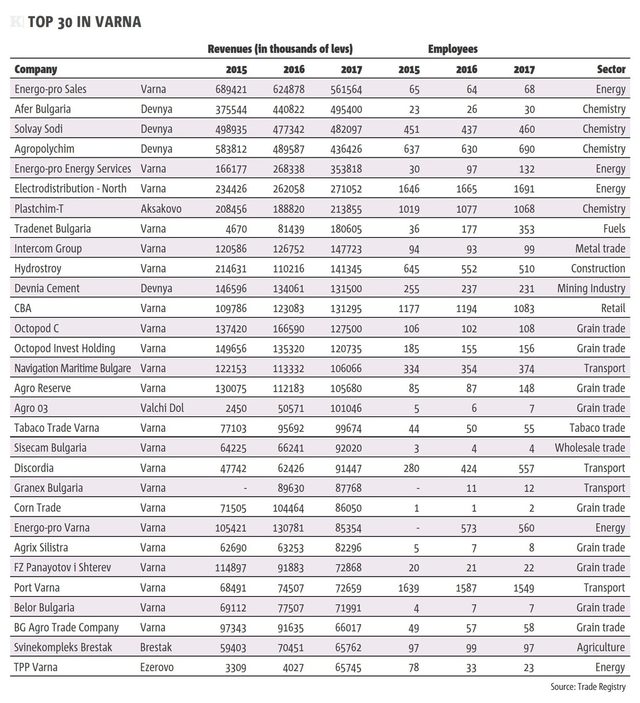

Manufacturing held the lion's share of Varna's economy in 2015 - 25%, followed by construction with 17%, and retail with 12%. This ratio is the result of the structure of the economy of the adjacent community of Devnya, of which 78% is concentrated in three manufacturing plants - Agropolychim (fertilizers), Solvay Sodi (soda ash) and Devnya Cement. All three are among the largest foreign investments in the country.

Varna's record municipal budget of 400 million levs in 2018 is the second largest after Sofia's. Its magnitude is down to the government's sudden decision to shower the city with money, "so it can catch up with Burgas", as Prime Minister Boyko Borissov stated. A subsidy from the central government in excess of 126 million levs is expected to be added to the city budget.

Over the next two years, a portion of that sum will be used to resolve Varna's infrastructure problems - removing freight traffic from the city's central zones, tackling the avalanche-like growth of traffic jams and providing sufficient parking space.

Two hubs and an island

At the beginning of December 2017, the city council gave thumbs up to the establishment of Varna Industrial and Technological Park, a joint-stock company with a capital of 2 million levs. Pursuant to the announced business plan, 50% of the company must be acquired by the state-owned National Company Industrial Zones. The city government's contribution to the company will consist of a 43 000 m² plot of land on the artificial island located between the two canals linking the sea to the Varna Lake. The plan is to build an Island Economic Zone there. If nothing else, this will be the industrial zone with the most scenic location in the country.

Earlier in 2017, Varna mayor Ivan Portnih and his peers from the adjacent towns of Aksakovo, Devnya and Beloslav signed a memorandum for the creation of Varna Innovation and Development Zone, a project company meant to develop the area around the Varna Lake.

Around the same time, the administration announced that Varna had been selected as one of the 30 digital hubs that will receive support from the European Commission. This will give Varna the opportunity to use the most advanced practices of other digital innovation centres across Europe.

Not long ago, Siemens openеd its own technological hub in Varna which will initially employ 12 engineers. They will develop and integrate robotic systems for the automotive industry.

Difficult doesn't mean impossible

Summer is the season of optimists. Sergey Petrov, who works for a tour operator in the city and organizes transfers from the airport to the coastal resorts St. Constantine and Elena and Golden Sands, is one of them.

"Varna went through an overly long 'blockade' period. That's demotivating, but it also became an excuse for those who couldn't develop their projects." Sergey believes that the lack of political will for change is at the root of Varna's stagnation. This is why he created the Youth political science association and its affiliate club. "This is a city with an internal dynamics. People come here to succeed. Some don't and they choose to leave. I don't think that's a solution. When something's missing, you should create it, not search for it elsewhere."

This is exactly what Dimitar Dimitrov and Tanya Kutova are doing. They're 32 and 22 years old, respectively. They came to Varna from Lovech about five years ago when she began her studies at the Tourism College in the city. Says Tanya: "Varna offers us more opportunities for development than the small city. We like the dynamics, we love it when new things are happening around us, and we feel fulfilled."

They're both working on small business projects. Dimitar says: "We don't believe that the key to success can be found only in Sofia. The fact is that Varna is continuously creating more opportunities for young and ambitious people. It's difficult to start your own business in Bulgaria, but difficult doesn't mean impossible!"

In the heart of Talyana, Varna's former merchant quarter, Marten Demirev is working on his project Innovator - a space for shared workspaces, for people with ideas and projects, for workshops with high-tech equipment. For parties, too.

According to Marten, "We've come a long way. Talyana is a place with a forgotten history, just like Kapana in Plovdiv some years back. Now we're hoping to rekindle that spirit too, and we believe that others, even more, creative people with a cause, will try to find their place in the region."

The big startup

All this tells us that "Bulgaria's seaside pearl" has a promising future if it succeeds in escaping the shadows of the past and surmounts the challenges of the present. And those, we must admit, are more than a few. The lack of connecting transport infrastructure able to provide quick links to the rest of Bulgaria, the lack of large new investments, the inactivity of the local government in their search for a new way for the city's development -all these challenges remain.

The other problem is typical of smaller Bulgarian coastal towns - what matters is to get through the summer season. "People's mentality here is strange," says Melanie Bankova, who's from Stara Zagora. "After I finished college, I started work as a hotel administrator. And right away, everything that people warned me about happened - delayed wages, failure to keep contractual arrangements In Varna, you have the constant feeling that you only matter until the end of the season, until the last month of summer. After that, nobody cares what happens to you." She decided to leave Varna and is now in Sofia.

In the early evenings at the beginning of June, the Largo, which is what locals call the pedestrian boulevard running from the centre of the city to the sea shore, becomes immersed in colourful chaos. Not far from Sevastopol, the quintessential meeting spot is the oriental grill a little to the side. On the way to the Sea Garden Park is the American restaurant, and right next to it - the French bistro. On its terrace, I bump into some old acquaintances - Jaqueline and Allen Beaurepaire. Some years ago, he was manager of one of the large French companies in Varna. In her spare time, Jaqueline worked as a volunteer at the local centre of Alliance Francaise. Ever since they often come back to the city as tourists.

"The city is full of squandered energy. I felt it years ago and I don't understand why pessimism here is so deeply entrenched. In contrast to most young French people, everyone we meet here has a clear, step-by-step vision of their future. We're foreigners, we come and go before we submerge in the city's problems, so we don't have any prejudices," Jacqueline explains. This is probably why they're both certain that the energy they described must be invested in, and quickly. Because it's the most valuable capital at Varna's disposal. Even more so than the sea.

Degrees by the beach

Varna universities offer a good education to foreign students, uncomplicated admission, and guaranteed job placement

Varna hosts four state-run universities: Economics, Medical, Technical, and the only Naval Academy in the country, as well as two private institutions - the Varna Free University and the University of Management. According to data published in 2017 by the Confederation of Independent Trade Unions of Bulgaria, the monthly salaries of 2060 levs paid to the professors at the Varna University of Economics (established in 1920, it was the first of its kind in Bulgaria) were the biggest in the country's higher education sector.

The abundance of educational opportunities and Varna's seaside location should prove irresistible to young people. Yet National Statistical Institute 2017 data shows that only 24% of Varna's population has earned a university degree, which is in tune with the national average. What's more, the number of students has been declining for the past two years, even though none of the four-state institutions admits to the drain. In 2017, 27 500 students attended - nearly 11%, or about 3 000 people, fewer than in 2016.

One big reason is the competition from Europe. Because of the accessibility of European universities to Bulgarian students, many colleges simply can't match the quality of foreign competition.

From the total number of students in Varna, about 24 000 are Bulgarian, which is close to 13% fewer than in 2016. However, the number of foreign students has risen. There were about 35000 of them for the same period - an 11% increase.

The tuition fees they pay for their degrees in Varna range from 1200 to 8000 levs per year. Varna appeals to students from Germany and the Scandinavian countries, as well as those from Turkey and Greece, which form the largest groups.

Those universities that responded to Capital's questions consider that there are two reasons apart from the affordable tuition fees mentioned by foreign students that lure them to Varna. One is the possibility of earning a degree that's valid across the EU, and the other is the relatively positive environment for young people and the low rents.

Over the past three years, the University of Economics in Varna had an average of 9000 students per annum. "According to data from April, about 8% of those who graduated in 2016 have pursued a career abroad, with 6% choosing Western Europe and 2.4% the U.S.," says Prof. Dr. Evgeni Stanimirov, associate dean of academics at the university. The percentage of students who started their own businesses is the same - 8.4%.

Currently, there're 250 foreign students at the university, with the largest groups coming from the Ukraine, Moldova and Russia. The institution's statistics indicate that the number of students from Armenia, India, Kazakhstan and Nigeria has increased over the past few years. The semester fee for non-EU students is 1250 euro for the bachelor's level and 1500 euro for the master's.

The majors most attractive to foreign students are Tourism, International Economic Relations, as well as (no surprise there!) those taught in a foreign language, such as International Business in English or International Tourism in Russian, explains Prof. Stanimirov.

Much like all other universities that teach engineers in Bulgaria, in the past few years the Technical University of Varna relies on a close partnership with businesses. There's a desperate shortage of engineers in the country and companies use different methods to recruit them even before graduation.

Since January the university has been working with Siemens Bulgaria on training automation and robotics specialists for the company's engineering hub, which will open in Varna at the end of September. The German company and the university have partnered for many years and Siemens actively participates in equipping the laboratories.

The newest iCard instruction lab at the faculty of electrical engineering is equipped with the latest generation of computers. This was made possible by the financial and technological support of iCard Services in cooperation with the Technical University of Varna. The lab's focus will be radiolocation and radio navigation.

With a 30 000 levs donation from Schneider Electric Bulgaria, the first university centre for dispatch and energy management in the country was created at the Technical University of Varna using equipment and software of the highest order.

The first career fair - Together in the Future - was held at the end of March last year, hosting 33 leading companies such as Solvay Sodi, Eldom Invest, Devnya Cement and Agropolychim. During the event, the companies presented internship and scholarship programs, job openings and retraining possibilities for graduates.

The university has about 5000 students, of which 160 come from Greece, Turkey, and Nigeria and attend the programs taught in English. The main interest from abroad is directed mostly at the naval and IT majors, but the university has the capability to teach other programs in English and Russian, with professors accredited in accordance with European requirements."

According to Naval Academy statistics, nearly 20% of the future graduates of the institution will be women. Majors such as Maritime Transportation Management are fully occupied by women. The academy's dean, Admiral Professor Boyan Mednikarov, believes that in many cases women are more motivated than men and they form a significant part of top students. He also thinks that the Bulgarian Navy will have a woman captain and commander of a military vessel in the not too distant future.

Admiral Mednikarov also stated that the Naval Academy in Varna is the most technologically advanced university in Bulgaria and one of the top 10 naval schools in the world. While these two statements are difficult to confirm, it is a fact that the naval school is the first in the country in terms of the number of graduates pursuing the career they majored in - 100% of them end up working in that field.

Students from 12 countries currently take courses there, with their number surpassing 300 this year. The largest group comes from Greece. Another project nearing completion is the training of 40 individuals who will be employed in the newly created Angolan fishing fleet. The annual tuition fees for foreign students at the Naval Academy range between 1750 and 3000 euro per semester, depending on the major, the teaching method, and the degree pursued. Tuition fees for Bulgarian students are considerably lower, standing at between 460 and 1100 levs.

The Varna Medical University teaches the largest number of foreign students in the city. Over 1700 students from 44 countries now attend courses taught in English, out of a total of 5000 divided between medical and dentistry students.

According to the university's dean Professor Dr. Krasimir Ivanov, most of the students come from EU countries. "More than half of our foreign students are from Germany, but the number of those from Great Britain, the Scandinavian countries, Spain, Italy, Belgium and Austria is also growing. We also have students from non-EU countries such as Russia, the U.S., Canada, and even Australia, India, Japan, and the United Arab Emirates."

"If I had to wait for admission in Germany, I would've waited at least twelve semesters. And the dental medicine department in Varna is new and much better equipped than the average one in Germany," says Lena Bogena, quoted by Germany's Dental Magazin.

Bogena also believes that the city offers many other advantages - living expenses are low, the average rent for a small apartment is 160 euro, in contrast to the situation in Germany the student groups are small and that allows for closer interaction with instructors, and the beach is just a ten-minute walk from the campus.

The tuition fee for the international dentistry program is 8000 euro per year. The university is also attractive because admission isn't based on diploma grades, but on the results of an entry exam and a language test instead.

The Varna Medical University holds the highest level of recognition from the European Foundation for Quality Management. The master in medical science diploma is automatically recognized by all European countries.

An enquiry about the number of Bulgarian students applying at the university in the past few years has revealed that it is also on the rise in spite of the relatively low wages in the country's healthcare sector. The reason is probably no different to that cited by foreign students - the diploma allows them to work anywhere in Europe. Little Devnya's big industry

Abundant natural resources and a seaport make the town an ideal site for manufacturingBy Iglika Filipova

- Belgium's Ecophos operates two subsidiaries in the town - phosphates producer Aliphos Bulgaria and phosphate technology development centre Technophos

- Devnya Cement sells mainly to the Bulgarian market but the adjacent seaport allows for exports

Devnya is probably the town with the highest ratio of business per capita in Bulgaria. The town of 8,000 inhabitants is home to three of the 100 largest companies in the country with more than half its workforce employed in manufacturing. The main reason is that manufacturing industries, and especially chemical plants, proliferate, most built during the Communist era and successfully privatized in the 1990s. New but smaller ventures have emerged over the years, yet the town sitting in a valley some 30 km west of Varna seems mostly to attract the chemical industry.

The formula is simple. The region is rich in different minerals, hence the plants were built there decades ago. The missing element is a highway running all the way from Varna to Sofia. Even though a stretch of the Hemus highway starting in Varna runs by Devnya, it doesn't reach Sofia, nor will it any time soon.

1. Solvay Sodi - European soda ash leader

The sale of the soda ash plant in Devnya was the first large privatization deal in the town. In 1997, Belgian group Solvay purchased 75% of the company, while the remaining 25% went to Turkey's Sisecam. Currently, Solvay Sodi is the largest producer of synthetic soda ash in Europe, with a yearly capacity of 1.5 million tons. The product, a main ingredient in the glass-making industry, is also used in the production of detergents, the chemical industry and metallurgy. The plant also produces sodium bicarbonate (baking soda) for the animal feed market and cleaning of flue gases.

Over 90% of the output is exported to markets worldwide. In Bulgaria, the plant supplies its products to Sisecam's glass factory in Targovishte.

"In 2017 our production ran at full capacity and we broke records in our worldwide sales," said the managing director of Solvay Sodi Spiros Nomikos. The company has received investments to the tune of 1.5 billion levs since it was privatized 20 years ago.

2. Agropolychim - from bankruptcy to peak sales

Devnya-based fertilizer manufacturer Agropolychim was also privatized successfully by Acid&Fertilizers in 1999, in spite of being virtually bankrupt at the time. Last year, the company reported a record sales volume of 853,000 tons. The consolidated sales include the results of its trading subsidiary Afer Bulgaria which sells imported fertilizers in addition to its own products. The sales of imported fertilizers also marked a record volume of 1.34 million tons, a 12% yearly raise.

The company predominantly works for local and regional markets (central and eastern Europe) - the destination of 70% of its output - as well as the Middle East, North and South America.

During the past seven years, Agropolychim has invested almost 230 million levs, and a further 250 million levs is planned for the next five years. The projects include the construction of a terminal for cereals processing, which will be a first for the company.

3. Aliphos - the phosphate specialist

The manufacturer of phosphates for the feed industry Aliphos Bulgaria (formerly Dekaphos) is located on Agropolychim's premises. The company was created in 2002 as a joint venture between Agropolychim and Belgium's Ecophos. Six years later it became the property of the Belgian investor. Apart from their shared history and location, the two companies are presently connected by a business partnership. "We used to import our raw materials, but since we're a small company, the imports were expensive and difficult. Two years ago, we started buying phosphoric acid from Agropolychim, and with one additional step to our process, we purify the material and make it suitable for feeding purposes," said the company's executive director Denitsa Zhelyazkova.

In the past few years, the company has worked exclusively for exports. In 2013 Ecophos purchased Dutch company Aliphos (this is when the Bulgarian company changed its name) and Aliphos Bulgaria started producing for its clients, mainly in Algeria. "This led to the loss of the Bulgarian market but 100% of our output is exported," added Zhelyazkova. The company currently employs 65 people.

Two years ago, through another subsidiary - Technophos, the Belgian owner built a technology and innovation centre at a different location in Devnya. The 10-million-euro laboratory for conducting phosphate research is equipped with all modules for the manufacture of different products (dicalcium phosphate, phosphoric acid, phosphogypsum, hydrochloric acid) and it can present solutions to different challenges to its parent company or to clients. One of the solutions on offer provides for the extraction of phosphorus from low-content ore - a process patented by Ecophos' founder Mohamed Takhim. Technophos is currently working on several projects for its parent company as well as for several clients in Jordan, China, and Brazil. In addition, there's focus on developing a method for phosphoric acid purification according to the latest environmental regulations. The team consists of 38 people, 60% of whom are engineers.

4. Devnya Cement - not everything is about chemistry

On the other side of the highway, in Devnya's northern industrial zone, is another great example of a company that has survived and developed its production capabilities after the transition to the market economy -Devnya Cement. The cement plant now has a second successful owner since its initial privatization in 1998 by Italcementi Group. Two years ago, the Italian group sold the plant to Germany's HeidelbergCement. Shortly before the deal, the plant underwent a complete reconstruction worth about 330 million levs in which the six old furnaces were replaced by a single modern facility of equal capacity. The installation allows for the use of refuse-derived fuels.

"This has a positive effect on our carbon imprint and reduces the quantity of waste delivered to the municipal dumps," commented the managing director of Devnya Cement, Axel Konrads.

The company sells most of its output domestically and exports part of it. "One of the great advantages of the Devnya region is that we're near a port facility. This really facilitates international trade," explained Konrads.

He believes there's another reason for the concentration of manufacturing industries in the area. "Devnya predominantly hosts industries that use raw materials, and here we have many sources of very clean materials for different production processes, including cement. Devnya Cement has a shared limestone quarry with Solvay Sodi. We use the fine grind and they - the coarse. The cement factory has a marl quarry nearby. This makes production economically viable since we don't have to transport raw materials over long distances," said Konrads.

About 90% of the raw materials used by the cement plant are mined in the Devnya area.

Varna, Bulgaria's third-largest city, displays a peculiar mix of charm and difficult character. It functions on overdrive in summer, then hibernates until the next. Its most valuable asset is the sea, yet it enviously looks west toward the capital. It resents its reputation of being a "captive" to powerful local business groups but it never manages to properly highlight its successes. The "summer capital of Bulgaria" tag is insipid, but Varna believes it confidently. Not only because its history spans far beyond the Bulgarian state, or because it used to be a meeting point for merchants from Genoa and Dubrovnik, but because today it has reasons to be optimistic.

Its seven universities and 28 000 students imbue it with youthfulness and energy. Tourism brings cosmopolitan city dynamics. Even though it lost the race for the title "European Capital of Culture 2019" (a city in the EU designated to host a series of cultural events with pan-European dimension), it still boasts a cultural life that few other Bulgarian cities can match: the oldest music festival in Bulgaria called Varna Summer, the world's only international ballet competition, the International Graphics Biennial, its film and theatre festivals, and last year - even the MTV Varna Beach party. Тhe city's economy is growing, unemployment is falling, and its population increases every year. This is how Varna's "tarnished image" - the feeling among the locals that their city is trailing behind its peers, turns out to be more of a PR and management issue.